High above our heads, in the vast expanses of blue sky, exists a remarkable creature that defies our earthbound perspective on life. The common swift (Apus apus) represents one of nature’s most extraordinary evolutionary achievements—a bird that spends almost its entire life in flight, rarely touching land. These aerial virtuosos eat, drink, mate, and even sleep while airborne, coming to land only briefly during breeding season. Their remarkable adaptation to life on the wing showcases nature’s incredible diversity and specialization. As we explore this fascinating bird’s lifestyle, we’ll discover how this master of the skies has pushed the boundaries of what seemed biologically possible, creating a life almost completely detached from the ground below.

The Extraordinary Common Swift: An Introduction

The common swift belongs to the family Apodidae, which derives from the Greek word “apous,” meaning “without feet.” This name reflects how these birds’ feet have evolved primarily for clinging to vertical surfaces rather than perching or walking. With their slender, crescent-shaped wings spanning approximately 40-44 cm (16-17 inches) and their streamlined bodies weighing just 35-56 grams (1.2-2 ounces), common swifts are perfectly designed for their aerial lifestyle. Their distinctive silhouette—often described as resembling a bow and arrow or a boomerang—makes them recognizable even at great heights. Native to Europe, Asia, and Africa, these birds epitomize aerodynamic efficiency, with every aspect of their anatomy fine-tuned for continuous flight.

The Record-Breaking Flight Pattern

In 2016, researchers from Lund University in Sweden made a groundbreaking discovery that forever changed our understanding of the common swift’s lifestyle. By attaching miniature data loggers to several birds, they documented individuals that remained continuously airborne for an astonishing 10 months without landing once. This unprecedented finding confirmed what scientists had long suspected—these birds can indeed spend the vast majority of their lives without touching down. During their annual migration from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa and back, swifts fly approximately 14,000 kilometers (8,700 miles) each way, maintaining nearly constant flight. This remarkable endurance shatters previously held records for continuous flight among birds, cementing the common swift’s reputation as nature’s ultimate aviator.

Aerial Feeding: Dining on the Wing

The common swift has perfected the art of aerial feeding, consuming its entire diet without ever needing to land. These birds are insectivorous, capturing flying insects and airborne spiders exclusively while in flight. With their wide gape and specialized bills, they function essentially as flying nets, scooping up hundreds or thousands of tiny insects daily. A single swift can consume up to 20,000 insects in a single day, making them valuable for natural insect control. They collect food in a special pouch in their throat called a bolus, which can hold up to 1,000 small insects at once before they’re swallowed or brought back to feed nestlings. This feeding strategy allows swifts to remain perpetually airborne while still obtaining all the nutrition they require.

Sleeping While Flying: The Ultimate Multitaskers

Perhaps most remarkably, common swifts have solved the seemingly impossible challenge of sleeping while flying. Research suggests they employ a technique called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep, in which one half of the brain remains active while the other half rests. This allows them to maintain enough awareness to continue flying while still getting necessary sleep. During twilight hours, swifts have been observed ascending to heights of 1,000-3,000 meters (3,300-9,800 feet), where they can glide more efficiently in thinner air while sleeping. Their bodies essentially operate on autopilot, with wing muscles functioning semi-autonomously during these aerial slumbers. This extraordinary adaptation allows them to remain continuously airborne for months without sacrificing the cognitive rejuvenation that sleep provides.

Breeding Season: The Only Time They Land

The only significant interruption to the swift’s aerial lifestyle occurs during breeding season, typically from May to August in the Northern Hemisphere. During this period, swifts will finally touch down to build nests, lay eggs, and raise their young. They typically select high locations like building eaves, church towers, or cliff crevices that allow them to launch directly into flight. Nesting is a relatively brief affair in the context of their lifespan, with adults spending only about two to three months per year engaged in nesting activities. Even during this period, the adults spend most of their time flying, returning to the nest primarily to feed their growing chicks. This limited terrestrial phase highlights just how extraordinarily adapted these birds are to life in the air.

