Most of us have marveled at the epic journeys birds undertake during migration – traversing continents and crossing vast oceans with seemingly tireless wings. But what if I told you that some of these magnificent travelers are making strategic pit stops at backyard bird feeders across North America? This fascinating adaptation represents an evolutionary pivot as birds adjust to human-altered landscapes. The ruby-throated hummingbird, in particular, has become adept at incorporating our backyard offerings into its migration strategy, creating a unique relationship between wild migratory birds and human hospitality. This relationship not only helps these tiny travelers complete their incredible journeys but also connects us directly to one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena.

The Evolutionary Marvel of Bird Migration

Bird migration stands as one of nature’s most impressive phenomena, with some species traveling thousands of miles biannually between breeding and wintering grounds. These journeys push birds to their physiological limits, requiring precise timing, navigation skills, and enormous energy reserves. Migration evolved over thousands of years as birds adapted to seasonal food availability and breeding conditions. Before human development altered landscapes, birds relied entirely on natural food sources like insects, seeds, and nectar from wild plants to fuel their journeys. This evolutionary marvel represents countless generations of birds refining their routes and strategies to maximize survival in a challenging and unpredictable world.

Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds: The Tiny Titans of Migration

The ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) weighs less than a nickel but completes one of the most remarkable migrations in the bird world. These diminutive fliers travel up to 2,000 miles between Central America and the eastern United States and Canada each year. Most astonishingly, many cross the Gulf of Mexico in a single 500-mile non-stop flight that takes approximately 20 hours of continuous flying. To accomplish this feat, ruby-throats double their body weight before departure, converting the extra mass to fuel for their journey. Their heart rate can exceed 1,200 beats per minute during migration, and they beat their wings about 53 times per second, demonstrating the extraordinary physiological adaptations that make their migration possible.

The Energetic Demands of Long-Distance Flight

The energy requirements for migratory birds are staggering and represent one of the most challenging aspects of their annual journeys. Birds must accumulate sufficient fat reserves before departure, as fat provides the most efficient energy storage, delivering about twice the energy per gram compared to proteins or carbohydrates. During peak migration, a small songbird might burn through 1-4% of its body weight per hour of flight. This metabolic miracle is made possible by numerous adaptations, including increased red blood cell production to transport oxygen more efficiently, enlarged flight muscles, and the ability to metabolize fat reserves rapidly. The combined effect of these adaptations allows birds to perform feats of endurance that would be impossible for other animals of similar size.

The Rise of Backyard Bird Feeding

Bird feeding has evolved from occasional winter charity to a year-round cultural phenomenon that significantly impacts wild bird populations. In North America alone, more than 59 million households provide food for wild birds, creating a supplemental feeding network that spans the continent. Americans spend over $4 billion annually on bird seed and related equipment, demonstrating the cultural significance of this activity. The practice began gaining widespread popularity in the early 20th century, coinciding with increased urbanization and a growing disconnect from nature. What started as occasional winter feeding has transformed into sophisticated feeding stations offering specialized foods for different species year-round, creating reliable refueling opportunities for migrating birds that simply didn’t exist a century ago.

Adapting to Human-Altered Landscapes

Birds demonstrate remarkable behavioral plasticity, adjusting their strategies to take advantage of new resources in human-modified environments. Research has documented numerous species altering migration patterns, timing, and even routes in response to reliable food sources provided by humans. Some populations have shifted from complete migration to partial migration, with portions of the population remaining year-round near dependable food sources. Urban areas now offer both challenges and opportunities for migrants, with artificial light pollution disrupting navigation but concentrated food resources providing reliable energy. This adaptability represents a form of cultural evolution among bird species, with knowledge of artificial feeding opportunities potentially passed between generations through learning rather than genetic inheritance.

Hummingbird Feeders: Artificial Nectar Stations

Hummingbird feeders have become particularly significant in supporting migration, offering high-energy sugar water that mimics natural nectar sources. A properly maintained feeder provides a concentrated energy source that allows hummingbirds to efficiently replenish their reserves, sometimes doubling their weight in just two days of feeding. The standard sugar solution of one part sugar to four parts water closely approximates the sugar concentration in many natural flower nectars preferred by hummingbirds. Modern feeder designs incorporate features to prevent fermentation, resist invasion by insects, and provide perches for resting hummingbirds to conserve energy while feeding. This artificial nectar network has effectively created a supplemental infrastructure supporting hummingbird migration across North America.

Tracking Migration Through Citizen Science

The relationship between migratory birds and backyard feeders has been illuminated through extensive citizen science projects that track migration patterns. Journey North, Operation RubyThroat, and eBird engage thousands of volunteers who document the first spring sightings of migratory species, creating detailed maps of migration progression. These projects have revealed how ruby-throated hummingbirds follow the blooming of native flowers northward in spring, with backyard feeders serving as supplemental resources along the way. The accumulated data show migration waves moving approximately 20 miles per day northward in spring, with birds adjusting their pace in response to weather conditions and food availability. Citizen scientists maintaining consistent feeding stations and recording observations have contributed invaluable data that would be impossible to collect through traditional research methods alone.

