When birds vanish without explanation, they leave behind ecological mysteries that challenge our understanding of migration patterns, environmental changes, and human impact on wildlife. The disappearance of bird species, whether temporary or permanent, often signals deeper environmental issues and raises important questions about our natural world. From centuries-old extinctions shrouded in legend to modern-day population collapses that baffle scientists, these avian vanishing acts represent some of ornithology’s most perplexing cases. This exploration of history’s most mysterious bird disappearances takes us across continents and through time, revealing stories of scientific detective work, ecological warnings, and occasionally, surprising rediscoveries.

The Passenger Pigeon: From Billions to None

Perhaps no bird disappearance is more dramatic or sobering than that of the passenger pigeon, which went from being North America’s most abundant bird to complete extinction in just a few decades. In the early 1800s, these birds darkened skies with flocks so vast they took days to pass overhead, with population estimates reaching into the billions. By 1914, the last passenger pigeon—a captive female named Martha—died at the Cincinnati Zoo, marking the end of a species. What makes this disappearance particularly mysterious isn’t the fact that they were hunted (which they were, mercilessly), but the stunning rapidity of their collapse once their numbers fell below a certain threshold, suggesting unknown ecological mechanisms that prevented recovery even after hunting pressure decreased. Scientists still debate whether their social breeding behaviors made them uniquely vulnerable to population collapse, as they may have required massive colonies to trigger successful reproduction.

The Mysterious Case of the Eskimo Curlew

The Eskimo curlew, once nicknamed the “prairie pigeon” for its abundance, represents one of ornithology’s most puzzling disappearances. These birds made one of the longest migratory journeys of any species, travelling from Arctic breeding grounds to the southern tip of South America. Their decline began in the late 1800s when market hunters targeted them heavily during their migration through the American prairies. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1963 in Texas, though unconfirmed reports have occasionally surfaced since then. What makes their disappearance particularly mysterious is how a bird once so numerous could vanish almost completely without a definitively documented final chapter. Some ornithologists speculate that their specialised feeding habits and the agricultural transformation of their grassland stopover habitats may have delivered the final blow to an already diminished population. Unlike some extinct birds, no museum holds preserved tissue samples that could potentially yield DNA for genetic studies or future de-extinction considerations.

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker: Extinction or Evasion?

The ivory-billed woodpecker represents perhaps the most tantalising and controversial bird disappearance in North American ornithology. This magnificent woodpecker, sometimes called the “Lord God Bird” for the exclamation it inspired when spotted, was declared extinct multiple times throughout the 20th century. However, possible sightings in 2004 in Arkansas sparked worldwide excitement and a massive search effort that continued for years. The mysterious aspect of this disappearance lies in the continuing debate about whether isolated populations might still exist in remote southern swamps. Despite sophisticated search techniques, including automated recording devices, drone surveys, and thousands of hours of field work by experts, no conclusive evidence has been found. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially declared the bird extinct in 2021, but some researchers and birders remain unconvinced, pointing to the vast, inaccessible swamplands where small populations could potentially remain undetected. This case highlights the difficulty of proving absence and the phenomenon known as “extinction of experience,” where each generation accepts a more impoverished natural baseline.

The Bermuda Petrel’s Near-Miss with Oblivion

The Bermuda petrel, or cahow, demonstrates how a bird can disappear from human knowledge yet somehow survive against overwhelming odds. This seabird was thought extinct for over 300 years following European colonisation of Bermuda in the early 1600s. The disappearance seemed logical—introduced predators and intensive hunting had apparently eliminated the entire population. Then, in an ornithological sensation, living cahows were rediscovered in 1951 when researchers found 18 nesting pairs on tiny offshore islets. The mystery in this case isn’t just how the birds survived for centuries without detection, but how such a small population avoided the genetic bottleneck that typically dooms isolated groups. Scientists have since determined that these birds are extremely long-lived (potentially reaching 50+ years) and maintain strict natal philopatry (returning to birth sites to breed), which may have helped their hidden population persist. Today, through intensive conservation efforts, their numbers have grown to over 140 breeding pairs, making this one of the few “Lazarus species” to return from presumed extinction.

