In the aftermath of the dinosaur extinction 66 million years ago, a fascinating ecological reshuffling occurred across Earth’s landscapes. While mammals began their evolutionary journey toward dominance, another group temporarily claimed the mantle of top predator in many ecosystems – birds. Among these avian rulers, none has captured scientific imagination quite like Gastornis (formerly known as Diatryma), a massive flightless bird that once stalked the forests of Europe and North America. Standing nearly 6.6 feet tall with a formidable beak and powerful build, this creature represents a remarkable chapter in evolutionary history when birds, the surviving descendants of dinosaurs, briefly reigned as apex predators. This period challenges our modern perception of birds as primarily small, flying creatures and offers a glimpse into an alternative evolutionary path that might have been.

The Rise of Terror Birds After the Dinosaur Extinction

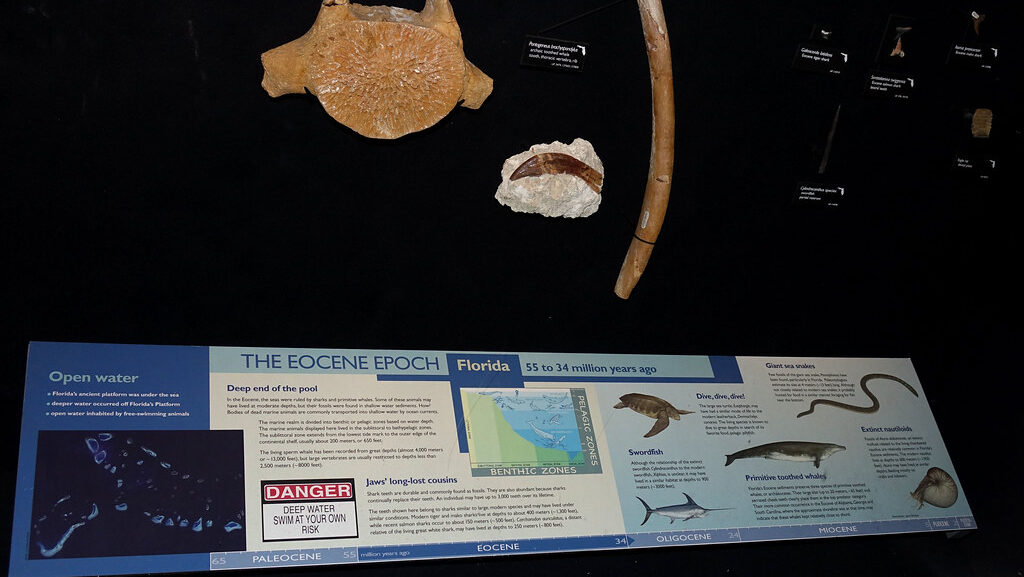

When the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event wiped out non-avian dinosaurs, it created ecological vacancies that survivors quickly evolved to fill. In the early Paleocene and Eocene epochs (roughly 66-33 million years ago), certain bird lineages underwent dramatic adaptations, becoming large, flightless predators. This evolutionary response occurred during a period when mammals were still relatively small, allowing birds to temporarily dominate as large-bodied land predators. Species like Gastornis in the Northern Hemisphere and the phorusrhacids (true “terror birds”) in South America evolved independently to occupy similar ecological niches. These avian giants represent one of evolution’s most fascinating experiments – the transformation of flying dinosaur descendants into ground-dwelling predators that, for a time, sat atop various food chains worldwide.

Gastornis: Anatomy of a Giant

Gastornis was a truly imposing creature, with reconstructions suggesting an average height of about 2 meters (6.6 feet) and estimated weights between 175-200 kilograms (385-440 pounds). Unlike modern flightless birds like ostriches, which have slender builds optimized for running, Gastornis possessed a much more robust frame with thick legs and massive feet that left distinctive three-toed tracks. Its skull measured approximately 45 centimeters (18 inches) in length, featuring a deep, powerful beak with sharp cutting edges but lacking the hooked tip typical of carnivorous birds. The bird’s wings were vestigial, having been reduced to small limbs incapable of flight, while its overall body shape suggested a creature built for strength rather than speed. Skeletal evidence indicates Gastornis had exceptionally strong neck muscles, suggesting it could deliver powerful strikes with its massive beak.

