When we think of prehistoric creatures, dinosaurs often steal the spotlight with their massive size and fearsome appearance. However, the avian world has produced some truly bizarre specimens throughout evolutionary history that rival even the strangest dinosaurs in their peculiarity. These extinct birds, many of which evolved after the dinosaur era, developed extraordinary adaptations that seem almost unbelievable by modern standards. From flightless giants to birds with teeth, the evolutionary experiments of avian history showcase nature’s incredible diversity and adaptability. Let’s explore ten of the most unusual extinct birds that once roamed our planet – creatures so strange they might make even a Tyrannosaurus rex seem conventional by comparison.

The Elephant Bird: Madagascar’s Feathered Giant

The Elephant Bird (Aepyornis maximus) of Madagascar holds the title of the heaviest bird to ever exist, weighing up to 1,600 pounds and standing nearly 10 feet tall. Unlike most large flightless birds with reduced wings, the elephant bird’s wings were practically non-existent, having been evolutionarily eliminated almost entirely. These avian giants laid eggs larger than those of any dinosaur, with volumes of up to 2 gallons – roughly 160 times larger than a chicken egg. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans encountered these birds before their extinction around 1000-1200 CE, with egg fragments often repurposed as containers by early Malagasy inhabitants. Their disappearance likely resulted from a combination of human hunting, habitat destruction, and the collection of their enormous eggs.

Pelagornis: The Largest Flying Bird with Pseudo-Teeth

Pelagornis sandersi, which lived approximately 25 million years ago, had the largest wingspan of any known bird, stretching 20-24 feet across – twice that of the largest living flying bird, the wandering albatross. What made this giant truly bizarre were the bony projections extending from its beak that resembled teeth, though they weren’t true teeth at all. These “pseudo-teeth” were actually specialized serrated bony protrusions that helped Pelagornis grasp slippery prey like squid and fish from the ocean surface. Despite its enormous size, paleontologists believe Pelagornis was an efficient glider that took advantage of thermal currents, much like modern albatrosses, allowing it to stay aloft for days or even weeks with minimal energy expenditure. Its unusual combination of features – massive wingspan, lightweight hollow bones, and toothed beak – made it one of history’s most successful aerial predators.

Hesperornis: The Diving Bird with Real Teeth

Unlike Pelagornis with its bony projections, Hesperornis possessed genuine teeth in its beak – a trait inherited from its dinosaur ancestors that most modern birds have lost. This Late Cretaceous bird, living alongside the dinosaurs around 78 million years ago, was a specialized aquatic predator reaching lengths of up to 6 feet. Hesperornis completely lost the ability to fly, instead evolving powerful hind legs with lobed feet that made it an exceptional diver, similar to modern loons or grebes. What makes Hesperornis particularly strange is the placement of its legs – they jutted sideways from its body, making it awkward and possibly incapable of standing upright on land, suggesting it spent nearly its entire life in water. The combination of reptilian teeth in a specialized diving bird body plan represents one of evolution’s most unusual experiments.

Gastornis: The Terror Bird That Wasn’t

For decades, Gastornis (formerly known as Diatryma) was portrayed as a ferocious predator standing 6 feet tall with a massive head and powerful beak that could tear apart prey in the forests of early Eocene Europe and North America about 55 million years ago. However, recent evidence has dramatically changed our understanding of this bird, revealing one of paleontology’s most significant reinterpretations. Chemical analysis of its fossilized bones shows carbon isotope patterns consistent with a plant-based diet, not meat consumption. Additionally, its beak structure more closely resembles that of seed-crushing birds rather than predatory species. This giant flightless bird, once depicted as a “terror bird” chasing primitive horses, was more likely a gentle herbivore using its powerful beak to crack nuts and crush tough plant material. Gastornis represents how even scientific understanding of extinct species continues to evolve with new evidence.

