Imagine a world where birds stood taller than humans, with massive beaks designed not for chirping pleasant melodies but for tearing flesh from bone. This wasn’t a fictional landscape from a fantasy novel but Earth during the Cenozoic era, following the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs. For nearly 60 million years, from about 62 to 2.5 million years ago, these magnificent and fearsome creatures known as terror birds (Phorusrhacidae) dominated terrestrial ecosystems as apex predators. Unlike today’s birds that often represent symbols of grace and freedom, terror birds embodied power and predatory excellence in a world vastly different from our own. Their reign spanned epochs of dramatic planetary change, from the recovery after the dinosaur extinction through the rise of mammalian megafauna. Let’s journey back to explore what Earth looked like when these remarkable avian predators ruled the land.

The Rise of Terror Birds After Dinosaur Extinction

When the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event wiped out non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago, it created ecological vacancies that survivors would eventually fill. Terror birds emerged in South America during the early Paleocene, evolving from smaller flying ancestors into flightless predators. Their rise coincided with a period when South America existed as an island continent, isolated from other landmasses due to continental drift. This isolation created a unique evolutionary laboratory where terror birds could evolve without competition from predatory mammals that dominated other continents. For millions of years, they diversified into numerous species ranging from moderately-sized hunters to giants standing over 10 feet tall. Their evolutionary success demonstrates nature’s remarkable ability to fill ecological niches, as these avian predators effectively replaced the role of large theropod dinosaurs in their isolated realm.

The Unique Geography of Terror Bird Territories

During the reign of terror birds, Earth’s geography looked dramatically different from the modern configuration of continents we recognize today. South America, where terror birds first evolved and reached their greatest diversity, existed as an island continent for much of the Cenozoic era. This isolation began around 100 million years ago when South America separated from Africa and continued until about 3 million years ago when the Isthmus of Panama formed, connecting it to North America. The continent drifted slowly westward, creating the perfect isolated laboratory for unique evolutionary developments. The South American landscape featured vast grasslands, woodlands, and subtropical forests rather than the dense rainforests that would later characterize much of the continent. When terror birds eventually expanded their range into North America during the Great American Interchange, they encountered unfamiliar competitors and prey animals, leading to new evolutionary pressures on these formidable predators.

Climate and Environmental Conditions

The climate during the terror birds’ 60-million-year reign underwent dramatic transformations that shaped their evolution and distribution. When they first appeared in the Paleocene, the world was recovering from the asteroid impact that ended the Cretaceous period, but global temperatures remained relatively warm. The subsequent Eocene epoch saw some of the warmest global temperatures of the Cenozoic era, with subtropical conditions extending much farther north and south than today. A significant cooling trend began around 34 million years ago during the Eocene-Oligocene transition, leading to more open habitats as forests gave way to grasslands in many regions. These environmental shifts from forests to more open savannas likely benefited terror birds, whose long legs made them formidable pursuit predators in open terrain. The changing climate and habitat conditions drove adaptations in terror bird species, with different lineages specializing for different environmental niches throughout their evolutionary history.

