In the prehistoric landscapes of Australia, amid dense eucalyptus forests and vast grasslands, a massive avian titan once dominated the ecosystem. Standing taller than the average human and weighing several hundred pounds, the Dromornis stirtoni—commonly known as Stirton’s thunderbird or mihirung—was one of the largest birds to ever walk the Earth. Unlike its modern cousins that grace our skies with elegant flight, this imposing creature was completely flightless, with tiny vestigial wings dwarfed by its enormous body. While extinct for millions of years, the discovery of fossilized remains has allowed scientists to piece together the story of this fascinating creature, offering a glimpse into Australia’s ancient past when megafauna ruled the continent long before human arrival. The tale of this flightless giant provides a captivating window into evolutionary history and the diverse wildlife that once called Australia home.

The Discovery of Australia’s Giant Bird

The first fossils of the Dromornis species were discovered in the 1870s by Australian explorer and naturalist Frederick McCoy, though the most complete specimens of Dromornis stirtoni weren’t unearthed until much later expeditions in the Northern Territory. When paleontologists began piecing together the massive bones, they quickly realized they were dealing with something extraordinary—a bird of truly gigantic proportions. The most significant finds came from the Alcoota fossil beds in the Northern Territory, which have yielded remarkably well-preserved specimens that have been crucial to understanding this prehistoric giant. These discoveries sparked immediate scientific interest, as they revealed an evolutionary branch of birds entirely different from the familiar emus and cassowaries that would later dominate Australia’s flightless bird niche. The name “Dromornis” derives from Greek words meaning “running bird,” an apt description for this massive terrestrial avian.

Physical Characteristics of the Mihirung

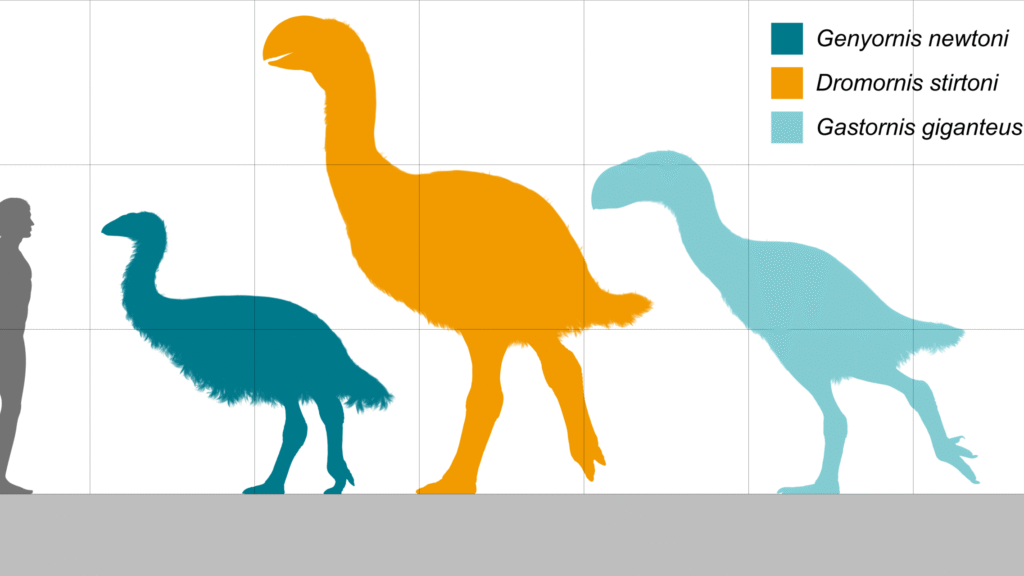

Dromornis stirtoni was a true avian colossus, standing approximately 3 meters (10 feet) tall and weighing an estimated 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds)—roughly the size of a large horse and ten times heavier than today’s largest living bird, the ostrich. Its massive legs were powerfully built to support its enormous weight, with thick bones and heavy musculature that would have made it a formidable presence on the landscape. Unlike modern flightless birds with their downy feathers, paleontologists believe the mihirung may have had sparser feathering, as its massive size would have provided sufficient thermoregulation without dense plumage. The bird’s head was proportionally large with a deep, powerful beak that was likely used for its specialized feeding habits. Perhaps most striking was the contrast between its impressive body and its wings, which had become so reduced through evolution that they were essentially useless appendages, incapable of providing even the slightest lift for this heavyweight champion of birds.

