Long before humans dominated Earth, the skies belonged to birds of astonishing proportions. These prehistoric avian giants soared over ancient landscapes, casting shadows that would strike fear into modern observers. While today’s largest birds are impressive, they pale in comparison to these extinct feathered colossi. These ancient birds weren’t just large—they were apex predators, formidable competitors, and ecological forces that shaped their environments. From flightless terrors with bone-crushing beaks to massive flying hunters with wingspans rivaling small aircraft, these prehistoric birds represent nature’s experiments with avian gigantism. Join us as we explore seven of the most terrifying prehistoric birds that would make even the bravest modern human think twice about venturing outdoors in their presence.

Phorusrhacids: The Terror Birds That Ruled South America

Standing up to 10 feet tall with massive hooked beaks designed for ripping flesh, Phorusrhacids—aptly nicknamed “terror birds”—dominated South American ecosystems for over 60 million years following the extinction of dinosaurs. These flightless predators could sprint at speeds approaching 30 mph, making them the apex predators of their environment long before big cats evolved. Their most terrifying feature was undoubtedly their skull, which could measure up to two feet in length and housed a beak capable of delivering crushing blows to prey. Paleontological evidence suggests these birds used a “hack and slash” hunting technique, striking downward with their powerful beaks to inflict devastating wounds on mammals that evolved to fill ecological niches after dinosaurs disappeared.

Argentavis Magnificens: The Largest Flying Bird Ever

Soaring over prehistoric Argentina approximately 6 million years ago, Argentavis magnificens boasted a wingspan of 23 feet—wider than many modern small aircraft. Weighing an estimated 150-170 pounds, this member of the teratorn family would have been a terrifying sight as it cast massive shadows over the Pampas landscape. Scientists believe Argentavis used thermal updrafts to remain airborne, similar to modern condors, but on a much grander scale. Its massive size created evolutionary challenges, likely requiring it to launch from elevated positions and limiting its ability to flap continuously, making it a master of soaring flight that would have appeared like a living aircraft to modern humans.

Gastornis: The European Giant Often Misunderstood

Once portrayed as a ferocious predator similar to terror birds, the 6-foot-tall Gastornis has undergone a scientific reputation rehabilitation in recent years. This massive flightless bird, which lived approximately 56-45 million years ago across Europe and North America, possessed a huge beak initially thought to be designed for tearing flesh. Modern isotope analysis of fossilized bones, however, suggests Gastornis was more likely an herbivore with powerful jaws adapted for crushing tough plant material and nuts. Despite this dietary revision, an encounter with this 400-pound feathered giant would still be terrifying for modern humans, as its massive size and powerful beak could inflict serious damage if the bird felt threatened. The bird’s appearance—combining a massive body with a disproportionately large head—would present an alien and frightening silhouette to contemporary observers.

Dromornis Stirtoni: Australia’s Thunderbird

Australia’s prehistoric ecosystems were home to Dromornis stirtoni, nicknamed the “Thunderbird” or “Demon Duck of Doom,” a flightless bird that towered at 10 feet tall and weighed up to 1,100 pounds. Living approximately 8 million years ago, this massive mihirung (an extinct family of giant Australian birds) possessed a huge beak capable of generating tremendous force. While scientists debate whether it was primarily herbivorous or omnivorous, its sheer size would make it a terrifying sight for any human observer. The bird’s massive legs could deliver powerful kicks capable of disemboweling predators, similar to modern cassowaries but with exponentially more force. Fossil evidence suggests these birds had relatively small brains for their body size, potentially making them unpredictable and dangerous if approached by unfamiliar creatures like humans.