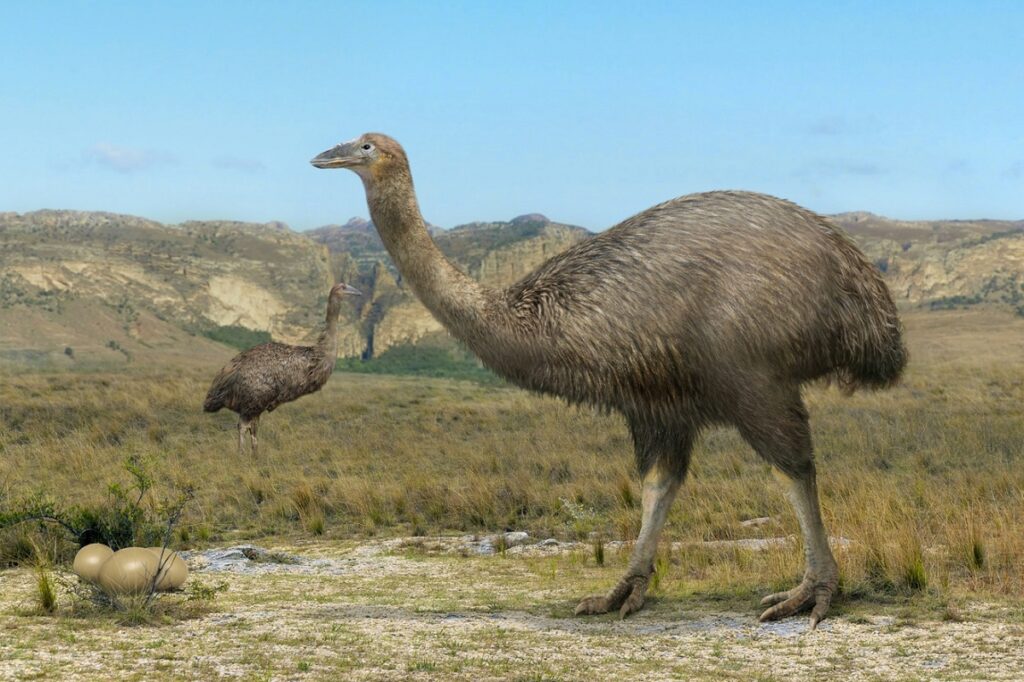

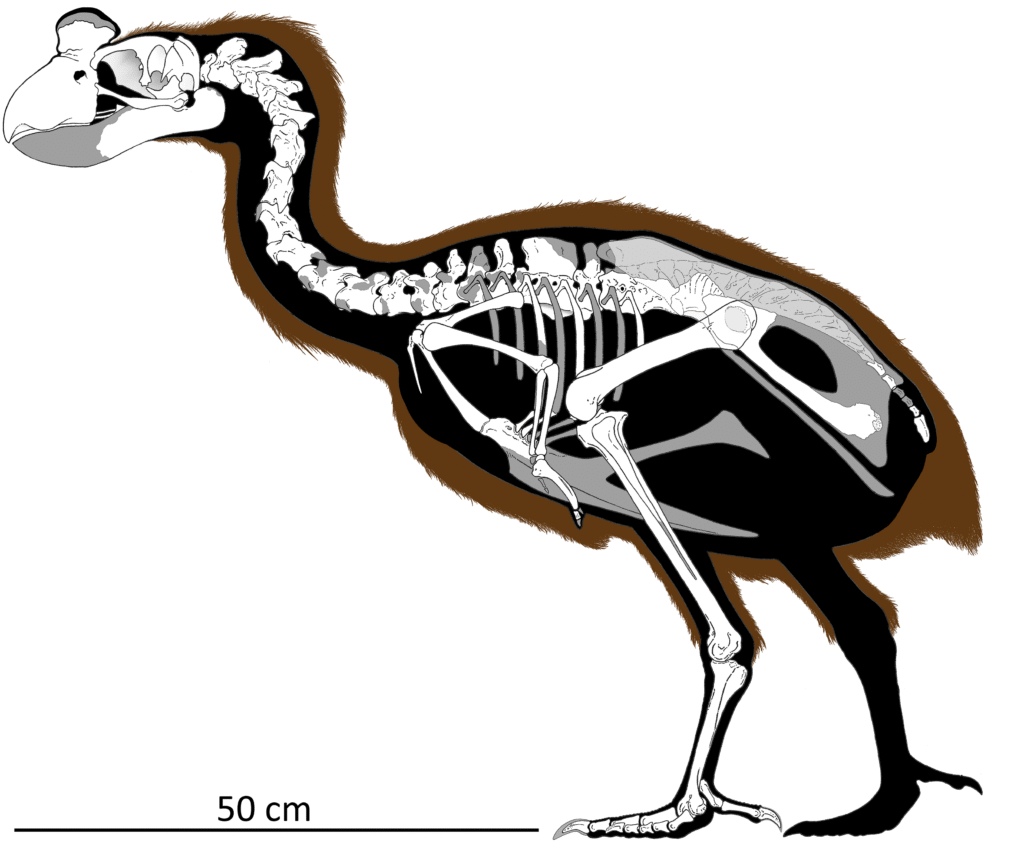

Moa: The Headless Giants of New Zealand

The moa of New Zealand represent one of evolution’s most extreme experiments in bird design, developing into giants that stood up to 12 feet tall with some species weighing over 500 pounds. Unlike other large flightless birds such as ostriches and emus, moa evolved something truly bizarre – a complete absence of even vestigial wings, with no wing bones whatsoever. Perhaps most striking was their unusual body structure that lacked a distinct head – their small skull attached directly to their neck, giving them an oddly headless appearance compared to other birds. The nine species of moa thrived in isolation until the arrival of Polynesian settlers (Māori) around 1300 CE, after which they were hunted to extinction within approximately 100 years. DNA recovered from their well-preserved remains has revealed fascinating details about their ecology and has even raised controversial discussions about potential de-extinction efforts.

Titanis: North America’s Nightmare Bird

Titanis walleri represents the last and largest of the infamous “terror birds” (Phorusrhacidae), standing nearly 8 feet tall and weighing approximately 330 pounds when it roamed Florida and Texas until just 2 million years ago – making it a contemporary of early humans. Unlike other birds that use their beaks for precision, Titanis evolved a hooked beak designed to deliver crushing, hammer-like blows to its prey, functioning more like a weapon than a typical bird bill. What made Titanis particularly unusual was its forelimbs, which had evolved from wings into claw-bearing appendages that could potentially grab and manipulate prey – a feature unknown in modern birds. Paleontological evidence suggests Titanis was an apex predator capable of taking down prey larger than itself, using its speed (estimated at up to 35 mph) and powerful legs to chase down prehistoric horses and other mammals across the North American plains.

Sylviornis: The Chicken That Outgrew a Horse