Anatomical Adaptations for Perpetual Flight

The common swift’s body represents an evolutionary masterpiece of adaptations for sustained flight. Their wings are unusually long and narrow, providing excellent gliding efficiency while requiring minimal energy expenditure. Their breast muscles, which power wing movements, are proportionally enormous compared to their body size, comprising up to 25% of their total body weight. Unlike most birds, their legs and feet are small and weak, useful mainly for clinging to vertical surfaces rather than walking or perching. Their metabolic rates can be adjusted with remarkable precision, slowing during passive gliding and accelerating during active hunting. Every aspect of their anatomy, from their lightweight hollow bones to their streamlined feather structure, represents an evolutionary refinement for life spent almost exclusively on the wing.

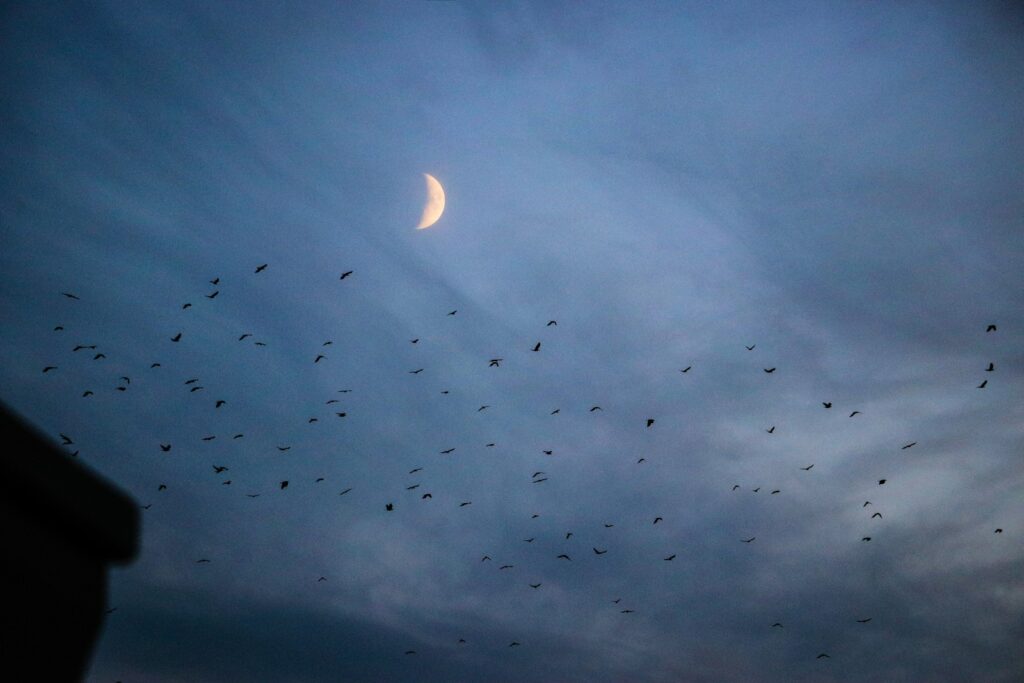

Social Behaviors at High Altitude

Despite their solitary-seeming existence, common swifts maintain complex social structures high above the ground. During summer evenings in Europe, they often form “screaming parties,” where groups of swifts engage in high-speed aerial chases while vocalizing loudly. These gatherings serve multiple purposes, including social bonding, territorial displays, and possibly mate selection. Researchers have noted that non-breeding “helper” swifts sometimes assist breeding pairs, suggesting sophisticated social organizations that extend beyond simple pair bonds. During migration, swifts often travel in loose flocks, although they don’t maintain the tight formations characteristic of many other migratory birds. These social behaviors challenge our perception of swifts as solitary wanderers and reveal the complex community life that unfolds in the aerial realm they inhabit.

Weather Navigation and Flight Adaptability

Common swifts display remarkable abilities to navigate changing weather conditions, often using storms to their advantage. They can detect approaching weather fronts and changes in barometric pressure from great distances, allowing them to adjust their flight paths accordingly. When encountering storms, swifts frequently fly around or above them, sometimes reaching altitudes of 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) to avoid turbulence. More fascinating still, they sometimes deliberately fly to the edges of storm systems to feed on insects that accumulate there, carried by the same air currents. During cold snaps when insects are scarce, swifts can enter a state of torpor to conserve energy, slowing their metabolism while continuing to fly on autopilot. This weather adaptability allows them to maintain their aerial lifestyle through challenging conditions that would ground many other bird species.

