In the distant recesses of Earth’s history, long before humans walked the planet, magnificent avian giants dominated ecosystems across multiple continents. These weren’t just slightly larger versions of today’s birds—they were colossal creatures that pushed the boundaries of flight physics or abandoned the skies altogether to become apex predators on land. From the enormous Argentavis that sailed ancient skies with wingspans comparable to small aircraft, to the terrifying terror birds that hunted across prehistoric South America, these feathered titans represent fascinating evolutionary experiments. Their stories reveal how birds once claimed ecological niches now dominated by mammals, challenging our perception of these animals as necessarily small or delicate creatures. The legacy of these magnificent birds offers a window into lost worlds and evolutionary pathways that once flourished before disappearing into the fossil record.

The Age of Avian Giants: Setting the Timeline

Giant birds have appeared multiple times throughout Earth’s history, thriving particularly after the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago. This mass extinction event cleared ecological niches that allowed birds to diversify dramatically and, in some cases, achieve extraordinary sizes. The Paleocene and Eocene epochs (66-33.9 million years ago) saw the rise of early giant flightless birds like Gastornis in Europe and North America. Later, during the Oligocene and Miocene (33.9-5.3 million years ago), South America became home to the terrifying phorusrhacids or “terror birds,” while the skies of Argentina witnessed the flight of Argentavis magnificens, potentially the largest flying bird ever. The most recent giants—the elephant birds of Madagascar and moas of New Zealand—survived until just a few hundred years ago, making them almost contemporaries with modern human civilization and demonstrating that giant birds were not merely a phenomenon of deep time.

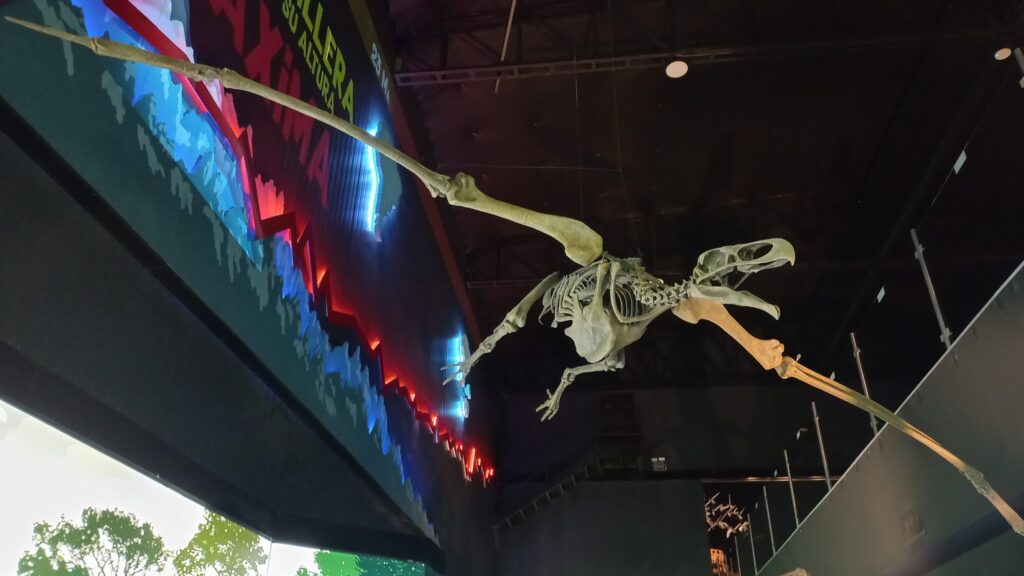

Argentavis: The Largest Flying Bird in History

Soaring above the landscape of prehistoric Argentina approximately 6 million years ago, Argentavis magnificens stands as potentially the largest flying bird ever to have existed. With an estimated wingspan reaching 5.5 to 7 meters (18-23 feet)—comparable to a small aircraft—and weighing approximately 70-72 kilograms (154-158 pounds), this colossal bird pushed the very limits of flight physics. Belonging to the extinct family Teratornithidae (related to New World vultures), Argentavis likely employed primarily soaring flight, using thermal updrafts to remain aloft with minimal energy expenditure. Paleontologists believe its massive size would have made flapping flight extremely energy-intensive, suggesting it probably launched itself from elevated positions and relied on favorable air currents. Its enormous size and predatory nature likely made Argentavis an apex predator in its ecosystem, capable of consuming medium-sized mammals and other substantial prey that would be unmanageable for most modern birds of prey.