The Vanishing Act of the Spix’s Macaw

The haunting disappearance of the Spix’s macaw from Brazil’s caatinga (dry forest) represents one of the most well-documented bird vanishings in history. This striking blue parrot, immortalised in the animated film “Rio,” was driven to extinction in the wild through a perfect storm of habitat destruction and relentless trapping for the pet trade. The last known wild individual, a lone male who had bonded with a female blue-winged macaw, disappeared in 2000, creating one of the most poignant images in conservation, a bird so loyal to its territory that it remained even after all others of its kind were gone. What makes this disappearance particularly mysterious is how such a distinctive, relatively large bird could decline so dramatically without earlier conservation intervention. Genetic analysis of the approximately 160 birds remaining in captivity revealed another puzzle: despite appearing identical, the population showed unexpected genetic diversity, suggesting that birds might have been captured from unknown populations in areas never surveyed by ornithologists. In a hopeful turn, a reintroduction program began in 2022, returning captive-bred Spix’s macaws to specially protected areas of their former range.

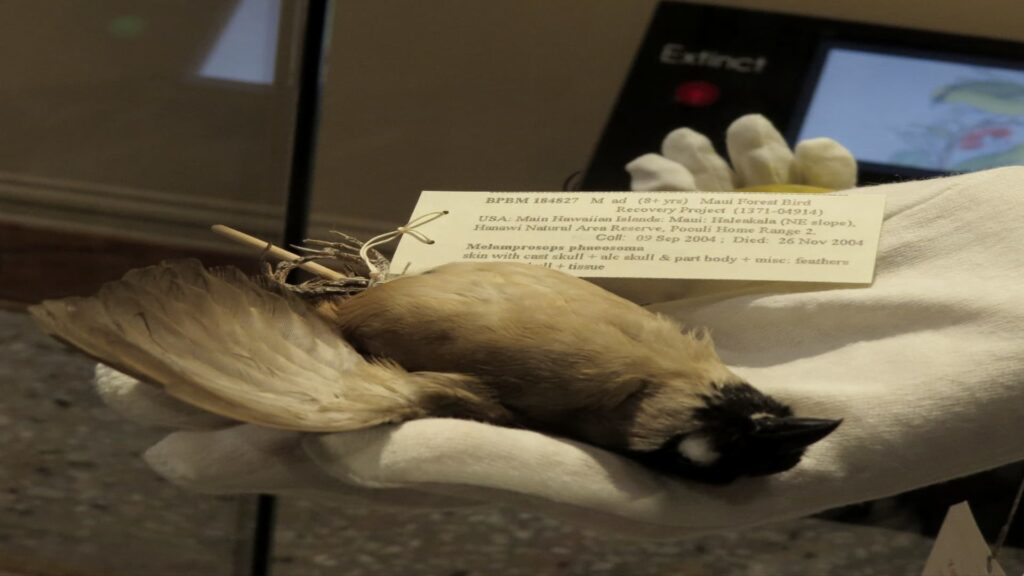

The Po’o-uli: Hawaii’s Vanished Honeycreeper

The disappearance of the po’o-uli (black-faced honeycreeper) represents one of the most rapid and poorly understood bird extinctions in modern times. This distinctive Hawaiian forest bird was only discovered by science in 1973, and by the late 1990s, researchers could find just three individuals remaining in the wild. Despite heroic conservation efforts, including the capture of one bird for potential captive breeding, the species slipped away—the last known individual died in captivity in 2004, and no others have been confirmed since. The mysterious aspect of this disappearance lies in how quickly it happened and how little we understood about the species’ basic biology before it vanished. Scientists were never able to determine exactly what caused the po’o-uli’s precipitous decline, though suspects include avian malaria, habitat degradation, and introduced predators. The bird’s specialised feeding habits—it used its unique bill to extract native tree snails from their shells—may have made it particularly vulnerable to ecological changes. This case represents a sobering reminder of how quickly species can disappear even after their discovery, leaving more questions than answers.