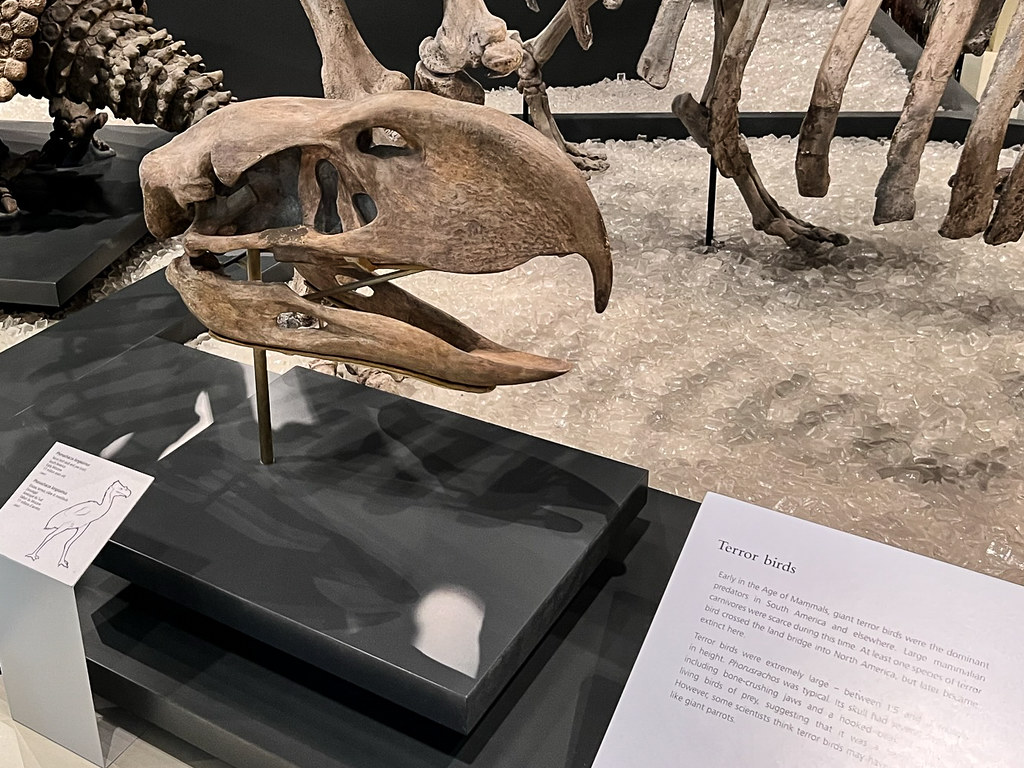

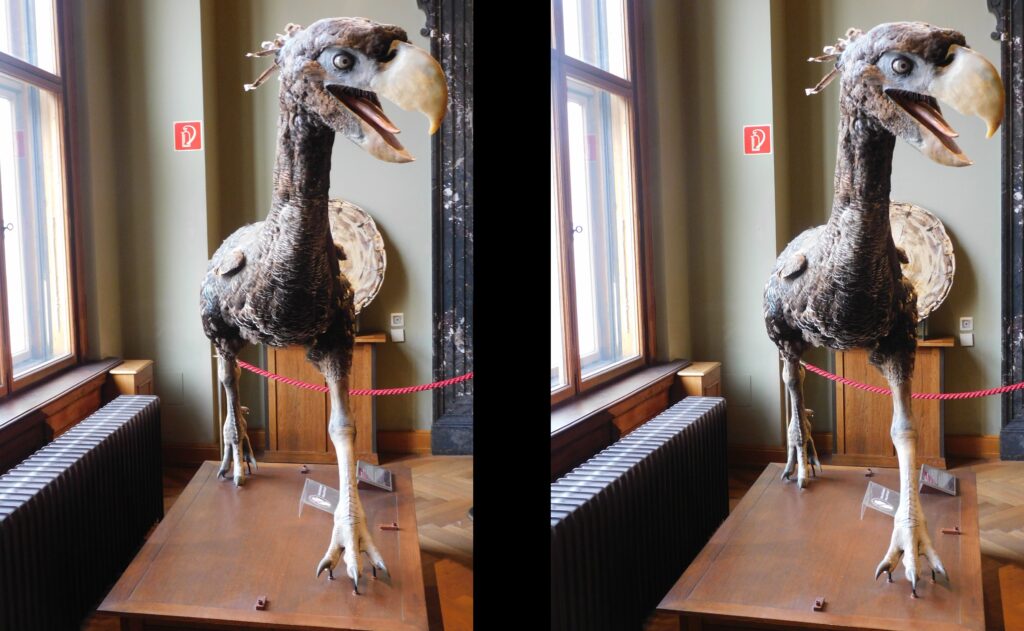

Terror Bird Anatomy and Appearance

Terror birds represented one of evolution’s most remarkable experiments in avian design, with adaptations that made them formidable predators. Standing between 3 and 10 feet tall depending on the species, their most distinctive feature was their enormous skull, which could reach nearly two feet in length in the largest species. Unlike modern birds of prey that use curved beaks to tear flesh, terror birds possessed deep, axe-like beaks with hooked tips that could deliver powerful, hatchet-like strikes to kill prey. Their skulls featured reinforced bone structures that could withstand the tremendous forces generated when striking prey. Despite their size, terror birds retained the hollow bones characteristic of avian species, balancing the need for strength with the lightweight construction that characterizes birds. Their powerful legs, ending in sharp talons rather than the grasping feet of raptors, allowed them to reach speeds estimated at 30 miles per hour—making them among the fastest predators of their time.