Sylviornis neocaledoniae from New Caledonia in the Pacific represents one of the most dramatic size increases in avian evolution, essentially a chicken relative that grew to the size of a horse, weighing an estimated 66 pounds. This flightless bird had a bizarrely enlarged head with a bony casque (helmet-like structure) and a uniquely reinforced skull unlike any living bird. What truly sets Sylviornis apart was its reproductive behavior – it constructed massive mound nests up to 13 feet across and 3 feet high, essentially creating artificial incubators for its eggs using rotting vegetation. Archaeological evidence indicates these birds survived until approximately 1,700 years ago when Lapita people settled New Caledonia, suggesting human hunting and habitat alteration led to their extinction. Sylviornis demonstrates how island environments can drive evolution in unexpected directions, transforming a chicken relative into a massive, flightless mound-builder.

Dromornis: The Demon Duck of Doom

Dromornis stirtoni, colorfully nicknamed the “Demon Duck of Doom” by Australian paleontologists, was one of the largest birds to ever exist, standing 10 feet tall and weighing up to 1,100 pounds when it inhabited Australia approximately 8 million years ago. Despite its fearsome modern nickname, this massive flightless bird was likely herbivorous, using its enormous beak to process tough plant materials in Australia’s interior. What makes Dromornis particularly strange is its evolutionary relationship – despite its ostrich-like appearance, genetic and anatomical evidence reveals it was most closely related to modern waterfowl like ducks and geese, making it essentially a duck that evolved to gigantic proportions. Dromornis had an unusually small brain for its massive body size, with a brain-to-body ratio among the smallest of any bird, suggesting limited behavioral complexity despite its imposing physical presence. This bizarre evolutionary experiment in avian gigantism disappeared when Australia’s climate became increasingly arid, eliminating the lush vegetation these enormous birds depended upon.