Migration Patterns and Global Range

The common swift undertakes one of the most impressive migrations in the bird world, traveling between European breeding grounds and African wintering areas without ever touching down. After hatching and fledging in Europe, young swifts begin an epic journey south to central and southern Africa, where they will remain in continuous flight for up to three years until they reach breeding age. Adult swifts follow similar routes each year, with birds banded in Sweden being spotted as far south as Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Interestingly, different swift populations take slightly different migration routes, with western European birds generally following a more westerly African path than eastern European populations. This enormous migration range means individual swifts may fly more than 2 million kilometers (1.24 million miles) over their lifetime—equivalent to flying to the moon and halfway back.

Conservation Challenges in a Changing World

Despite their aerial prowess, common swifts face numerous conservation challenges in today’s rapidly changing world. Population surveys indicate troubling declines across much of Europe, with the UK reporting a 57% reduction since 1995. One primary threat comes from the renovation and modernization of buildings, which eliminates traditional nesting crevices these birds depend on during breeding season. Climate change also poses risks by altering insect availability and creating more frequent extreme weather events that can disrupt feeding patterns. Light pollution interferes with their navigation during nocturnal migration, while pesticide use reduces their insect food sources. Conservation efforts now include installing specialized swift nest boxes on buildings and protecting traditional nesting sites, but these aerial masters remain vulnerable despite spending so little time in contact with the human world below.

Myths and Cultural Significance

The common swift’s extraordinary lifestyle has inspired human mythology and cultural significance for centuries. In ancient Greek tradition, swifts were associated with the souls of the dead, perhaps due to their seemingly supernatural ability to remain aloft indefinitely. Many European folklore traditions considered harming a swift’s nest to bring bad luck, with some believing it could cause storms or other calamities. In Chinese culture, swifts have been revered for their saliva, which is used to create the prized delicacy bird’s nest soup (though true swift nests are increasingly protected and regulated). Shakespeare referenced swifts in “Measure for Measure,” calling them “temple-haunting martlets” and noting how they choose their nesting sites carefully. Even today, these birds capture human imagination as symbols of freedom and transcendence, representing a life almost completely liberated from terrestrial constraints.

Scientific Research and Recent Discoveries

Recent scientific breakthroughs have dramatically expanded our understanding of the common swift’s extraordinary lifestyle. The development of ultra-lightweight tracking devices weighing less than 1 gram has allowed researchers to follow individual birds throughout their entire annual cycle for the first time. These studies have revealed previously unknown details about their flight patterns, including the discovery that they ascend to different altitudes depending on the time of day. DNA analysis has shed light on their evolutionary history, suggesting their aerial lifestyle evolved gradually over millions of years from ancestors that spent more time perched. Specialized wind tunnel experiments have quantified the remarkable efficiency of swift flight, showing they consume approximately 30% less energy than would be predicted for a bird of their size. As research technology continues to advance, scientists anticipate even more revelations about these aerial masters in coming years.

Related Species: The Swift Family Around the World

While the common swift holds the record for continuous flight, it belongs to a larger family of aerial specialists with remarkable adaptations. The alpine swift (Tachymarptis melba), slightly larger than its common cousin, has been documented flying continuously for up to six months. The white-throated needletail, native to Asia, is considered the fastest-flying bird in powered (non-diving) flight, reaching speeds of 170 km/h (105 mph). The American chimney swift underwent a fascinating habitat adaptation when European settlement reduced hollow tree availability, switching to nesting almost exclusively in chimneys and other human structures. The tiny Vaux’s swift of western North America performs spectacular synchronized roosting displays, with thousands of birds spiraling into hollow trees or chimneys at dusk. Together, these related species demonstrate how the swift family has evolved specialized aerial lifestyles across different environments worldwide, though none quite matches the common swift’s remarkable achievement of near-perpetual flight.

The common swift stands as a testament to the extraordinary possibilities of evolutionary adaptation. As these birds soar above us, rarely touching the ground we’re bound to, they represent a fundamentally different way of existing in our shared world. Their life on the wing challenges our understanding of what’s physically possible and reminds us that nature’s innovations often exceed human imagination. In a world increasingly dominated by human activity, the swift’s aerial lifestyle offers both inspiration and a reminder of how much remains to be discovered about the remarkable adaptations that allow creatures to thrive in seemingly impossible circumstances. Perhaps in understanding these masters of the sky, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a renewed appreciation for the boundless creativity of evolutionary processes that shape our living world.