Evolutionary Origins

The evolutionary history of Dromornis stirtoni places it within the family Dromornithidae, an entirely extinct group of large, flightless birds that evolved in isolation on the Australian continent. These birds, collectively known as mihirungs or thunderbirds, were not closely related to modern ratites like emus and ostriches as once thought, but rather represent a remarkable case of convergent evolution. Recent DNA analysis and anatomical studies suggest that dromornithids likely descended from flying ancestors related to modern waterfowl such as ducks and geese—a surprising connection given their enormous size and terrestrial lifestyle. This evolutionary path represents a classic example of island gigantism, where species isolated on islands or island-like continents (as Australia has been for millions of years) tend to evolve larger body sizes due to reduced predation pressure and specialized ecological niches. The dromomithids flourished for over 25 million years, diversifying into several species of varying sizes before ultimately disappearing from the Australian landscape.

Diet and Feeding Habits

Despite its fearsome appearance, paleontological evidence suggests that Dromornis stirtoni was primarily herbivorous, with a specialized diet consisting of tough vegetation that grew in its Late Miocene habitat. Its massive beak was adapted for cropping plants rather than tearing flesh, featuring a strong cutting edge that could efficiently process fibrous plant materials that other animals might find indigestible. Analysis of fossil skulls indicates powerful jaw muscles that would have allowed the bird to crush seeds, nuts, and tough plant matter with ease. Microscopic wear patterns on preserved bill fragments align with those seen in modern plant-eating birds rather than carnivores. The digestive system of these giants likely included a large gizzard with gastroliths—swallowed stones that would have helped grind tough plant material in the absence of teeth, similar to the digestive adaptations seen in modern birds but on a much larger scale to process the substantial quantity of vegetation needed to sustain such a massive body.