The Slender-Billed Curlew’s Silent Fade

The slender-billed curlew presents one of Eurasia’s most perplexing avian disappearances, having gone from a common migratory species to near-certain extinction with very little scientific documentation of its decline. This elegant wading bird once migrated between breeding grounds in the Siberian wetlands and wintering areas in the Mediterranean basin. Despite being relatively widespread in the 19th century, sightings became increasingly rare throughout the 20th century. The last confirmed breeding record dates back to 1924, and the last universally accepted sighting occurred in Morocco in 1995. What makes this disappearance particularly mysterious is that the bird’s breeding grounds were never definitively identified, despite being a rather large and distinctive species. The leading theory suggests that the drainage of wetlands along its migratory route progressively eliminated critical stopover habitat, but without knowing its exact breeding requirements, scientists cannot fully explain its vanishing. Unlike many extinct birds, there was no concentrated effort to hunt it to extinction, making its disappearance even more puzzling. Today, despite occasional claimed sightings, most ornithologists believe the species is extinct, having slipped away with many fundamental questions about its life history unanswered.

The New Zealand Bush Wren: Extinction by Lighthouse

The story of the New Zealand bush wren (Xenicus longipes) contains one of the strangest and most unexpected mechanisms of bird disappearance ever recorded. This tiny, nearly flightless bird survived millions of years in predator-free New Zealand, only to face rapid extinction following human colonisation and the introduction of mammalian predators. By the 1960s, the last known population survived only on rat-free Kaimohu Island, a small, steep-sided island with a lighthouse. In a tragic twist that highlights the fragility of island ecosystems, this final population was exterminated in 1972 when a lighthouse keeper’s cat systematically hunted every individual. What makes this disappearance particularly mysterious is the bird’s incredible persistence through time; it had survived since the Oligocene period (over 23 million years ago) as a living representative of an ancient lineage of birds that diverged before most modern bird families evolved. Scientists continue to question how such an evolutionary survivor, which had weathered countless climate changes and natural disasters, could so quickly succumb to novel threats, and whether any undiscovered populations might have persisted in remote areas longer than documented.

The Mysterious Cycles of the Bearded Vulture

The bearded vulture (lammergeier) presents a different kind of mysterious disappearance—one characterised by regional extinctions followed by natural recolonisations across its vast Eurasian and African range. These massive birds, known for their unique habit of dropping bones from heights to access marrow, have vanished from numerous mountain ranges only to reappear decades later. In the Alps, they disappeared entirely in the early 20th century due to persecution, only to successfully recolonise following reintroduction efforts beginning in the 1980s. The mystery lies in how certain populations collapse completely while others persist, despite facing similar threats. Recent genetic studies have revealed that bearded vultures maintain gene flow across thousands of kilometres, with individuals occasionally travelling between mountain ranges that were thought to host completely isolated populations. Their disappearances from regions like the Carpathians and parts of Spain followed patterns that defied simple explanations, with some areas experiencing sudden collapses while nearby populations remained stable. Scientists now believe that their complex social structure, extremely delayed sexual maturity (up to 10 years), and specific habitat requirements create boom-and-bust population dynamics that humans have often misinterpreted as permanent local extinctions.

The Carolina Parakeet: America’s Lost Parrot

The disappearance of the Carolina parakeet, North America’s only native parrot species, remains one of ornithology’s most puzzling cases. These colourful, social birds ranged from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Atlantic coast to eastern Colorado until the early 20th century. The last captive individual died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918 (remarkably, in the same cage where the last passenger pigeon had died four years earlier). What makes their disappearance mysterious is the combination of factors involved and the speed of their final decline. While hunting certainly played a role—their feathers were used in ladies’ hats, and farmers shot them as agricultural pests—this doesn’t fully explain their complete extinction. Some scientists have proposed that a poultry disease might have struck the diminished wild populations, while others suggest their social nature proved fatal, as flocks would circle repeatedly over fallen flock-mates, making them easy targets for hunters. Perhaps most intriguing is recent genetic research on museum specimens suggesting that Carolina parakeets maintained healthy genetic diversity until near the very end, indicating their extinction wasn’t due to inbreeding problems that often plague small populations.

