The animal kingdom has always fascinated us with its extraordinary creatures, some of which possess remarkable adaptations that seem almost mythical. Among these impressive beings stands the terror bird – Phorusrhacidae – a family of prehistoric avian predators whose massive beaks could crush bone with terrifying efficiency. These flightless giants once dominated South American ecosystems as apex predators, using their powerful bills not just for feeding but as lethal weapons. Their existence challenges our perception of birds as gentle creatures and reminds us that nature has experimented with formidable designs throughout evolutionary history. Let’s explore the fascinating world of these remarkable extinct predators that once ruled ancient landscapes with their bone-crushing capabilities.

The Rise of the Terror Birds

Terror birds, or Phorusrhacids, emerged during the Paleocene epoch approximately 62 million years ago, shortly after the extinction of dinosaurs created ecological opportunities for new predators. Their evolution represents a classic example of adaptive radiation, where a group rapidly diversifies to fill vacant ecological niches. The largest and most formidable species of terror birds reached their evolutionary peak during the Pliocene epoch, approximately 5 million years ago. These remarkable creatures continued to thrive across South America until their ultimate extinction around 2.5 million years ago, marking the end of a 60-million-year reign as dominant predators. Their evolutionary success story highlights how birds adapted to ground-dwelling predatory roles when mammals were still in early stages of diversification on the isolated South American continent.