Habitat and Range

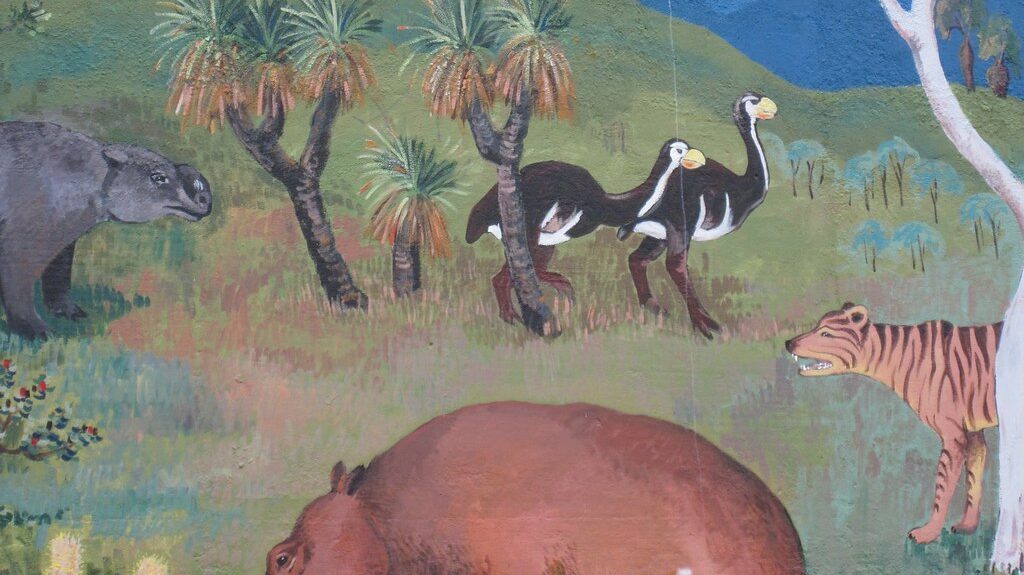

During the Late Miocene to Pliocene periods (approximately 8-5 million years ago), Dromornis stirtoni inhabited regions of what is now Northern Australia, particularly in the Northern Territory where most fossils have been discovered. The environment then was markedly different from the modern Australian outback, consisting of a mosaic of woodlands and grasslands with seasonal watercourses—a substantially more lush landscape than today’s arid interior. Fossil evidence indicates these birds likely preferred semi-open woodland environments where they could browse on a variety of vegetation while maintaining the ability to spot approaching dangers. Their range appears to have been concentrated in central and northern Australia, though related species within the dromornithid family occupied various ecological niches across the continent. Climate records from this period suggest a gradually drying environment, which may have placed increasing pressure on these massive birds that required substantial plant matter to sustain their enormous bodies, potentially contributing to their eventual extinction as their preferred habitat diminished.

Social Behavior and Reproduction

The social structure of Dromornis stirtoni remains somewhat speculative, as behavior doesn’t readily fossilize, but paleontologists have made educated inferences based on modern analogs and fossil evidence. Like many large, flightless birds today, they may have lived in small family groups or loose aggregations rather than large, structured flocks. Their massive size would have demanded substantial individual feeding territories, making dense populations unlikely in all but the most productive environments. Regarding reproduction, fossil nests have not been conclusively identified, but these giants likely produced relatively few, large eggs compared to smaller birds, investing significant parental resources in each offspring. The growth rate analysis of juvenile specimens suggests that young Dromornis may have taken several years to reach adult size—a slow maturation pattern consistent with other mega-avian species and large, long-lived animals. This reproductive strategy, with few offspring and long development periods, would have made their populations particularly vulnerable to environmental changes or new predation pressures.

Adaptations for Flightlessness

The transition from flying ancestors to the flightless giant that was Dromornis stirtoni represents one of the most dramatic examples of evolutionary adaptation in the avian world. As these birds evolved toward their massive size, their flight muscles and keeled sternum (breastbone) progressively reduced, redirecting metabolic resources toward their increasingly powerful legs and digestive system. Their wing bones became dramatically reduced both in size and function, eventually serving no practical purpose beyond possible display behaviors or balance assistance. The bird’s center of gravity shifted lower in its body, providing the stability necessary for a creature of such imposing stature. Additionally, their bone structure evolved away from the hollow, lightweight bones typical of flying birds toward denser, more solid structures capable of supporting their enormous weight—a clear example of how evolution can repurpose anatomical features when selection pressures change. These adaptations allowed Dromornis to exploit terrestrial food sources unavailable to flying birds, ultimately permitting it to reach a size that would have made flight physically impossible regardless of wing morphology.

Predators and Threats

Given its enormous size and power, adult Dromornis stirtoni likely had few natural predators in the Late Miocene ecosystem of Australia. However, the continent was home to several formidable carnivores, including the marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) and large reptilian predators like the enormous Megalania monitor lizard, which may have targeted vulnerable juveniles or even challenged adults under certain circumstances. The most significant threats to these avian giants likely came not from direct predation but from environmental pressures including drought, habitat change, and resource competition. Their massive body size, while providing protection from predators, also required substantial daily food intake to maintain, making them particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations affecting plant productivity. Young Dromornis would have been considerably more vulnerable than adults, potentially facing predation from a wider range of carnivores during their multi-year growth period, placing significant pressure on reproduction rates and population sustainability in changing environmental conditions.

Extinction Theories

The extinction of Dromornis stirtoni and other dromornithids occurred during the Pleistocene period, with the last species disappearing approximately 50,000 years ago—coinciding with both significant climate shifts and human arrival on the Australian continent. This timing has fueled considerable scientific debate about the primary cause of their disappearance. The climate change hypothesis points to Australia’s increasing aridity during this period, which dramatically transformed the landscape from woodland mosaics to more desert-like conditions unsuitable for supporting birds requiring massive plant intake. Alternatively, the human impact hypothesis suggests that early Aboriginal Australians may have hunted these birds or their eggs, or altered the landscape through fire-stick farming practices that changed vegetation patterns. Most contemporary paleontologists favor a combination of these factors—a “perfect storm” where climate-stressed populations with low reproductive rates faced the additional novel pressure of human activity, leading to a decline from which they couldn’t recover. The gradual disappearance of multiple dromornithid species over time suggests a complex extinction process rather than a single catastrophic event.