The Largest Terror Bird Species: Titanis and Kelenken

Among the most imposing terror birds to ever stalk the ancient landscapes were Titanis walleri and Kelenken guillermoi, giants that represent the apex of terror bird evolution. Titanis, the last known terror bird genus, stood approximately 8 feet tall and weighed around 330 pounds, with fossilized remains found in both North and South America, demonstrating how these predators expanded their range after the formation of the Panama land bridge. Kelenken, discovered in Argentina in 2006, possessed the largest known bird skull ever found, measuring an astonishing 28 inches in length, with a fearsome hooked beak designed for dispatching prey with devastating efficiency. These mega-predators lived during different periods—Kelenken during the Middle Miocene (about 15 million years ago) and Titanis persisting until about 2.5 million years ago as one of the last of their kind. The sheer size of these creatures made them capable of hunting prey that would be inaccessible to most modern birds, placing them firmly at the top of their respective food chains and making them true ecological equivalents to the theropod dinosaurs that had vanished millions of years earlier.

Hunting Techniques and Predatory Behavior

Terror birds employed hunting strategies unlike any bird alive today, combining elements of both avian and mammalian predatory techniques. Rather than swooping from above like raptors, these flightless hunters were pursuit predators that used their powerful legs to chase down prey across open grasslands. Once within striking distance, they would deploy their massive heads as precision weapons, using powerful downward strikes with their axe-like beaks to deliver fatal blows to the skull or spine of their prey. Biomechanical studies of terror bird skulls suggest they may have employed a “hold and shake” technique similar to modern birds of prey, using their strong neck muscles to manipulate captured prey. Some species likely specialized in different hunting strategies, with the larger forms tackling substantial prey while smaller species hunted more nimble animals or scavenged opportunistically. Their hunting behavior would have made them distinctive and terrifying figures on the ancient landscape, as they stalked the grasslands and woodland edges with their heads held high, scanning for potential prey with binocular vision unusual among modern birds.

The Ecosystem: Prey Animals and Competitors

The world of terror birds featured a diverse cast of potential prey animals that would seem both familiar and strange to modern observers. In South America, early hoofed mammals called litopterns and notoungulates filled ecological niches similar to today’s horses and antelopes, providing abundant hunting opportunities for terror birds. Smaller mammals including prehistoric rodents, armadillo-like creatures, and marsupials also populated these landscapes, offering prey options for the smaller terror bird species. The absence of large placental carnivores in South America for much of this period meant terror birds faced limited competition, with their main rivals being large sebecid crocodilians and sparassodont marsupials—predatory mammals distantly related to modern marsupials like opossums. When terror birds expanded into North America, they encountered a very different competitive landscape populated by established carnivores like saber-toothed cats, bone-crushing dogs, and other mammalian predators. This increased competition may explain why terror birds never achieved the same ecological dominance in North America that they enjoyed in their native southern continent.

Terror Birds in South American Isolation

South America’s lengthy period of isolation created the perfect conditions for terror birds to evolve and diversify without competition from placental mammal predators that dominated other continents. This island continent remained separated from other landmasses for over 60 million years after the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana, effectively serving as an evolutionary laboratory. Within this isolated environment, terror birds diversified into numerous species occupying various ecological niches, from forest-dwelling forms to open plain specialists. The absence of cats, dogs, and other placental carnivores meant terror birds could expand into apex predator roles normally filled by mammals elsewhere on the planet. This isolation also allowed for the evolution of other unique South American fauna that would have been familiar sights alongside terror birds, including giant ground sloths, glyptodonts (car-sized armadillo relatives), and the bizarre macraucheniids with their elephant-like trunks. Together, these animals created an ecosystem without parallel elsewhere on Earth, demonstrating how geographic isolation can drive evolutionary divergence.

The Great American Interchange

Approximately 3 million years ago, a momentous geological event transformed the world of terror birds forever: the formation of the Isthmus of Panama. This narrow land bridge connected the long-isolated South American continent with North America, initiating what paleontologists call the Great American Interchange—a massive migration of species between the two previously separated landmasses. Terror birds were among the southern species that ventured northward, with Titanis walleri establishing itself in what is now the southeastern United States. While this expansion represented a new opportunity for terror birds, it also brought them into direct competition with established North American predators like big cats and canids. Simultaneously, North American mammals moved southward, introducing new competitors and prey species to the South American ecosystems where terror birds had evolved. This biological exchange fundamentally altered the ecological dynamics that had sustained terror birds for millions of years. While some terror bird species initially thrived in this new interconnected American landscape, the increased competition and changing environmental conditions would ultimately contribute to their eventual extinction.