Anatomical Features of the Bone Crushers

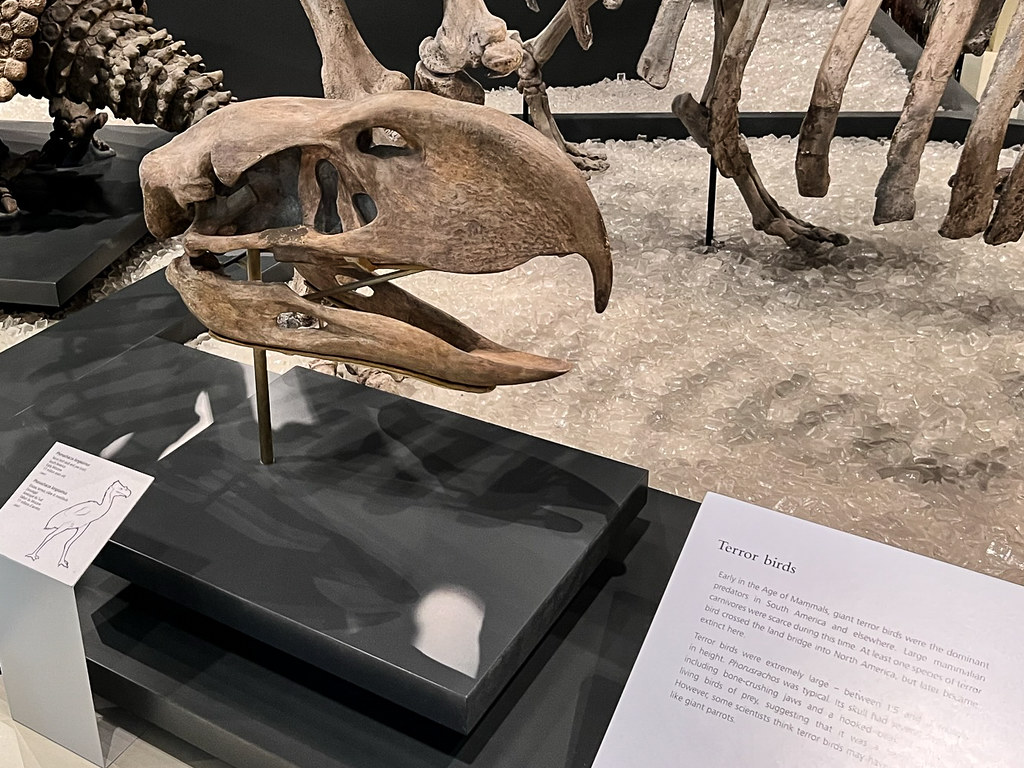

Terror birds possessed an array of specialized anatomical adaptations that made them exceptional predators, but none was more distinctive than their massive heads and powerful beaks. The skull of the largest species, Titanis walleri, could reach over two feet in length, supporting a hooked beak that terminated in a sharp, downturned point perfect for delivering killing blows. Their beaks weren’t just for show—composed of dense keratin reinforced by robust underlying bone structure, these weapons could exert tremendous force, estimated to exceed 750 pounds per square inch in the largest species. Unlike modern birds with lightweight, hollow bones, terror birds evolved reinforced, solid cranial structures that could withstand the extreme forces generated during powerful strikes and bone-crushing activities. Complementing their formidable beaks, they possessed strong neck muscles and specialized vertebrae that allowed them to deliver powerful, axe-like strikes with devastating precision.

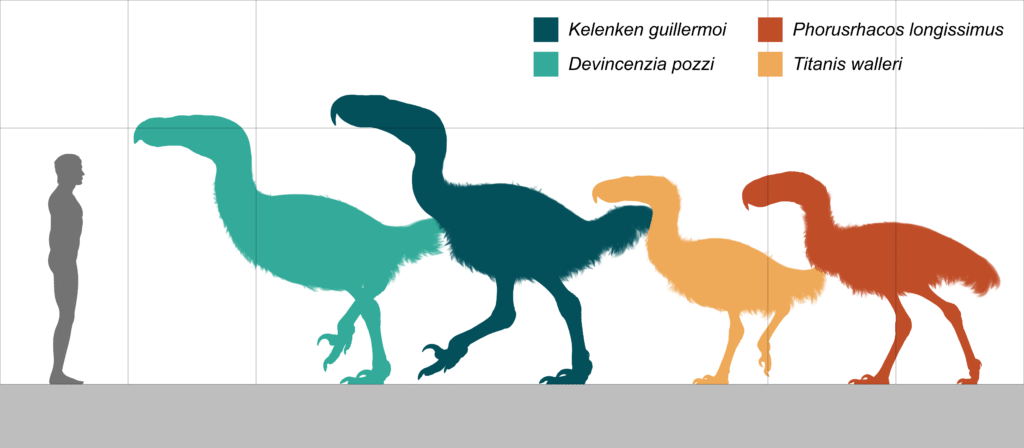

Size and Stature: Giants Among Birds

The most imposing terror bird species, Titanis walleri and Kelenken guillermoi, stood at an astonishing height of up to 10 feet (3 meters), towering over most modern humans. Their massive frames could weigh in excess of 330 pounds (150 kilograms), making them among the heaviest birds to ever walk the Earth. Despite their flightless nature, these birds maintained the lightweight skeletal structure characteristic of avians, though with significant reinforcement in areas critical for predation and bone-crushing activities. Their imposing height gave them a significant advantage in spotting prey across open grasslands, while their robust build enabled them to tackle large mammalian prey that would be inaccessible to smaller predators. Fossil evidence indicates significant sexual dimorphism in some species, with males typically being larger and more robust than females, suggesting complex social structures and possibly territorial or mate-competition behaviors.

The Mechanics of Bone-Crushing Power

The bone-crushing capability of terror birds resulted from a perfect biomechanical storm combining several specialized adaptations. Their beaks functioned like geological pickaxes, concentrating enormous force at the narrow tip while being supported by reinforced skull bones that could withstand the impact stress. Biomechanical studies suggest that rather than using grinding pressure like mammalian bone-crushers such as hyenas, terror birds employed a repeated hacking motion, driving their beaks downward with tremendous force to fracture prey bones. This distinctive feeding approach was supported by specialized neck musculature that could generate explosive downward acceleration, creating forces sufficient to penetrate tough hides and shatter bones. Recent computer modeling studies estimate that the largest terror birds could generate impact forces comparable to the bite force of mid-sized crocodilians, despite using a completely different mechanical approach to bone destruction.

