The majestic silhouettes of birds of prey soaring across the sky have captivated human imagination for millennia. However, many of these magnificent raptors—from the Philippine Eagle to the Madagascar Fish Eagle—now teeter on the brink of extinction. These apex predators that once ruled the skies face unprecedented challenges in the modern world. Their rapid decline represents not just the loss of iconic species but signals deeper environmental disturbances that threaten entire ecosystems. Understanding why these rare raptors are vanishing at alarming rates is crucial not only for conservation efforts but for comprehending the broader implications of our changing planet.

The Current State of Raptor Conservation

Of the approximately 557 raptor species worldwide, nearly 20% are currently threatened with extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Species like the California Condor, once reduced to just 22 individuals in the wild, exemplify the precipitous decline these birds have experienced. The situation is particularly dire for island-endemic raptors, with over 60% facing high extinction risk compared to 23% of continental species. Even formerly abundant species like certain kestrels and kites have seen population reductions of 50-80% in recent decades, placing them among the fastest-declining bird groups globally. These statistics paint a troubling picture of biodiversity loss that extends beyond individual species to affect entire ecological networks dependent on these top predators.

Habitat Loss: The Primary Threat

Deforestation represents the single greatest threat to raptor populations worldwide, with an estimated 18.7 million acres of forest lost annually. For forest specialists like the Harpy Eagle in the Amazon or the Philippine Eagle in Southeast Asia, the destruction of old-growth forests eliminates irreplaceable nesting sites and hunting territories. Wetland drainage particularly affects marsh-dependent species like the Madagascar Fish Eagle, which has lost over 60% of its habitat in recent decades. Agricultural expansion in particular has transformed landscapes once dominated by natural vegetation into monocultures unsuitable for most raptors. The fragmentation of remaining habitat creates isolated population pockets, reducing genetic diversity and making these birds more vulnerable to local extinction events through inbreeding depression and diminished adaptive capacity.