The Plant World During Terror Bird Times

The plant communities that formed the backdrop for terror bird evolution underwent dramatic transformations throughout the Cenozoic era. When terror birds first appeared in the Paleocene, much of South America was covered in dense tropical and subtropical forests, recovering from the catastrophic events that ended the Cretaceous period. As global cooling trends intensified during the Oligocene and Miocene epochs, these forests gradually gave way to more open habitats including savannas and grasslands, particularly in southern South America. This expansion of grasslands provided ideal hunting grounds for the long-legged terror birds, who could pursue prey across open terrain. The Andean mountain range was still forming during much of this period, creating new high-altitude habitats and affecting rainfall patterns across the continent. The changing plant communities influenced the evolution of both terror birds and their prey, as animals adapted to new food sources and habitat structures. By the time terror birds reached North America, they encountered diverse plant communities including temperate forests, grasslands, and the developing scrublands of regions like Florida where Titanis fossils have been discovered.

Contemporary Megafauna in Terror Bird Habitats

The terror birds shared their world with an impressive array of megafauna that would make modern ecosystems seem depauperate by comparison. In South America, giant ground sloths reaching the size of modern elephants browsed on trees and shrubs, while tank-like glyptodonts—relatives of armadillos with heavily armored shells—grazed on grasses and low vegetation. Strange hoofed mammals called toxodonts, resembling hippo-rhino hybrids, wallowed in ancient wetlands, while macraucheniids with their strange trunk-like nasal appendages browsed across mixed habitats. When terror birds expanded into North America, they encountered mammoths, mastodons, giant beavers, and other ice age megafauna that created a very different ecological community. Across both continents, these diverse herbivores maintained the mosaic of habitats from woodlands to grasslands that terror birds hunted within. The coexistence of terror birds with these megafaunal communities created predator-prey dynamics unlike anything in modern ecosystems, with the birds potentially targeting juvenile megaherbivores or competing with other predators for access to megafaunal carcasses.

The Decline and Extinction of Terror Birds

After dominating South American ecosystems for nearly 60 million years, terror birds began a gradual decline that ultimately led to their extinction around 2.5 million years ago. Several interconnected factors likely contributed to their disappearance from Earth’s landscapes. The Great American Interchange introduced new mammalian competitors from North America, including efficient pack hunters like wolves and large solitary predators like jaguars, creating intense competition for prey resources. Simultaneously, changing climate conditions during the Pliocene and early Pleistocene epochs altered habitat distribution, potentially reducing the open terrain where terror birds excelled as pursuit predators. Some paleontologists suggest that the introduction of novel diseases carried by North American mammals might have further stressed terror bird populations already coping with ecological pressures. The last known terror bird, Titanis walleri, persisted in Florida until approximately 2.5 million years ago—a time when global cooling was intensifying and the first major ice ages of the Pleistocene were beginning. Their extinction marked the end of one of evolution’s most remarkable experiments in avian predator design, closing a chapter in Earth’s history that had lasted for tens of millions of years.

Modern Birds: The Terror Birds’ Distant Cousins

While terror birds vanished millions of years ago, their legacy continues through their distant relatives in the modern avian world. Today’s seriemas, medium-sized birds native to South America, represent the closest living relatives to the mighty phorusrhacids. Standing about 3 feet tall, these long-legged birds share several anatomical features with their formidable ancestors, including a preference for terrestrial lifestyles and predatory habits, though on a much smaller scale. Modern seriemas hunt small vertebrates and insects, occasionally using a similar technique of grabbing prey and smashing it against the ground. Beyond seriemas, the terror bird lineage belongs to a broader group that includes modern falcons, parrots, and songbirds—a surprising connection between some of today’s most familiar birds and the ancient giants. The evolutionary transition from terror birds to these modern forms underscores the remarkable adaptability of the avian lineage, which has produced everything from tiny hummingbirds to the massive extinct terror birds, demonstrating the evolutionary plasticity that has allowed birds to persist through multiple extinction events and continue thriving in today’s world.

The world of terror birds represents a fascinating chapter in Earth’s history—a time when avian predators, rather than mammals, dominated terrestrial ecosystems across an isolated continent. Their story illustrates the profound impact of geological processes like continental drift on evolutionary trajectories, as South America’s isolation created the conditions for these remarkable creatures to evolve and thrive. As we piece together the world they inhabited through fossil evidence and geological records, we gain insight into not just these magnificent predators, but the dynamic nature of Earth’s ecosystems through deep time. Though terror birds no longer stalk Earth’s landscapes, their evolutionary story remains a testament to nature’s boundless creativity and the remarkable diversity of forms that have called our planet home across the vast expanse of geological time.