The Bachman’s Warbler: A Southern Mystery

The Bachman’s warbler represents one of the most enigmatic disappearances among North American songbirds, having gone from locally common to presumably extinct with remarkably little scientific documentation. This small yellow and black warbler nested in southeastern swamp forests and wintered in Cuba, but was always somewhat mysterious to ornithologists—its nesting habits were poorly documented, and it seemed to undergo population fluctuations even before its serious decline. The last widely accepted sighting occurred in 1988 in Louisiana, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared it extinct in 2021. What makes its disappearance particularly puzzling is that while habitat loss certainly played a role (particularly the clearing of canebrakes it depended on), other warblers facing similar pressures did not vanish completely. Some researchers have suggested that its Cuban wintering grounds may hold the key to understanding its extinction, as deforestation there was extensive during the period of the bird’s decline. Even more mysterious are occasional claimed sightings that continue to this day in remote southern swamps, though none have been confirmed with photographic evidence. Whether this species still exists in some overlooked corner of its range or has truly vanished remains an open question that haunts birders and conservationists.

The Strange Case of the Aldabra Rail

The Aldabra rail provides perhaps the most hopeful and scientifically fascinating case of bird disappearance and reappearance in the ornithological record. This flightless bird, endemic to Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles, completely disappeared around 136,000 years ago when rising sea levels submerged its island habitat. What makes this disappearance and subsequent reappearance unprecedented is that the same species effectively evolved twice. When sea levels later receded, exposing the atoll once again, flying white-throated rails from Madagascar recolonised Aldabra and, remarkably, evolved into flightless birds nearly identical to their extinct predecessors. Scientists confirmed this extraordinary case of iterative evolution by comparing fossils from before the extinction event with modern specimens. The mystery lies in understanding the precise environmental pressures that would drive the same evolutionary pathway twice, creating physically identical birds separated by over 100,000 years. This natural experiment demonstrates how island environments can shape species in predictable ways and suggests that, under certain circumstances, evolution may be more repeatable than previously thought. The Aldabra rail’s story challenges our understanding of extinction as a permanent condition and raises questions about the potential predictability of evolutionary processes.

The Great Auk: First Modern Extinction

The great auk’s disappearance represents the first well-documented modern bird extinction and contains elements of mystery that continue to intrigue scientists. These flightless seabirds, sometimes called the “northern penguin” (though unrelated to true penguins), once ranged across the North Atlantic from Canada to Norway until their final extinction in the mid-19th century. The last confirmed pair was killed on June 3, 1844, on the island of Eldey off Iceland, when collectors strangled the birds and smashed their eggs. What remains mysterious about their disappearance is why a species that had survived intensive hunting by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years suddenly collapsed when European exploitation intensified. Recent archaeological evidence suggests great auks were actually more abundant and widespread than previously believed, making their rapid final decline even more perplexing. Some researchers now believe that climate changes during the Little Ice Age may have concentrated the remaining birds at fewer breeding sites, making them more vulnerable to hunting pressure. Perhaps most troubling is the cultural loss their extinction represents—these birds featured prominently in the mythology and art of northern peoples for millennia, creating a void in cultural heritage that paralleled their ecological absence.

Conclusion

As we reflect on these mysterious bird disappearances, patterns emerge that should give us pause. Many vanished species were once incredibly abundant, challenging the assumption that common species are immune to extinction. Others highlight the complex interplay between direct human exploitation, habitat modification, and introduced species that can push even resilient birds beyond their adaptive capacity. These disappearances remind us that extinction is rarely simple or inevitable—it results from specific pressures that, if understood and addressed in time, might be prevented. Perhaps most importantly, these stories reveal how much remains unknown about even well-studied species, and how quickly birds can vanish before we fully understand their ecological roles or biological requirements. As climate change and habitat loss continue to pressure bird populations worldwide, these historical mysteries serve as both warnings and calls to action to prevent today’s common species from becoming tomorrow’s enigmatic disappearances.