The Terrifying Phorusrhacids: South America’s Terror Birds

Among the most formidable predators to ever walk Earth’s surface were the phorusrhacids, colloquially known as “terror birds,” which dominated South American ecosystems for over 60 million years after the dinosaurs’ extinction. These flightless carnivores stood up to 3 meters (10 feet) tall with massive, axe-like beaks capable of delivering bone-crushing blows to prey. Unlike modern flightless birds like ostriches, terror birds evolved specifically as predators, with powerful legs allowing them to reach speeds of up to 50 km/h (31 mph) when pursuing prey. The largest species, Kelenken guillermoi, possessed the largest bird skull ever discovered—nearly 71 cm (28 inches) long—featuring a hooked beak designed for tearing flesh. What makes these birds particularly fascinating is their role as apex predators in a mammal-dominated world, essentially filling ecological niches typically occupied by large carnivorous mammals on other continents, demonstrating a remarkable case of convergent evolution where birds evolved to become the ecological equivalents of big cats or wolves.

Gastornis: The European Giant Once Mistaken for a Predator

For decades after its discovery in the 1850s, Gastornis (formerly called Diatryma) was portrayed as a fearsome predator stalking the forests of early Eocene Europe and North America approximately 56-45 million years ago. Standing up to 2 meters (6.6 feet) tall with a massive head and powerful beak, this flightless bird certainly looked intimidating in reconstructions. However, modern research has dramatically revised our understanding of this giant bird’s lifestyle. Isotope analysis of its fossilized bones, studies of its beak structure, and the absence of predatory adaptations in its feet strongly suggest Gastornis was actually a herbivore, possibly specializing in cracking tough nuts, seeds, and fruits with its powerful jaw apparatus. This scientific reinterpretation demonstrates how our understanding of prehistoric creatures continues to evolve with new evidence and analytical techniques. Gastornis now represents an important example of how birds expanded into large-bodied herbivore niches during the early Cenozoic era, a period when mammals were still relatively small and had not yet diversified into the dominant large herbivores they would later become.

Elephant Birds: Madagascar’s Avian Colossi

The elephant birds of Madagascar represent some of the most massive birds ever to have existed, with the largest species, Vorombe titan, weighing an estimated 650 kg (1,430 lbs) and standing over 3 meters (10 feet) tall. These enormous ratites—relatives of ostriches, emus, and kiwis—thrived on the island of Madagascar until their relatively recent extinction approximately 1,000-500 years ago, making them among the last giant bird species to disappear from Earth. Their massive eggs, with volumes exceeding 11 liters, remain the largest single cells ever known to exist. Archaeological evidence suggests these birds coexisted with human settlers for centuries before their ultimate extinction, with their enormous eggs serving as valuable resources—a single elephant bird egg could provide nourishment equivalent to approximately 150 chicken eggs. The relatively recent disappearance of these birds gives scientists unprecedented insights into their biology through well-preserved subfossil remains and even intact eggshells, some of which still contain ancient DNA that helps reconstruct their evolutionary relationships to other birds. The elephant birds stand as a sobering example of how even the most impressive animals can be vulnerable to extinction through human hunting and habitat modification.