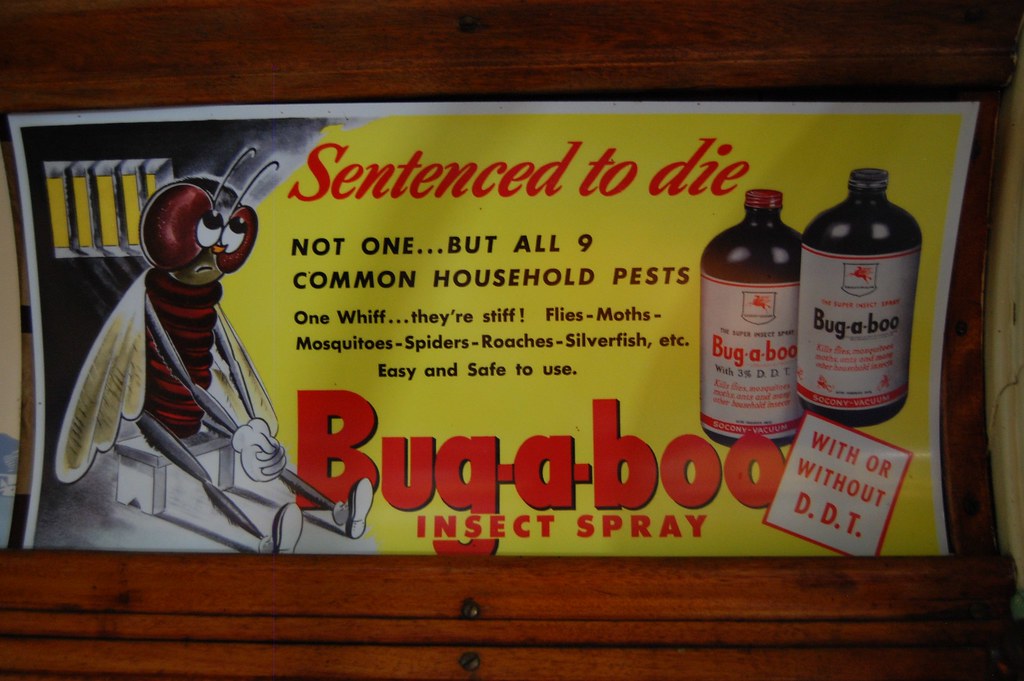

The Insidious Impact of Pesticides

Chemical contaminants continue to pose existential threats to raptors globally, decades after the DDT crisis that nearly wiped out Peregrine Falcons and Bald Eagles in North America. Modern pesticides like neonicotinoids and rodenticides move through food chains, becoming concentrated in top predators through bioaccumulation. Research has documented detectable levels of agricultural chemicals in 87% of raptor tissue samples across multiple continents, with particularly high concentrations in agricultural landscape specialists. These toxins affect reproduction by thinning eggshells, reducing fertility, and causing developmental abnormalities in chicks. Secondary poisoning occurs when raptors consume prey that has ingested rodenticides, creating a particularly insidious threat for species that specialize in controlling rodent populations.

Climate Change Effects on Raptor Populations

Rising global temperatures have begun disrupting the delicate timing of raptor breeding cycles relative to prey availability. Species like the Gyrfalcon of the Arctic face habitat contraction as their specialized cold-weather adaptations become disadvantageous in warming environments. Increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events directly impact nesting success, with studies documenting complete breeding failure in some raptor populations following unseasonable storms. Migration patterns are shifting unpredictably, forcing birds to travel farther for resources or abandon traditional routes entirely. The resulting phenological mismatches—where predators and their prey are no longer synchronized in their life cycles—create cascading effects throughout food webs that may prove impossible for specialized predators to overcome.

Direct Persecution: An Ongoing Challenge

Despite legal protections in many countries, direct killing remains a significant mortality factor for numerous raptor species. In Mediterranean migration routes alone, an estimated 25 million birds of prey are illegally shot or trapped annually according to BirdLife International. Cultural beliefs in some regions perpetuate the targeting of owls and other nocturnal raptors associated with superstition or folk medicine. Shooting and poisoning campaigns by livestock owners specifically target large eagles and vultures perceived as threats to domestic animals, despite research showing actual predation rates are typically minimal. In Southeast Asia, demand for traditional medicine and taxidermy specimens fuels ongoing poaching of critically endangered species like the Javan Hawk-Eagle, with prices for a single bird reaching thousands of dollars on black markets.

The Special Vulnerability of Island Endemics

Island-dwelling raptors face disproportionate extinction risk due to their naturally restricted ranges and specialized adaptations. The Critically Endangered Ridgway’s Hawk of Hispaniola demonstrates this vulnerability, having disappeared from 98% of its historical range. Invasive species introduce novel threats that island raptors have no evolutionary defense against, such as the parasitic fly that nearly exterminated the Ridgway’s Hawk by infesting nestlings. Limited genetic diversity in island populations reduces their ability to adapt to changing conditions or resist disease outbreaks. The combination of these factors explains why island raptors like the Madagascar Serpent Eagle and Mauritius Kestrel have proven especially susceptible to human-induced environmental changes, with recovery efforts requiring intensive intervention to prevent extinction.

Collision Hazards in the Modern Landscape

Anthropogenic structures present deadly obstacles for raptors adapted to navigate natural landscapes. Power lines alone kill an estimated 12-64 million birds annually in the United States, with large-winged species like eagles and vultures particularly susceptible to electrocution. Wind turbines pose a significant threat to migratory raptors, with certain poorly-sited facilities documenting hundreds of raptor fatalities yearly. Vehicle collisions claim countless lives as raptors hunt along roadways or scavenge roadkill, particularly affecting opportunistic species like Red-tailed Hawks. Even communication towers and skyscrapers with reflective glass surfaces become deadly barriers during migration, with nocturnal migrants like owls facing additional risks from light pollution that disrupts navigation and alters hunting behavior.