The Controversial Diet of Gastornis

For decades, Gastornis was portrayed as a fearsome carnivore that hunted and devoured early mammals, earning it the nickname “terror bird” in popular culture. However, modern research has significantly challenged this long-held view. Detailed analyses of its beak structure reveal it lacked the sharp, hooked tip typical of predatory birds, instead possessing a more crushing and slicing design. Isotope studies of fossilized bones and eggs suggest a diet surprisingly low in animal protein. Current scientific consensus leans toward Gastornis being primarily herbivorous or omnivorous, potentially specializing in crushing tough plant materials, seeds, nuts, and fruits with its powerful beak, while perhaps opportunistically consuming small animals. This dietary revision doesn’t diminish Gastornis’s ecological significance but rather reframes our understanding of its role in ancient ecosystems.

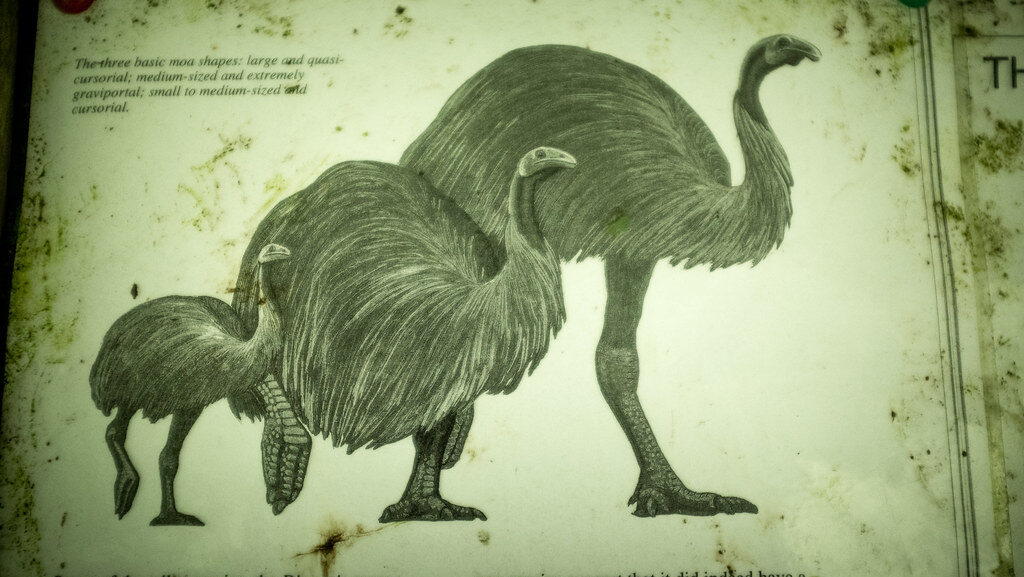

The Evolutionary Origins of Giant Flightless Birds

Gastornis belongs to a fascinating evolutionary phenomenon known as secondary flightlessness – the process whereby flying ancestors gradually lose flight capabilities. This bird descended from flying ancestors in the Galloanserae group, which includes modern chickens, ducks, and geese, though its exact placement remains debated. The evolution toward flightlessness occurred independently multiple times throughout avian history, producing diverse giants like moas, elephant birds, and terror birds (phorusrhacids). These evolutionary pathways typically emerge when birds colonize environments with abundant food resources but few predators, conditions that reduce the survival advantages of flight while favoring larger body sizes. In Gastornis’s case, the post-extinction landscape of the early Paleocene, with its ecological vacancies and small early mammals, provided perfect conditions for the evolution of avian gigantism and ground-dwelling lifestyles.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat Preferences

Gastornis fossils have been discovered across the Northern Hemisphere, with significant finds throughout Europe (particularly France, Belgium, and Germany) and North America (especially Wyoming and New Mexico). This wide distribution indicates these birds were highly successful and adaptable creatures during the Paleocene and early Eocene epochs, roughly 56-45 million years ago. Paleoenvironmental reconstructions suggest Gastornis inhabited densely forested environments, particularly subtropical woodlands that covered much of Europe and North America during this unusually warm period in Earth’s history. These forests would have provided ample plant foods and cover for such large birds, while the humid, tropical conditions supported the lush vegetation needed to sustain creatures of their size. Their presence across continents connected by northern land bridges demonstrates how successful this evolutionary model was in the post-dinosaur world.

