Islands across our planet have long served as evolutionary laboratories, producing some of the most remarkable and specialized birds ever to exist. Protected by geographic isolation, these avian species developed unique adaptations to their specific environments, often losing the ability to fly as they evolved without mammalian predators. When humans arrived on these previously untouched shores, they brought devastation that many island birds could not withstand. This article explores the fascinating and tragic stories of island avian species that vanished following human contact, examining what made them special, how they disappeared, and what their loss teaches us about conservation today.

The Vulnerability of Island Evolution

Islands represent unique evolutionary crucibles where birds often developed in the absence of mammalian predators, leading to dramatic adaptations not seen in continental species. Without the constant pressure to escape ground predators, many island birds evolved reduced or completely lost flight capabilities, channeling their energy instead into different survival strategies. Large body sizes, specialized feeding adaptations, and trusting behaviors became common evolutionary paths. These same adaptations that made island birds perfectly suited to their isolated homes ultimately became fatal vulnerabilities when humans arrived. The geographic isolation that fostered their specialized evolution also meant island birds had nowhere to escape when their habitats were destroyed, making extinction particularly swift and devastating for many unique species.

The Tragic Tale of the Dodo

Perhaps no extinct bird symbolizes human-caused extinction more powerfully than the dodo of Mauritius, which disappeared just 80-100 years after Dutch sailors first encountered it in 1598. This flightless relative of pigeons evolved in isolation for millions of years, developing a large body weighing up to 50 pounds and losing its need for flight in the predator-free environment. The dodo’s fearlessness around humans made it easy prey, while introduced rats, pigs, and monkeys devastated its single-egg nesting strategy by consuming eggs and chicks. Contrary to popular belief, direct hunting was only part of the dodo’s downfall; the cascading ecological impacts of forest destruction and invasive species played equally significant roles. The dodo’s rapid extinction represents one of the first documented cases of human-caused species loss and has transformed the bird into an enduring symbol of extinction itself.

The Diverse Moa of New Zealand

New Zealand once hosted an extraordinary family of flightless birds known as moa, comprising nine species ranging from turkey-sized forest dwellers to the giant Dinornis robustus that stood nearly 12 feet tall. These remarkable birds evolved over millions of years in the absence of mammalian predators, becoming the dominant herbivores in New Zealand’s diverse ecosystems. When Polynesian settlers (Māori) arrived around 1300 CE, they encountered this evolutionary marvel and hunted moa extensively for their meat, bones, and eggs. Archaeological evidence suggests moa populations collapsed with shocking rapidity, with all species extinct within just 100-160 years of human arrival. The disappearance of these gentle giants represents one of history’s most dramatic examples of human-caused extinction, radically transforming New Zealand’s ecological systems and demonstrating how quickly even abundant species can vanish when faced with novel human pressures.

Hawaii’s Spectacular Honeycreepers

The Hawaiian Islands once hosted one of evolution’s most remarkable adaptive radiations: the Hawaiian honeycreepers. From a single finch-like ancestor that arrived millions of years ago evolved over 50 species of birds with an astonishing diversity of bill shapes and feeding strategies. Some developed long, curved bills for extracting nectar from specific flowers, while others evolved thick bills for cracking seeds or straight bills for insect-catching. When Polynesians arrived around 400 CE, followed by Europeans in 1778, this evolutionary treasure trove began to collapse. Habitat destruction, introduced predators like rats and cats, avian diseases carried by introduced mosquitoes, and direct hunting decimated honeycreeper populations. Of the original honeycreeper diversity, more than half of the species are now extinct, with many of the surviving species critically endangered, representing one of the most dramatic losses of evolutionary diversity on Earth.

The Great Auk: The Northern Penguin

The Great Auk was once abundant across the North Atlantic, from Canada to Norway, serving as the northern hemisphere’s equivalent to penguins. Standing about 30 inches tall with a striking black and white coloration, these flightless birds were masterful swimmers that could dive hundreds of feet deep to catch fish. Despite surviving for millennia alongside indigenous human populations who hunted them sustainably, the Great Auk could not withstand commercial exploitation that began in the 16th century. European sailors and settlers harvested them by the thousands for their meat, eggs, and valuable feathers used in pillows and mattresses. The birds’ breeding colonies, confined to just a few remote islands, offered no escape from systematic hunting. The last confirmed pair was killed on June 3, 1844, on Eldey Island off Iceland, when collectors strangled the birds and smashed their egg, marking the final extinction of this magnificent seabird.