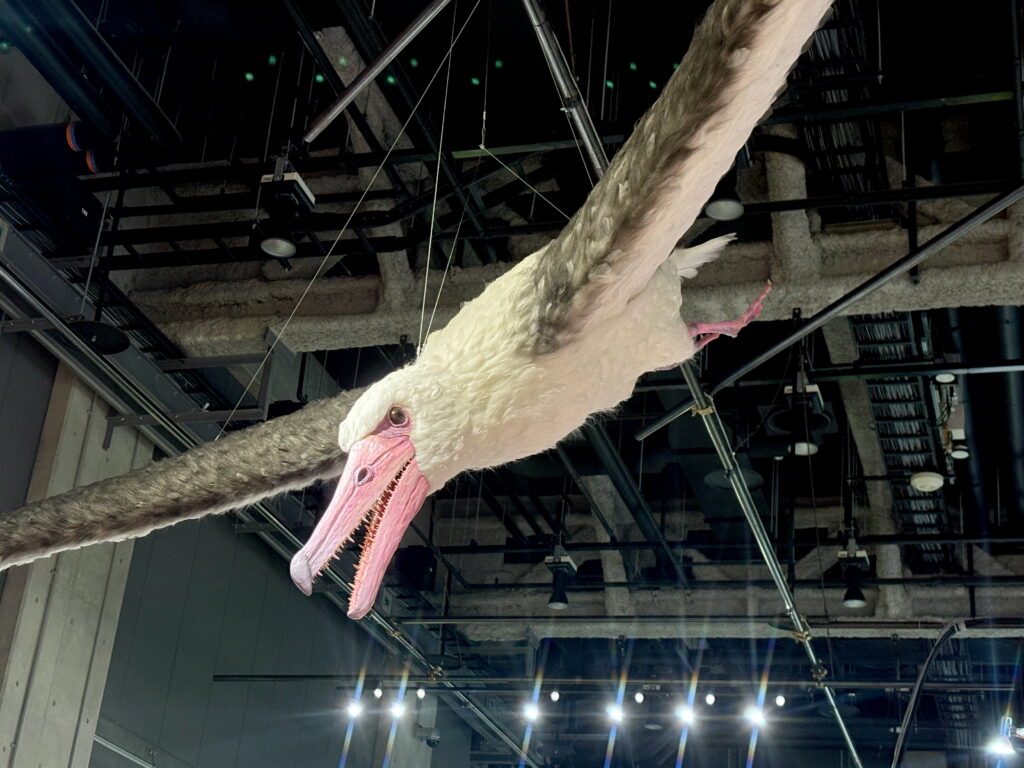

Pelagornis Sandersi: The Bird with the Longest Wingspan

With a wingspan measuring between 20-24 feet, Pelagornis sandersi surpassed even Argentavis as potentially the largest flying bird in Earth’s history when it soared over oceanic environments 25 million years ago. This avian giant belonged to the pseudotooth bird family, characterized by bony tooth-like projections on their beaks used for catching slippery prey from the ocean. Despite its enormous wingspan, Pelagornis had a relatively lightweight body of approximately 50 pounds, an evolutionary adaptation that allowed it to remain airborne despite its massive size. The bird’s most terrifying feature was undoubtedly its serrated beak, lined with bony spikes that would give it a distinctly prehistoric and menacing appearance to modern humans accustomed to the smooth bills of contemporary birds.

Titanis Walleri: North America’s Answer to Terror Birds

When terror birds migrated from South America after the formation of the Panama land bridge, Titanis walleri became North America’s nightmare approximately 5-2 million years ago. Standing 8 feet tall and weighing around 350 pounds, this flightless predator could sprint at tremendous speeds, with some estimates suggesting it could reach 40 mph in short bursts. Unique among terror birds, Titanis possessed a hook on its wing, possibly used as a weapon or for grasping prey while delivering killing blows with its massive beak. This bird was contemporaneous with early humans in North America, making it one of the few giant prehistoric birds that our ancestors might have actually encountered and feared. Its hunting territories stretched across what is now Florida and Texas, where numerous fossils have been recovered.

Dinornis Robustus: The Mighty Moa

New Zealand’s isolated evolution produced the massive moa, with Dinornis robustus (the South Island giant moa) standing as the tallest at nearly 12 feet high when reaching upward. Unlike other prehistoric giant birds, moas evolved without any natural predators until humans arrived, resulting in complete winglessness rather than merely flightlessness. These vegetarian giants could weigh up to 500 pounds and dominated New Zealand’s landscape until approximately 500-600 years ago when Polynesian settlers (Māori) hunted them to extinction. While not predatory, their immense size would make them terrifying to encounter, especially considering their long necks could bring their heads more than 10 feet off the ground. Archaeological evidence shows these birds were contemporary with humans, making them one of the few giant prehistoric birds people actually documented encountering.