Competing with Early Mammals

The relationship between Gastornis and contemporary mammals represents one of the most intriguing ecological dynamics of the early Cenozoic era. During this period, mammals were undergoing their own adaptive radiation, evolving from small, shrew-like creatures into more diverse forms, though most remained relatively small compared to later mammalian megafauna. Gastornis likely competed with early hoofed mammals (condylarths) and primitive carnivores for resources, potentially limiting mammalian evolution in certain niches. Some paleontologists hypothesize that the presence of these giant birds may have influenced the evolution of speed and agility in early ungulates as an anti-predator adaptation, even if Gastornis was not actively hunting adult mammals. This competitive relationship ultimately shifted as mammals diversified and produced their own large predators, eventually contributing to the decline of giant flightless birds in the Northern Hemisphere.

The Phorusrhacids: South America’s True Terror Birds

While Gastornis ruled northern landscapes, a different lineage of giant flightless birds emerged as apex predators in South America – the phorusrhacids, often called “terror birds” due to their undisputed carnivorous nature. Unlike the potentially herbivorous Gastornis, phorusrhacids possessed unmistakably predatory features: sharp, hooked beaks for tearing flesh, proportionally larger skulls, and bodies built for greater speed and agility. The largest species, like Kelenken, stood over 3 meters (10 feet) tall with skulls measuring 71 centimeters (28 inches). These formidable hunters dominated South American ecosystems for over 60 million years while the continent remained isolated, evolving in environments lacking large mammalian competitors. Phorusrhacids’ evolutionary success makes them the longest-reigning avian apex predators in Earth’s history, persisting until approximately 2.5 million years ago – far outlasting their northern counterparts.

Hunting Strategies and Predatory Capabilities

Even if Gastornis wasn’t the dedicated carnivore once imagined, other giant flightless birds of the era employed sophisticated hunting techniques that made them effective predators. Terror birds like the phorusrhacids likely used a combination of ambush tactics and pursuit, relying on powerful legs to deliver devastating kicks and their axe-like beaks to deliver killing blows to prey. Biomechanical studies of terror bird skulls suggest they employed a “hatchet strike” method – using their beaks like pickaxes to repeatedly strike prey with tremendous force. Some species could likely achieve running speeds of 30-40 mph in short bursts, making them formidable pursuit predators. While Gastornis was more robustly built and probably slower, its powerful beak could still generate tremendous crushing force, making it dangerous even if primarily plant-eating. These birds filled predatory niches later occupied by wolves, big cats, and bears, showcasing avian adaptability after the dinosaur extinction.

Scientific Discovery and Changing Perceptions

The scientific understanding of Gastornis has undergone dramatic revisions since its first discovery in the 1850s by French paleontologist Gaston Planté, who found fossil fragments in gypsum quarries near Paris. Initially named Gastornis parisiensis (meaning “Planté’s bird from Paris”), it was later extensively studied and renamed Diatryma, before modern research returned it to its original designation. Early reconstructions portrayed it as a fierce predator similar to the carnivorous phorusrhacids, an image that persisted in scientific literature and popular culture throughout much of the 20th century. The 1970s BBC documentary “Walking with Beasts” famously depicted Gastornis hunting dawn horses, cementing its fearsome reputation in public imagination. However, detailed studies of its beak morphology, biomechanics, and bone chemistry in the early 2000s prompted a major reassessment, with most scientists now favoring a primarily herbivorous lifestyle – demonstrating how paleontological understanding evolves with new evidence and analytical techniques.