Hunting Strategies of the Terror Birds

Terror birds employed sophisticated hunting strategies that capitalized on their unique physical attributes and the open environments they dominated. Unlike ambush predators, paleontologists believe these birds were active pursuit hunters, using their powerful legs to chase down prey at speeds estimated to reach 30 miles per hour. After running down their quarry, they would employ their massive beaks in devastating downward strikes, targeting vulnerable areas like the spine or skull to quickly incapacitate victims. For larger prey, terror birds likely used repeated powerful strikes to weaken their victims before delivering fatal blows, a strategy evidenced by multiple impact marks found on fossil bones of potential prey animals. Their hunting efficiency was further enhanced by exceptional binocular vision, with eye sockets positioned to provide depth perception crucial for accurately judging striking distance and targeting vital areas of their prey.

Terror Birds’ Ecological Role

As apex predators, terror birds played a crucial regulatory role in South American ecosystems for millions of years, controlling populations of herbivores and smaller predators alike. Their dominance helped shape the evolutionary adaptations of countless prey species, who developed enhanced speed, vigilance, and protective adaptations in response to terror bird predation pressure. Fossil evidence from paleontological sites across South America reveals that these predators occupied diverse habitats ranging from open savannahs to woodland edges, demonstrating their ecological versatility and adaptability. Their position at the top of the food chain meant that adult terror birds had few natural predators themselves, though their eggs and young would have been vulnerable to smaller opportunistic predators and other terror birds engaging in cannibalistic behavior. The ecological void left by their eventual extinction likely triggered significant cascading effects throughout South American ecosystems, allowing mammalian predators to expand into previously dominated niches.

Diversity Within the Terror Bird Family

The Phorusrhacidae family comprised approximately 18 known genera and over 30 species, displaying remarkable diversity in size and specialized adaptations. The smallest terror birds, like members of the genus Psilopterus, stood just two feet tall and likely pursued small prey such as rodents and lizards with greater agility than their larger relatives. Mid-sized species such as Phorusrhacos longissimus represented the ecological equivalent of modern big cats, versatile enough to tackle a wide range of prey sizes with their bone-crushing beaks. The giants of the family, like Kelenken guillermoi with its 18-inch skull, evolved during later periods and represented the peak of terror bird evolution in terms of size and predatory specialization. This diversity allowed terror birds to exploit different ecological niches simultaneously, reducing competition between species and enabling them to dominate the predatory landscape of South America for tens of millions of years.

Scientific Discoveries and Fossil Evidence

The first terror bird fossils were discovered in 1887 by Argentine paleontologist Florentino Ameghino, who named the genus Phorusrhacos, though the significance of these findings wasn’t fully appreciated until decades later. A watershed moment in terror bird research came in 2006 with the discovery of Kelenken guillermoi in Argentina, featuring the largest bird skull ever found and providing unprecedented insights into the maximum size and capabilities of these predators. Advanced technologies like CT scanning and computer modeling have revolutionized our understanding of terror bird biomechanics, allowing scientists to estimate bite forces, striking power, and hunting capabilities with increasing precision. Recent discoveries of terror bird fossils with preserved foot structures have provided vital information about their locomotion, confirming they were cursorial (running) predators rather than the ambush hunters they were once thought to be.

The Great American Interchange and Northern Expansion

For most of their evolutionary history, terror birds were confined to South America, which existed as an island continent following the breakup of Gondwana. Their northern expansion became possible only after the formation of the Panama land bridge approximately 3 million years ago, connecting North and South America in what scientists call the Great American Interchange. Fossil evidence confirms that at least one terror bird species, Titanis walleri, successfully colonized southern North America, with remains discovered in Texas and Florida dating to approximately 2.5 million years ago. This northward expansion brought terror birds into direct competition with established North American predators, including large cats, bears, and other mammalian carnivores that had evolved in isolation from the South American fauna. Ironically, this interchange that offered new territory for terror birds may have contributed to their ultimate extinction, as they faced novel competitors, prey with different defensive adaptations, and changing climatic conditions for which they were ill-prepared.