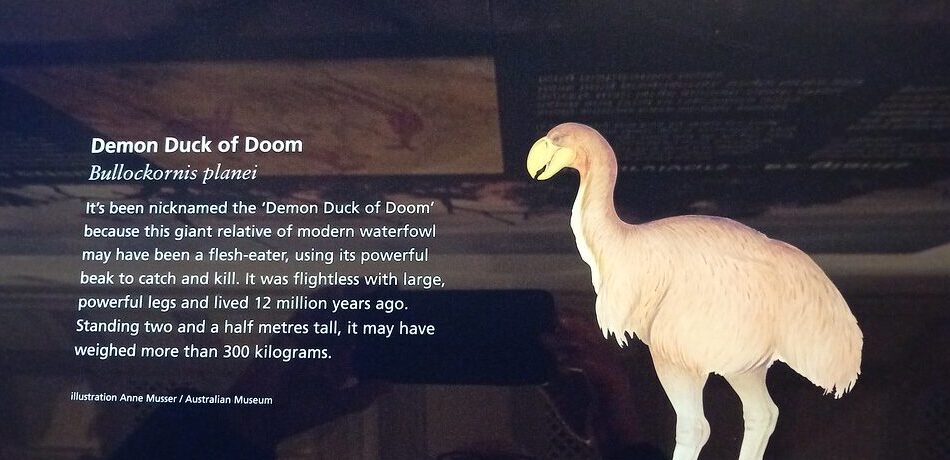

Related Mihirung Species

While Dromornis stirtoni stands as the most imposing member of the dromornithid family, it was just one of several remarkable mihirung species that evolved in Australia over millions of years. The earliest known member, Barawertornis tedfordi, was relatively small by family standards at “only” about 80-100 kg, representing what was likely closer to the ancestral form before extreme gigantism evolved. Another notable relative was Genyornis newtoni, a somewhat smaller but still impressive bird standing about 2 meters tall that survived until much more recently, possibly encountering the first human inhabitants of Australia. The genus Dromornis itself contained multiple species, including the slightly smaller Dromornis australis, first described in the 1870s. Paleontologists have noted interesting evolutionary trends within the family, with some lineages becoming progressively larger over time while others maintained more moderate sizes, suggesting different ecological specializations within the group. This diversity of related species demonstrates how successfully these birds adapted to various Australian environments before their ultimate extinction.

Scientific Research Methods

Unraveling the mysteries of Dromornis stirtoni requires sophisticated scientific approaches that extend far beyond simply excavating fossils. Modern researchers employ advanced imaging techniques such as CT scanning to examine the internal structure of fossilized bones, revealing details about growth patterns, muscle attachments, and even potential brain morphology without damaging precious specimens. Isotopic analysis of fossil material provides insights into diet and environmental conditions by examining the chemical signatures preserved within the ancient remains. Comparative anatomical studies with both modern birds and other extinct species help scientists reconstruct probable movement patterns, feeding mechanics, and sensory capabilities. Additionally, paleontologists use sophisticated dating methods including radiometric dating of volcanic ash layers above and below fossil deposits to establish precise timelines for when these creatures lived. Perhaps most cutting-edge is the extraction and analysis of ancient proteins and DNA fragments that occasionally survive in exceptionally well-preserved specimens, offering molecular evidence of evolutionary relationships that complement anatomical studies.