Bullockornis: The Real “Thunder Thighs”

Bullockornis planei, another member of Australia’s ancient “thunder birds” (Dromornithidae), stood approximately 8 feet tall and weighed around 550 pounds when it lived 15 million years ago in Australia’s Northern Territory. Nicknamed the “Demon Duck of Doom” before the larger Dromornis claimed that title, Bullockornis possessed one of the largest bird skulls ever discovered, with a massive beak that could generate tremendous force. What made this bird particularly unusual was its leg structure – it had enormously thick, powerfully muscled thighs that gave it a low center of gravity and tremendous stability, unlike the more slender-legged modern ratites like ostriches. Although initially thought to be a fearsome carnivore due to its massive beak, paleontologists now believe Bullockornis used its powerful jaw to crack nuts and crush tough vegetation. This bizarre duck relative exemplifies convergent evolution, where distantly related animals evolve similar body forms to fill similar ecological niches – in this case, developing an ostrich-like body despite being more closely related to ducks.

Stephens Island Wren: The Bird Exterminated by a Single Cat

The Stephens Island Wren (Traversia lyalli) represents one of evolution’s most unusual experiments – a completely flightless wren with underdeveloped wings, strong legs, and a short tail that scurried mouse-like through the underbrush of its tiny island home. Unlike the other massive birds on this list, this wren was tiny, weighing only about 1.3 ounces, but what makes its story truly remarkable is the nature of its extinction. The species was discovered and driven to extinction in 1894 by a single lighthouse keeper’s cat named Tibbles, who brought home numerous specimens before scientists even knew the species existed. Recent research suggests multiple feral cats may have contributed to its demise, but the basic story remains one of the most rapid documented extinctions in history. This bird evolved in isolation on a small island (Stephens Island, New Zealand) with no mammalian predators, losing its ability to fly – a successful adaptation until human settlement introduced cats, demonstrating how quickly specialized island species can disappear when new predators arrive.

Dodo: More Than Just an Evolutionary Punchline

While often caricatured as a symbol of evolutionary failure, the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) of Mauritius was actually a highly specialized bird perfectly adapted to its island environment before human arrival in the late 16th century. Recent scientific studies have revealed the Dodo was not the fat, awkward bird of popular imagination, but rather a lean, adaptable creature with a much more sophisticated sensory system than previously believed. CT scans of rare Dodo skulls show the bird had an enlarged olfactory bulb and brain regions dedicated to smell, suggesting it navigated its environment primarily through scent – an unusual adaptation for birds, which typically rely on vision. Perhaps most surprising was the discovery that Dodo birds had unusually large eyes for their size, suggesting excellent vision despite their ground-dwelling lifestyle, possibly for finding food in the dim light of dense forests. The Dodo’s extinction within less than a century of human discovery represents not an evolutionary dead-end, but rather the vulnerability of even well-adapted species to new threats like hunting, introduced predators, and habitat destruction.

These ten extraordinary extinct birds demonstrate that avian evolution has produced creatures every bit as strange and remarkable as dinosaurs. From the massive Elephant Bird to the tiny Stephens Island Wren, each represents a unique evolutionary experiment – adaptations to specific environmental conditions that produced body plans and behaviors unlike anything alive today. Their stories remind us that bird evolution is not a simple linear progression from dinosaur to modern bird, but rather a complex branching pattern that has explored countless variations on the avian form. The extinction of these remarkable species also serves as a sobering reminder of how quickly unique evolutionary lineages can disappear, particularly when confronted with human activity. By studying these lost birds, scientists continue to gain insights into evolutionary processes, ecological relationships, and the delicate balance that sustains biodiversity – lessons that remain critically important as we work to protect the remarkable birds that still share our world today.