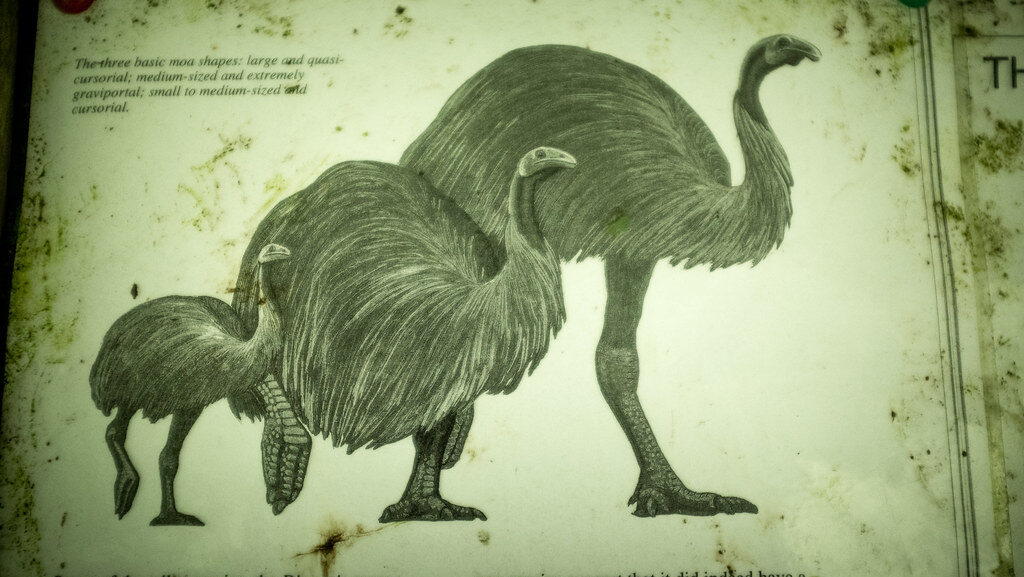

The Mighty Moas of New Zealand

New Zealand’s isolated archipelago once harbored nine species of massive flightless birds known as moas, with the largest, Dinornis robustus, standing over 3.6 meters (12 feet) tall with its neck extended. These impressive herbivores evolved in the absence of mammalian predators, developing into the dominant large herbivores of New Zealand’s diverse ecosystems. Unlike many other large flightless birds, moas completely lost all traces of wings, not even retaining vestigial wing bones, representing one of the most extreme cases of flight loss in avian evolution. Their diverse beaks and feeding adaptations allowed different moa species to occupy various ecological niches, from forest browsers to grassland grazers, demonstrating remarkable adaptive radiation. The moas’ extinction came swiftly after human arrival to New Zealand around 1300 CE, with archaeological evidence suggesting they were hunted to extinction within just 100 years—one of the fastest documented extinctions of a megafauna group and a sobering reminder of humans’ capacity to rapidly transform ecosystems.

Dromornis: Australia’s “Thunder Birds”

Australia contributed its own chapter to the story of giant birds with the dromornithids, often called “thunder birds” or “demon ducks of doom,” which thrived from about 25 million to 50,000 years ago. The largest, Dromornis stirtoni, stood approximately 3 meters (10 feet) tall and weighed up to 500 kg (1,100 lbs), making it among the heaviest birds ever known. These massive birds were initially thought to be fearsome predators, but careful analysis of their skull morphology and beak structure revealed they were likely specialized herbivores with massive gastrointestinal systems capable of processing tough plant material. Unlike many giant flightless birds that evolved from flying ancestors relatively recently, the dromornithids represent an ancient lineage that diverged early in avian evolution, possibly sharing ancestry with modern waterfowl like ducks and geese despite their radically different appearance. Their gradual extinction coincided with Australia’s increasing aridity and changing vegetation patterns over millions of years, with the final species disappearing shortly after human arrival on the continent—a pattern that would repeat with other giant birds worldwide.

Pelagornis: The Bird with the Longest Wingspan

While Argentavis often receives attention for its massive bulk, Pelagornis sandersi may claim the title for the largest wingspan of any bird that ever lived, with estimates ranging from 6.1 to 7.4 meters (20-24 feet) tip to tip. This enormous seabird soared above Earth’s oceans between 25 and 28 million years ago during the late Oligocene epoch, using its remarkable wingspan to glide efficiently on ocean winds for potentially thousands of kilometers without landing. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Pelagornis was its extraordinary beak, lined with bony, tooth-like projections that were actually extensions of its jawbone rather than true teeth, creating a highly effective fish-trapping apparatus. Despite its enormous wingspan, the bird’s hollow bones and lightweight structure kept its weight between just 22-40 kg (48-88 lbs), demonstrating remarkable evolutionary adaptations for efficient flight. Paleontologists believe Pelagornis represents an extreme example of adaptive specialization for oceanic soaring, with a body plan so perfected for this lifestyle that nothing comparable exists among modern birds, showing how evolution has explored flight designs beyond what we observe in contemporary species.

Brontornis: The “Thunder Bird” of South America

Among South America’s diverse assemblage of giant birds, Brontornis burmeisteri stands out as one of the most massive, estimated to have weighed between 350-400 kg (770-880 lbs) and standing around 2.8 meters (9.2 feet) tall. This enormous flightless bird lived approximately 23-11 million years ago during the Miocene epoch in what is now Argentina, alongside the terror birds but belonging to a different avian lineage. Traditionally classified as a phorusrhacid (terror bird), recent research suggests Brontornis may actually represent a massive flightless member of the group Anseriformes, making it more closely related to ducks and geese than to carnivorous birds. Its massive beak and robust build have created considerable debate among paleontologists regarding its diet, with some evidence suggesting it may have been an omnivore capable of consuming both plant material and small animals. The very name “Brontornis” means “thunder bird,” reflecting both its massive size and the substantial impact its footsteps would have made as it moved across the prehistoric Patagonian landscape, creating a striking image of this colossal bird that once dominated South American ecosystems.