Extinction of the Bone Crushers

The extinction of terror birds approximately 2.5 million years ago coincided with several major environmental and ecological changes that likely contributed to their downfall. Climate fluctuations during the Pleistocene epoch transformed habitats across the Americas, potentially reducing the open grasslands where these predatory birds excelled at pursuit hunting. The Great American Interchange brought waves of mammalian competitors from North America, including specialized carnivores like cats and dogs that may have outcompeted terror birds for prey resources or even preyed upon their vulnerable eggs and young. Additionally, many of their traditional prey species were replaced by North American mammals with different defensive adaptations, potentially reducing hunting success rates for the specialized terror birds. The combination of these factors—climate change, novel competition, and changing prey bases—created a perfect storm that the highly specialized terror birds could not evolutionarily adapt to quickly enough, leading to their ultimate extinction.

Modern Bird Relatives: Seriemas

The closest living relatives to the mighty terror birds are the modest seriemas, two species of long-legged birds native to the grasslands of central and eastern South America. Standing about 35 inches tall, seriemas (Cariama cristata and Chunga burmeisteri) represent a dramatic downsizing from their formidable ancestors but retain several behavioral and anatomical features that hint at their shared evolutionary history. Like their extinct relatives, seriemas are predominantly terrestrial birds that can run swiftly and possess a hooked beak used for capturing and dismembering prey, though on a much smaller scale limited to insects, reptiles, and small mammals. Perhaps most tellingly, seriemas exhibit a distinctive feeding behavior where they repeatedly slam prey against hard surfaces or strike it with their beaks to kill and dismember it—a possible behavioral remnant of the bone-crushing technique employed by their terror bird ancestors. Genetic and anatomical studies confirm this relationship, making seriemas living windows into the evolutionary legacy of the mighty phorusrhacids.

Terror Birds in Popular Culture

Terror birds have captured the public imagination, appearing in various forms of media from documentaries to science fiction. The BBC documentary series “Walking with Beasts” featured terror birds prominently, introducing millions of viewers to these prehistoric predators through cutting-edge computer animation. In literature, terror birds have appeared in paleontological thrillers and speculative fiction, often portrayed as nightmarish predators pursuing human characters across prehistoric landscapes. Video games featuring prehistoric settings, such as “ARK: Survival Evolved,” include terror bird-inspired creatures as formidable enemies that players must avoid or conquer. Despite occasional scientific inaccuracies in these portrayals, popular culture representations have played a crucial role in raising public awareness about these remarkable extinct predators and generating interest in paleontological discoveries related to terror birds and other prehistoric fauna.

What If Terror Birds Had Survived?

The intriguing question of how our world might differ if terror birds had survived into the present day has fascinated both scientists and speculative biologists. Had they persisted, terror birds might have evolved into diverse lineages filling various predatory niches across the Americas, potentially limiting the evolutionary expansion of mammalian carnivores like wolves and big cats. Human colonization of the Americas would have encountered an additional deadly challenge, possibly altering the pattern and timing of prehistoric human migration through the continents. From an ecological perspective, modern conservation efforts would likely include programs to protect these spectacular birds, much as we now work to preserve large predators like tigers and wolves. The agricultural landscape of the Americas might have developed differently, with specialized defenses against terror bird predation becoming necessary for livestock management in regions where these predators persisted. While purely speculative, such thought experiments highlight the profound impact these bone-crushing predators had on evolutionary history and ecosystem development.

Conclusion

The terror birds stand as remarkable examples of evolutionary specialization, developing bone-crushing capabilities that made them dominant predators for millions of years. Their massive beaks, powerful necks, and imposing stature enabled them to reign as apex predators across South American ecosystems long before mammals evolved comparable predatory adaptations. Though extinction claimed these magnificent creatures approximately 2.5 million years ago, their legacy lives on through scientific research, cultural representations, and their distant relatives, the seriemas. The story of terror birds reminds us that evolution has produced astonishing variations on the predatory theme throughout Earth’s history, with the bone-crushing capability of these flightless giants representing one of nature’s most impressive and fearsome adaptations. As we continue to uncover fossils and develop new technologies to study them, our understanding of these remarkable prehistoric predators continues to evolve, providing fascinating glimpses into Earth’s distant past.