The Vulture Crisis: A Conservation Emergency

Old World vultures face what conservationists have termed a full-blown crisis, with population declines exceeding 90% for several species across Africa and Asia. The primary culprit has been identified as diclofenac and related veterinary drugs used in livestock that cause fatal kidney failure in vultures feeding on treated carcasses. This catastrophic decline has occurred with stunning rapidity—the Indian White-backed Vulture population crashed from millions to near-extinction in just two decades. The ecological consequences have been severe, with rotting carcasses remaining unscavenged and consequently increasing the spread of diseases like rabies and anthrax. The economic impact is equally significant, with studies estimating the loss of vulture ecosystem services costs millions annually in increased disease burden and waste management requirements.

The Plight of the Philippine Eagle

The Philippine Eagle exemplifies the complex challenges facing the world’s rarest raptors, with fewer than 400 breeding pairs remaining in the wild. Each pair requires 25-50 square miles of undisturbed forest to sustain itself, yet the Philippines has lost over 75% of its original forest cover. Their extremely low reproductive rate—producing just one chick every two years—makes population recovery painfully slow even under ideal conditions. Cultural significance as the national bird has not translated into sufficient habitat protection, with illegal logging continuing even in designated conservation areas. The species also faces the added threat of being shot by hunters who either mistake them for common prey birds or specifically target them as trophies, with several captive-bred released birds having been shot within months of reintroduction.

Conservation Success Stories

Despite the grim outlook for many species, conservation interventions have achieved remarkable successes for certain raptors. The Peregrine Falcon’s recovery from fewer than 400 pairs in the 1970s to over 3,000 pairs today stands as a testament to what targeted conservation can achieve when addressing specific threats like DDT. Captive breeding programs have proven crucial for species like the California Condor, which has increased from 22 individuals to over 500 through intensive management. Innovative solutions like providing artificial nest platforms have allowed Osprey populations to rebound dramatically in regions where natural nesting sites had disappeared. These success stories demonstrate that with sufficient resources, scientific understanding, and public support, even the most endangered raptors can recover from the brink of extinction.

Community-Based Conservation Approaches

Engaging local communities has emerged as essential for effective raptor conservation, particularly in regions where human-wildlife conflict drives persecution. The Harpy Eagle Conservation Program in Panama exemplifies this approach, working with indigenous communities to establish economic incentives for forest preservation through ecotourism. In Israel, the nationwide effort to restore Griffon Vulture populations involves Bedouin communities as conservation partners, employing former poachers as wildlife guardians. Educational initiatives that highlight the ecological and cultural value of raptors have successfully reduced persecution in multiple regions, particularly when coupled with compensation schemes for verifiable livestock losses. These community-centered approaches recognize that sustainable conservation must address human needs alongside wildlife protection, creating shared investment in raptor survival.

Future Prospects and Conservation Priorities

The future of the world’s rarest raptors depends on immediate, coordinated conservation action across multiple fronts. Habitat protection remains paramount, with research indicating that protected area expansion must prioritize the specific forest types and structural elements required by specialist raptors rather than simply increasing total coverage. International agreements on pesticide regulation need stronger enforcement mechanisms, particularly in developing nations where hazardous chemicals banned elsewhere remain in widespread use. Climate adaptation strategies for raptors must include preserving migration corridors and maintaining habitat connectivity to allow for range shifts. Perhaps most critically, sustainable funding mechanisms for long-term conservation efforts must be established, as the slow reproductive rates of most threatened raptors necessitate decades of protection before populations can stabilize.

Conclusion

The rapid disappearance of the world’s rarest raptors represents both an ecological tragedy and a conservation challenge of the highest order. These magnificent birds—evolutionary marvels that have perfected the art of aerial predation over millions of years—now depend entirely on human intervention for their survival. Their decline serves as a powerful indicator of environmental degradation extending far beyond individual species. Yet the demonstrated recovery of birds like the Peregrine Falcon and California Condor offers hope that with sufficient commitment, even the most endangered raptors can return from the brink. The fate of these apex predators ultimately rests in our hands, challenging us to create a world where the silent wings of eagles, falcons, and hawks continue to cast their shadows across landscapes worldwide.