Mysterious Extinction of the Elephant Birds

Madagascar once hosted the largest birds that ever lived: the elephant birds, massive flightless creatures standing up to 10 feet tall and weighing over 1,000 pounds. These enormous ratites laid eggs with a capacity of two gallons, the largest single cells ever produced by any vertebrate. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans arrived on Madagascar around 2,000-4,000 years ago, and within a relatively short time, all elephant bird species had vanished. Unlike some other island bird extinctions where hunting evidence is abundant, the exact mechanisms of elephant bird extinction remain somewhat mysterious. A combination of habitat transformation through agricultural practices, hunting of adults, collection of the enormous eggs (which would have fed entire families), and introduced predators likely contributed to their downfall. Their disappearance dramatically altered Madagascar’s ecosystem, as these massive birds had served as important seed dispersers for many of the island’s unique plant species.

The Stephen’s Island Wren: Discovered and Exterminated

Few extinction stories illustrate the vulnerability of island birds more poignantly than that of the Stephen’s Island Wren, a tiny flightless bird from New Zealand. This sparrow-sized bird was officially discovered in 1894 by David Lyall, the lighthouse keeper on Stephen’s Island, who was alerted to its existence when his cat, Tibbles, brought one home as prey. In a tragic turn of events, Lyall’s cat proceeded to hunt the wrens extensively, bringing in several specimens that Lyall preserved and sent to ornithologists. By the time scientists recognized this was a new, flightless species, it was already too late—the cat had essentially hunted the entire population to extinction. While later research has suggested other feral cats were also involved and some wrens may have survived slightly longer, the story remains one of the most rapid documented extinctions following human discovery, demonstrating how quickly introduced predators can eliminate vulnerable island species.

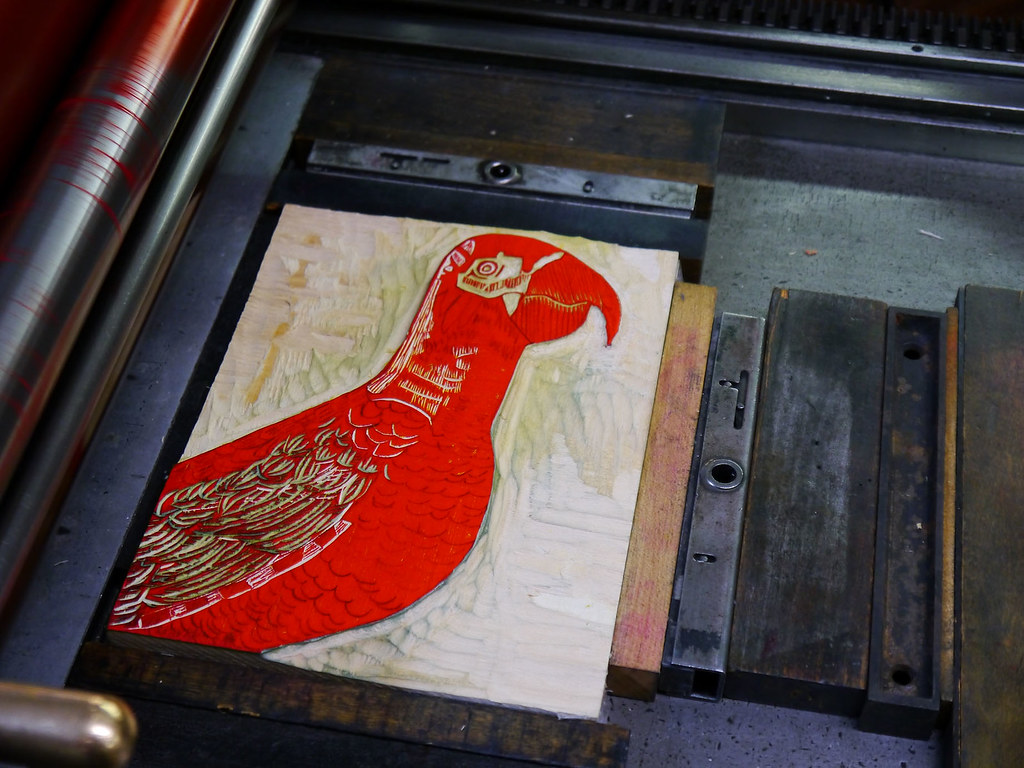

Caribbean’s Lost Macaws

The Caribbean archipelago once hosted at least eight species of magnificent macaws, creating a colorful avian presence across islands like Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, and the Lesser Antilles. Unlike many other extinct island birds, these macaws could fly, but their island homes still made them vulnerable to human pressures. Indigenous peoples hunted Caribbean macaws sustainably for centuries, valuing their feathers for ceremonial purposes, but European colonization brought unprecedented habitat destruction and intensive hunting. The Cuban Macaw, with its striking red, yellow and blue plumage, was the last to disappear, with the final specimen shot in 1864. Archaeological research continues to uncover evidence of previously unknown macaw species, suggesting the pre-Columbian Caribbean was even more biologically diverse than previously thought. The extinction of these birds not only represents a loss of spectacular beauty but also the disappearance of important seed dispersers that helped maintain the Caribbean’s forest ecosystems.