Evolutionary Adaptations for Gigantism

The enormous size of prehistoric giant birds represents a fascinating evolutionary phenomenon known as island gigantism in some cases and competitive adaptation in others. In isolated environments like New Zealand (moas) and Madagascar (elephant birds), the absence of mammalian predators allowed birds to grow to enormous sizes and occupy ecological niches typically filled by large mammals elsewhere. For predatory giants like terror birds, their size evolved as an adaptation to fill apex predator roles left vacant after dinosaur extinction. These birds developed specialized skeletal structures to support their massive weight, including reinforced leg bones that were proportionally thicker than those of smaller birds. Their gigantism also frequently corresponded with the loss of flight capabilities, as the metabolic cost of powering flight for such massive bodies became evolutionarily prohibitive.

Hunting Techniques of Prehistoric Giant Birds

The predatory giant birds developed hunting strategies that would terrify modern humans accustomed to contemporary predators. Terror birds like Phorusrhacids and Titanis likely employed ambush tactics, using vegetation as cover before bursting forth at high speeds to run down prey with their powerful legs. Once within striking distance, these birds would use their massive beaks as axe-like weapons, striking downward with tremendous force to deliver killing blows. Fossil evidence suggests some species may have picked up prey in their beaks and slammed them against the ground repeatedly, a behavior observed in some modern birds like herons but scaled to horrifying proportions. For flying giants like Argentavis and Pelagornis, hunting likely involved soaring at high altitudes to spot prey before descending rapidly, using their momentum and specialized beaks to capture prey with surgical precision.

Why These Birds Went Extinct

The extinction of giant prehistoric birds occurred through various mechanisms across different time periods, with climate change and human activity being the two most significant factors. For older species like Gastornis and early terror birds, natural climate shifts and competition with evolving mammals gradually reduced their populations over millions of years. More recent giants like moas and elephant birds survived until approximately 500-1,000 years ago, when human hunters drove them to extinction through direct predation and habitat alteration. Flying giants like Argentavis and Pelagornis faced increasing competition from evolving marine mammals, which may have outcompeted them for food resources. The specialized adaptations that made these birds successful—their gigantic size, specialized beaks, and in many cases flightlessness—ultimately became evolutionary disadvantages when facing rapidly changing environments or new predators like humans.

Modern Birds: The Living Descendants

While the giant prehistoric birds have disappeared, their genetic legacy continues in modern birds that share distant evolutionary relationships. The South American seriema is considered the closest living relative to the terror birds, displaying similar predatory behaviors albeit at a much smaller size of about 3 feet tall. Modern ratites like ostriches, emus, and cassowaries share ancestry with ancient flightless giants and maintain some of their characteristics, including powerful legs, height, and in some cases, aggressive defensive behaviors. The Andean condor, with its impressive 10-foot wingspan, offers a scaled-down glimpse of what massive prehistoric flyers might have looked like, using similar thermal soaring techniques that Argentavis would have employed. These modern descendants, while impressive, represent evolutionary compromises that sacrificed the extreme size of their ancestors for greater sustainability in changing environments.

What If These Birds Existed Today?

If prehistoric giant birds coexisted with modern human civilization, the ecological and cultural implications would be profound. Conservation efforts would be complicated by the territorial requirements of these massive creatures, particularly the predatory species that would require enormous ranges and prey populations to sustain themselves. Human safety concerns would necessitate specialized management protocols similar to those used for dangerous megafauna like tigers and elephants, but potentially more complex given the speed and predatory nature of birds like terror birds. Tourism industries would likely develop around safe viewing opportunities, while scientific research would benefit enormously from studying these evolutionary marvels in their natural habitats. Perhaps most significantly, human development patterns in regions inhabited by these birds would have evolved differently, potentially creating wildlife corridors and protected zones that might have benefited broader conservation efforts.

The prehistoric world was home to avian giants that would seem almost mythological by today’s standards. These seven massive birds—from the axe-beaked terror birds to the enormous flying Pelagornis—represent nature’s experiments with pushing the boundaries of avian evolution. Their disappearance has left our modern world with a tamer avifauna, where the cassowary and ostrich stand as mere shadows of their giant ancestors. Though we can be thankful not to face the prospect of a Titanis hunting party or an Argentavis casting its shadow from above, understanding these prehistoric giants provides valuable insights into evolution, extinction dynamics, and the ever-changing nature of Earth’s ecosystems. These feathered leviathans remind us that birds, the living descendants of dinosaurs, once ruled portions of our planet with the same majesty and terror as their famous reptilian ancestors.