The Physics of Giant Bird Flight

The enormous flying birds of prehistory present fascinating questions about the upper limits of avian flight. As body mass increases, the wing area must increase disproportionately to generate sufficient lift, creating a theoretical ceiling for flying bird size. Birds like Argentavis and Pelagornis approached this ceiling by developing specialized flight strategies—primarily static soaring that exploited thermal updrafts and air currents rather than relying on energetically costly flapping flight. Computer modeling suggests these giants likely launched from elevated positions or took advantage of headwinds for takeoff, similar to how large modern birds like albatrosses require running starts or favorable winds to become airborne. Their wing morphology typically featured high aspect ratios (long, narrow wings) that maximized gliding efficiency while minimizing energy expenditure. Hollow pneumatic bones, efficient respiratory systems with air sacs, and other weight-reducing adaptations allowed these birds to achieve sizes that seem almost impossible by modern standards, demonstrating how evolution pushed the very boundaries of flight physics. The fact that we don’t see birds of comparable size today suggests these giants may have occupied specialized ecological niches that no longer exist or required specific atmospheric conditions that prevailed during their evolutionary history.

Evolutionary Pathways to Gigantism

The repeated evolution of giant birds across different lineages and time periods demonstrates a fascinating pattern of convergent evolution toward large body size. In many cases, island environments proved particularly conducive to avian gigantism—as seen with elephant birds in Madagascar and moas in New Zealand—where the absence of mammalian predators removed selection pressure for flight while allowing birds to occupy ecological niches typically filled by large mammals elsewhere. This phenomenon, known as island gigantism, allowed birds to evolve larger sizes free from many constraints. Meanwhile, continental giants like terror birds evolved following the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, exploiting vacant predator niches during periods when mammals had not yet evolved into large-bodied forms. From a physiological perspective, the avian respiratory system—with efficient unidirectional airflow through air sacs—provided crucial advantages for supporting large body sizes by ensuring high oxygen delivery even as metabolic demands increased with size. Interestingly, gigantism evolved independently in multiple bird lineages rather than being concentrated in one group, suggesting that the avian body plan possesses inherent versatility that allowed different bird groups to explore large-bodied ecological niches when opportunities arose.

The Extinction of Avian Giants

The disappearance of giant birds from Earth’s ecosystems occurred through different mechanisms across various time periods, revealing a complex pattern of extinction drivers. Many of the earlier giants, like Gastornis and some terror birds, disappeared during natural climate shifts and ecosystem reorganizations millions of years ago as mammals diversified into competing ecological niches. The more recent disappearances of island giants like elephant birds and moas correlate strongly with human arrival on their respective islands, with archaeological evidence pointing to hunting pressure and habitat modification as primary extinction drivers. These human-caused extinctions occurred with remarkable speed—New Zealand’s moas disappeared within a century of human settlement, despite having survived for millions of years previously. Analysis of ancient DNA and radiocarbon dating has allowed scientists to track these extinction timelines with increasing precision, revealing that many giant birds were resilient through substantial climate changes only to succumb quickly to human pressures. This pattern suggests that while giant birds faced inherent vulnerabilities due to their typically slow reproduction rates and specialized ecological requirements, it was the introduction of novel predators—humans—that ultimately proved insurmountable for the most recent giants, offering cautionary lessons about human impacts on specialized island fauna.

Legacy and Lessons from the Age of Giant Birds

The story of Earth’s giant birds offers profound insights into evolutionary processes and extinction dynamics that remain relevant today. These avian giants demonstrate how evolution can produce remarkable specializations when ecological opportunities arise, pushing the boundaries of body size and adapting bird anatomy for roles we might typically associate with mammals. The relatively recent extinction of birds like elephant birds and moas—close enough to the present that their DNA can still be extracted and analyzed—provides exceptional opportunities to study extinction processes in detail. Contemporary conservation efforts benefit from understanding how these magnificent birds disappeared, particularly as similar pressures threaten large-bodied birds today, from albatrosses to large ratites like cassowaries. Some scientists have even explored the possibility of using genetic engineering to “resurrect” traits of extinct giant birds in their living relatives—not to recreate extinct species wholesale, but to understand the genetic basis of their unique adaptations. Perhaps most importantly, the giant birds remind us that Earth’s biodiversity has experienced profound changes even in geologically recent times, and that the avian diversity we observe today represents just one moment in a long evolutionary story that once included feathered giants ruling both land and sky.

Conclusion

The saga of giant birds represents one of evolution’s most fascinating chapters—a time when avian species achieved sizes that seem almost mythological by today’s standards. From the soaring Pelagornis with its record-breaking wingspan to the formidable terror birds that stalked ancient landscapes, these feathered giants pushed the boundaries of what birds could become. Their stories reveal evolution’s remarkable versatility, showing how the basic avian body plan could be modified to fill ecological roles now dominated by mammals. While these magnificent birds have disappeared, leaving only fossil traces and occasionally DNA fragments, their legacy continues through scientific discovery and in the modern birds that represent their distant relatives. As we face contemporary biodiversity challenges, the rise and fall of avian giants offers valuable lessons about evolution, extinction, an