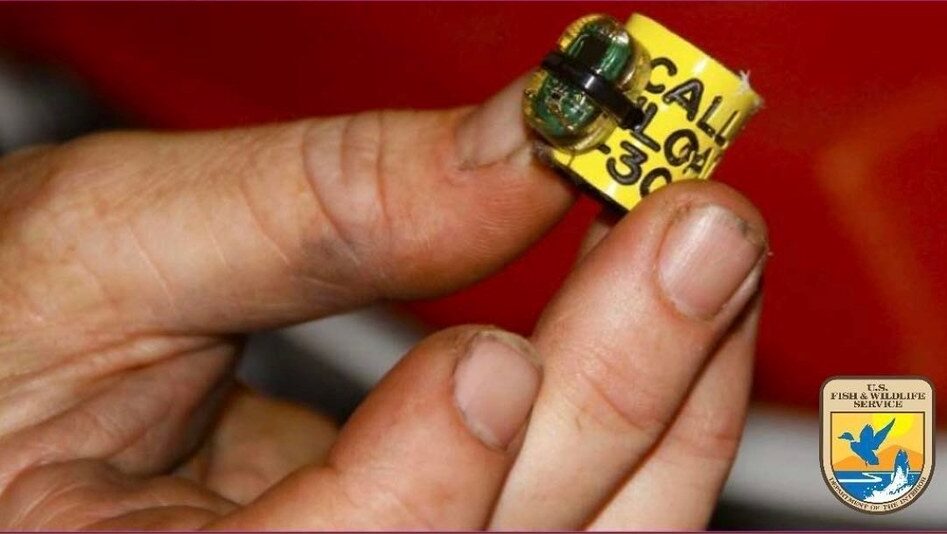

Scientific Evidence of Feeder Dependence

Research has begun documenting the extent to which migratory birds incorporate artificial feeding stations into their migration strategies. Studies using stable isotope analysis can determine what proportion of a bird’s diet comes from natural versus artificial food sources, revealing that some hummingbird populations derive up to 20% of their pre-migration energy from backyard feeders. GPS tracking of individual birds has shown that some migrants make detours of several miles to visit reliable feeding stations remembered from previous migrations. Long-term banding studies indicate that the same individual birds often return to specific feeders year after year, suggesting that these locations become incorporated into their mental maps of the migration route. This growing body of evidence confirms that human-provided food sources have become integrated into the migration ecology of numerous species.

The Timing of Feeder Maintenance

For humans hoping to support migrating birds, the timing of feeder maintenance becomes crucial, particularly during peak migration periods. Spring migration for ruby-throated hummingbirds typically begins in late February in the southern United States and continues through May as birds move northward. Fall migration spans from July through October, with most birds departing the northern breeding grounds by late September. Contrary to popular myth, maintaining feeders in fall does not prevent birds from migrating, as their departure is triggered primarily by changing day length rather than food availability. Keeping feeders filled and clean during these critical periods can provide life-saving energy to exhausted travelers, particularly during adverse weather conditions that might prevent natural foraging.

Potential Risks and Concerns

While feeders provide benefits to migrating birds, they also present potential risks that responsible bird enthusiasts should address. Poorly maintained feeders can spread diseases like avian conjunctivitis or salmonellosis when many birds congregate at a single feeding site. Sugar water in hummingbird feeders can ferment in hot weather, potentially causing fatal fungal infections if not regularly changed. Feeders placed near windows contribute to bird-window collisions, which kill hundreds of millions of birds annually in North America. Additionally, feeders can create artificial population concentrations that attract predators or alter natural behaviors. These concerns highlight the importance of responsible feeding practices, including regular cleaning, proper placement, and maintenance schedules that align with migration patterns.

Creating Bird-Friendly Stopover Habitat

While feeders provide immediate energy, creating natural habitat enhances the overall value of your yard as a migration stopover. Native flowering plants provide natural nectar sources while supporting the insect populations that form a crucial protein component of many birds’ diets. Layered vegetation with trees, shrubs, and ground cover offers shelter, nesting sites, and protection from predators during vulnerable refueling periods. Water features with moving water attract migrants and provide essential bathing opportunities to maintain feather condition during long journeys. Avoiding pesticides preserves the insect food base that many migrants depend on for the protein necessary to rebuild muscle after long flights. This holistic approach to habitat creation complements feeding efforts and contributes to conservation beyond the immediate benefits of feeders.

The Future of Bird-Human Relationships

The integration of backyard feeders into migration strategies represents an evolving relationship between humans and wild birds in the Anthropocene era. As climate change alters traditional migration timing and habitat availability, the supplemental food network provided by humans may become increasingly important for some species’ survival. Research suggests that feeding stations may help some birds adapt to shifting seasonal patterns by providing reliable resources when natural food availability becomes less predictable. Conversely, artificial feeding could potentially mask the ecological signals that would otherwise drive evolutionary adaptation to changing conditions. This complex relationship highlights how humans have become embedded in ecological systems, creating both opportunities and responsibilities for conservation in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the phenomenon of migratory birds incorporating backyard feeders into their epic journeys represents a fascinating intersection of wild nature and human influence. For the ruby-throated hummingbird and other species, our offerings of sugar water and seeds have become integrated into their survival strategies, creating a continental network of refueling stations that supplement natural resources. This relationship connects us directly to one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena while reminding us of our capacity to positively impact wildlife. As we continue to alter landscapes and climates, maintaining this supportive relationship through responsible feeding and habitat creation may become increasingly important for preserving the miracle of bird migration for future generations to witness and enjoy.