The Extinction of Avian Giants

The reign of giant flightless birds as dominant land predators eventually came to an end, though the timing varied significantly by region. Gastornis disappeared from the fossil record approximately 45 million years ago during the middle Eocene epoch, coinciding with significant global cooling and the rise of larger mammalian predators like creodonts and mesonychids. This climatic shift altered forest habitats and likely disrupted the ecological balance that had favored these giant birds. In South America, phorusrhacids persisted much longer due to the continent’s isolation, only facing serious competition when the Panama land bridge formed approximately 3 million years ago, allowing North American predators to migrate southward. The subsequent decline of giant flightless birds represents a fascinating example of how changing climates, continental movements, and interspecies competition shape evolutionary trajectories over millions of years.

Modern Descendants and Evolutionary Legacy

Though Gastornis left no direct descendants, its broader taxonomic group – the Galloanserae – includes some of today’s most familiar birds: chickens, ducks, geese, and their relatives. This evolutionary connection means the humble barnyard chicken shares a distant common ancestor with these imposing giants. The legacy of giant flightless birds continues in modern species like the cassowary, which, though smaller than Gastornis, remains capable of seriously injuring or even killing humans with its powerful kicks and dagger-like claws. The ostrich, Earth’s current largest bird, represents another independent evolution of flightlessness, showcasing how this evolutionary pathway repeatedly emerges under certain conditions. These modern examples help scientists better understand the biomechanics, behavior, and ecological roles of extinct giants like Gastornis, providing living windows into an evolutionary phenomenon that has occurred repeatedly throughout avian history.

Gastornis in Popular Culture

Despite scientific reassessments of its lifestyle, Gastornis continues to capture public imagination as a fierce predator in popular media. The bird featured prominently in BBC’s “Walking with Beasts” documentary series, portrayed hunting prehistoric horses in dramatic sequences that influenced a generation’s perception of these creatures. The History Channel’s “Prehistoric Predators” similarly depicted Gastornis as a carnivorous terror, while various documentaries and books have featured these birds as the “dinosaurs that never went extinct.” Video games like “ARK: Survival Evolved” include Gastornis-inspired creatures as dangerous prehistoric enemies, perpetuating the carnivorous image now questioned by science. This disconnect between current scientific understanding and popular portrayal highlights the challenges in updating public knowledge when new evidence changes long-established views of prehistoric life. Nevertheless, these cultural representations have succeeded in raising awareness of this remarkable chapter in avian evolutionary history.

What Gastornis Teaches Us About Evolution

The story of Gastornis offers profound insights into evolutionary processes and Earth’s dynamic history. It exemplifies convergent evolution – the independent development of similar traits in unrelated lineages – as birds in different regions evolved into comparable ecological roles after the dinosaur extinction. Gastornis demonstrates evolutionary plasticity, showing how quickly species can adapt to fill vacant niches following mass extinctions, transforming from small flying ancestors into imposing flightless giants within relatively brief geological timeframes. The bird’s eventual decline illustrates how evolutionary success is often temporary, dependent on specific environmental conditions and competitive relationships that inevitably change over time. Perhaps most significantly, Gastornis challenges our anthropocentric view of evolutionary “progress,” reminding us that mammals’ eventual dominance wasn’t inevitable – for millions of years, an alternative evolutionary path placed birds at the top of terrestrial food chains, hinting at alternate histories that might have been had circumstances differed slightly.

Conclusion

The remarkable story of Gastornis and its contemporaries reveals a fascinating chapter in Earth’s history when birds briefly claimed dominance as large-bodied land animals. Although scientific understanding has shifted from viewing these creatures as pure predators to recognizing their likely omnivorous or herbivorous diets, their evolutionary significance remains undiminished. These giants emerged from the ashes of the dinosaur extinction to pioneer new ecological roles, demonstrating nature’s remarkable adaptability in the face of catastrophe. Though mammals eventually outcompeted these avian giants across most of the planet, the legacy of this brief “Age of Terror Birds” continues to reshape our understanding of evolutionary processes and possibilities. It serves as a powerful reminder that evolution follows no predetermined path, and that Earth’s history contains numerous alternative ecological arrangements far different from the familiar world we inhabit today.