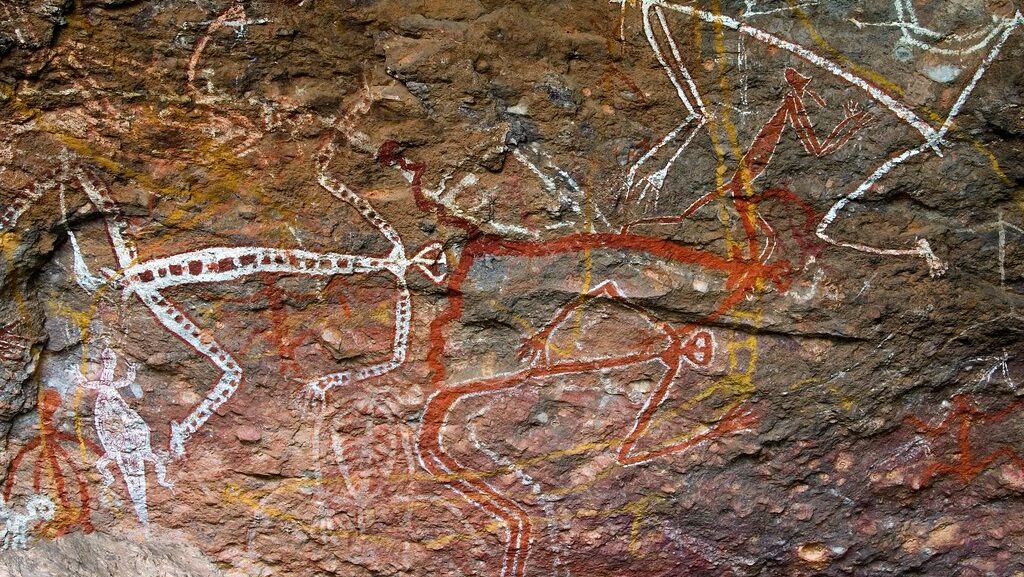

Cultural Significance and Aboriginal Knowledge

The potential overlap between Dromornis stirtoni’s relatives and early human inhabitants of Australia raises intriguing questions about whether these massive birds might be preserved in Aboriginal cultural knowledge. While Dromornis stirtoni itself likely went extinct before human arrival, later dromornithids like Genyornis newtoni almost certainly encountered the first Australians. Some researchers have suggested connections between the dromornithids and certain creatures described in Aboriginal Dreamtime stories, particularly tales of the “mihirung paringmal” (giant emu) from traditions in southeastern Australia. Fascinatingly, rock art in some regions depicts unusually large bird-like creatures that some anthropologists interpret as potential representations of now-extinct mihirungs. Archaeological evidence including eggshell fragments with distinctive burn patterns suggests humans may have collected and cooked eggs from the later dromornithids, establishing a direct interaction between people and these remarkable birds. This intersection of paleontology and cultural knowledge represents an important collaborative research area where Western scientific methods and traditional Aboriginal knowledge can complement each other to build a more complete understanding of Australia’s ancient past.

Museum Exhibits and Public Education

The remarkable story of Dromornis stirtoni has captured public imagination through impressive museum exhibits featuring reconstructed skeletons and scientifically informed life-sized models. The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin houses one of the most significant collections of dromornithid fossils, including spectacular Dromornis specimens from the Alcoota fossil beds. Visitors often express astonishment when confronting the sheer scale of these reconstructions, which provide a visceral understanding of the bird’s imposing presence that mere descriptions cannot convey. Beyond physical exhibits, paleontologists and museum educators have developed interactive digital reconstructions showing how these birds likely moved and behaved, bringing Australia’s ancient past to life for contemporary audiences. These educational efforts extend to school programs, where the story of Dromornis serves as an engaging entry point for discussing evolution, extinction, climate change, and Australia’s unique natural history. The continuing fascination with these avian giants demonstrates how paleontology can connect people with the distant past, inspiring wonder and scientific curiosity about Earth’s remarkable biological heritage.

Conclusion

The story of Dromornis stirtoni offers a fascinating glimpse into Australia’s prehistoric past—a time when giants walked the landscape and evolution shaped extraordinary creatures unlike anything alive today. These flightless titans represent a remarkable evolutionary experiment, transforming from modest flying ancestors into some of the largest birds that ever existed through millions of years of adaptation to Australia’s unique environment. While they ultimately vanished from Earth, their fossilized remains continue to yield scientific insights and inspire wonder. As we piece together their story through ongoing research, these ancient birds remind us of nature’s remarkable capacity for change and the dynamic history of life on our planet. The mihirungs stand as powerful symbols of Australia’s distinctive evolutionary path—a biological heritage as remarkable and unique as the continent itself.