The Huia: Cultural Icon Lost

New Zealand’s huia represents one of the most extraordinary examples of sexual dimorphism among birds, with males possessing short, straight bills while females developed dramatically long, curved bills. This unique adaptation allowed the pair to exploit different food resources while hunting cooperatively—males would chisel away bark while females used their specialized bills to extract wood-boring larvae. The huia held great cultural significance for the Māori people, who treated the bird with respect and used its distinctive black and white tail feathers as high-status decorations. European colonization in the 19th century led to catastrophic decline through habitat destruction, introduced predators, and collecting fervor that intensified as the birds became rarer. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1907, although unconfirmed reports continued until the 1930s. The huia’s extinction represents not just an ecological loss but the disappearance of one of evolution’s most remarkable examples of cooperative feeding adaptations.

The Passenger Pigeon Paradox

While not strictly an island species, the Passenger Pigeon offers a profound lesson about extinction that applies directly to isolated bird populations. Once numbering in the billions across eastern North America, these birds formed flocks so vast they could darken the sky for days. Their social breeding strategy required large colonies to successfully reproduce, creating an unusual vulnerability despite their enormous population. As market hunting intensified in the 19th century, supported by expanding telegraph and railroad networks that allowed hunters to target nesting colonies efficiently, passenger pigeon numbers collapsed with astonishing speed. By the time conservation measures were implemented, the populations had fallen below the critical threshold needed for successful breeding. The last wild passenger pigeon was shot in 1901, and the last captive bird, Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914. This extinction demonstrated that even the most abundant species can disappear rapidly when human pressures exceed their reproductive capacity.

The Carolina Parakeet’s Colorful Demise

North America once hosted its own native parrot species, the Carolina Parakeet, which brought tropical color to eastern forests from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. These social birds traveled in noisy flocks, feeding on seeds, fruits, and remarkably, cockleburs and other toxic plants that they could consume without ill effects. Their vibrant green bodies, yellow heads, and orange faces made them targets for the millinery trade, which used their feathers to decorate fashionable women’s hats in the 19th century. The birds’ social nature contributed to their downfall, as they would circle around fallen flock members instead of fleeing, allowing hunters to shoot entire flocks in succession. Habitat loss through deforestation, persecution by farmers protecting crops, and possibly disease contributed to their decline. The last captive Carolina Parakeet died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918, just four years after the passenger pigeon Martha, in the same cage—a somber coincidence marking the loss of two iconic American birds.

Extinction Cascades: The Broader Ecological Impact

The disappearance of island birds created far-reaching ecological consequences that extended well beyond the loss of the species themselves. Many island plants evolved specifically to be pollinated or have their seeds dispersed by particular bird species, creating tight coevolutionary relationships. When these birds vanished, their partner plants often followed them into extinction or persisted as “ecological ghosts,” species still alive but functionally extinct without their evolutionary partners. On islands like Hawaii and New Zealand, certain plants still produce fruits clearly designed for consumption by birds that no longer exist. The dodo’s extinction, for instance, nearly caused the extinction of the Tambalacoque tree, which apparently depended on the bird to process its seeds; the tree only survived because introduced species like turkeys partially replaced the dodo’s ecological role. These extinction cascades demonstrate how the loss of a single species can trigger a domino effect through ecosystems, causing biodiversity loss far beyond the initial extinction event.

Learning from Past Losses: Conservation Today

The tragic history of island bird extinctions has provided valuable lessons that inform modern conservation efforts. Scientists now understand that island species require specialized protection strategies addressing their unique vulnerabilities to introduced predators, habitat loss, and disease. Success stories like the Chatham Island Black Robin, which was rescued from the brink with just five individuals remaining, demonstrate that dedicated conservation can save even the most endangered island birds. Predator-free sanctuaries, both on offshore islets and within predator-proof fenced areas on larger islands, have become crucial tools for protecting vulnerable species in New Zealand, Hawaii, and elsewhere. Translocation programs moving birds to predator-free islands have created insurance populations for many threatened species. Perhaps most importantly, the documented losses of remarkable island birds have raised public awareness about extinction as a real and permanent consequence of human actions, helping build support for conservation efforts worldwide and creating a more hopeful future for the island birds that remain.

The extinction of island avians following human contact represents one of history’s most profound examples of human-caused biodiversity loss. Each vanished species—from the massive elephant birds to the tiny Stephen’s Island Wren—tells a unique story about evolution’s creative power and human impact’s destructive potential. While we cannot bring back the dodo or the great auk, their stories can inspire stronger protection for vulnerable island species that survive today. By understanding what made these lost birds special and why they disappeared, we gain crucial knowledge for preventing similar tragedies in the future. Their legacy lives on not just in museum specimens and scientific descriptions, but in our growing commitment to ensure that island ecosystems and their remarkable avian inhabitants continue to exist for generations to come.