Deep within the prehistoric landscapes of what would become North America, a terrifying predator stalked its prey with the calculated precision of a modern-day hawk and the ferocity of a movie monster. Standing nearly 10 feet tall and stretching up to 40 feet in length, Deinonychus’s larger cousin Utahraptor combined massive size with deadly hunting capabilities that rival our most dramatic imaginings of prehistoric predators. Recent paleontological discoveries have revealed that despite its imposing stature, this feathered giant employed hunting techniques remarkably similar to those of its smaller, more famous relative, the Velociraptor. The evidence of feathers, pack hunting behavior, and specialized killing tools presents a picture far more nuanced and terrifying than the simplified versions often portrayed in popular media. This magnificent predator represents one of the most fascinating examples of evolution’s capacity to create efficient killing machines, wrapped in a package that blended avian characteristics with reptilian power.

The Rise of Utahraptor: A Cretaceous Apex Predator

Utahraptor roamed the early Cretaceous period approximately 125 million years ago, establishing itself as one of the dominant predators of its ecosystem. First discovered in eastern Utah in 1991, this massive dromaeosaurid dinosaur represented a game-changing find for paleontologists who had previously believed raptors were predominantly smaller predators. The discovery of Utahraptor pushed back the timeline for large dromaeosaurs by about 50 million years, challenging existing theories about raptor evolution. Unlike later, smaller raptors like Velociraptor, Utahraptor evolved its massive size early in the dromaeosaurid lineage, suggesting that gigantism was an early evolutionary strategy for these feathered predators. Its emergence coincided with the presence of large herbivorous dinosaurs in North America, indicating that Utahraptor evolved as a response to the available prey in its environment.

Anatomy of a Super-Predator

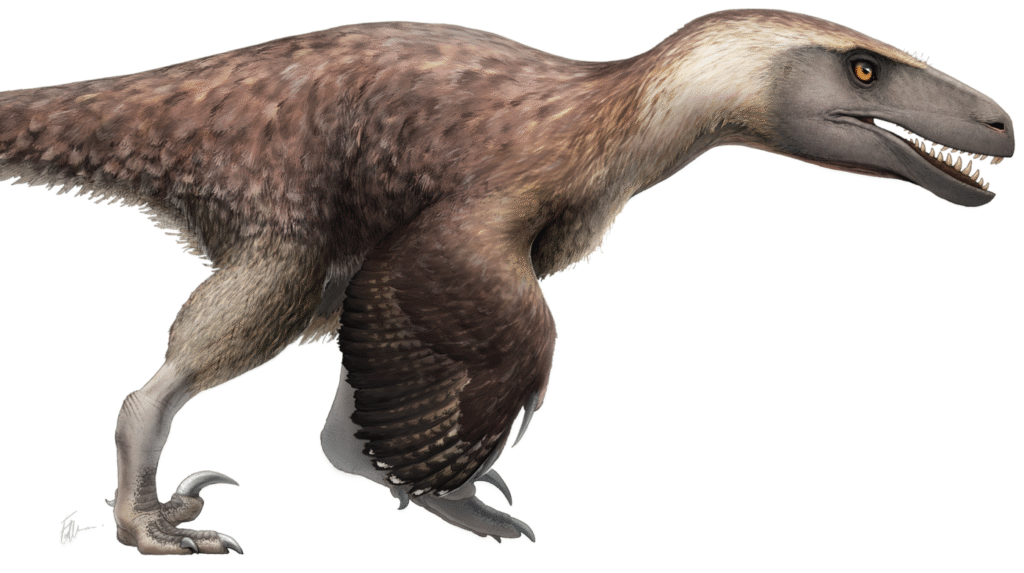

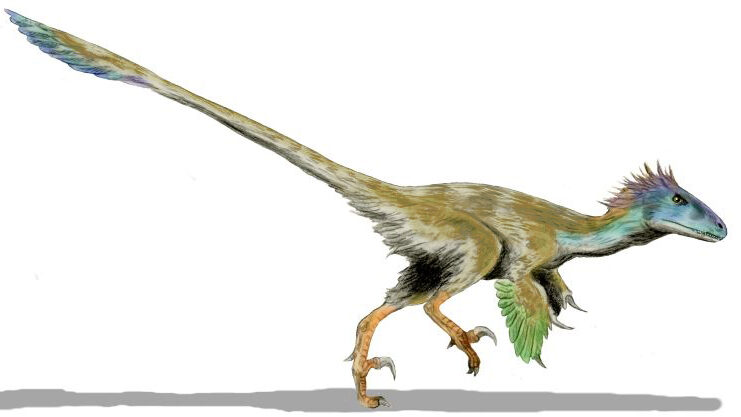

Utahraptor’s physical characteristics combined overwhelming power with precision killing tools that made it one of the most formidable predators of its time. Most distinctive was its enormous sickle-shaped claw on each second toe, measuring up to 9.5 inches in length – a lethal weapon capable of slashing deep into prey. Unlike the popular misconception of scaled, reptilian skin, Utahraptor was covered in feathers, with evidence suggesting particularly dense plumage on its arms, forming primitive wings that may have been used for display, insulation, or balance while hunting. Its skull contained dozens of serrated teeth designed for slicing through flesh rather than crushing bone, indicating a hunting style focused on inflicting deep, bleeding wounds. The predator’s robust forelimbs were equipped with three fingers ending in sharp claws, allowing it to grasp and manipulate prey with surprising dexterity for such a large animal.

The Feathered Revolution: Redefining Our Understanding

The discovery of feathers on Utahraptor and other dromaeosaurids has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaur evolution and the dinosaur-bird connection. Far from the scaly monsters depicted in earlier paleontological reconstructions, these predators possessed complex feather arrangements that likely served multiple purposes beyond insulation. The presence of symmetrical feathers on Utahraptor’s forelimbs suggests they weren’t used for flight but may have played crucial roles in mate attraction, territorial displays, or even as stabilizers during high-speed pursuits. This feathered covering has forced scientists to reconsider the appearance of many theropod dinosaurs, painting a picture of creatures that would have appeared more bird-like than previously imagined. The evolutionary relationship between Utahraptor and modern birds becomes clearer with each new fossil discovery, strengthening the consensus that birds are, in essence, living dinosaurs that survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.

The Killing Claw: Utahraptor’s Signature Weapon

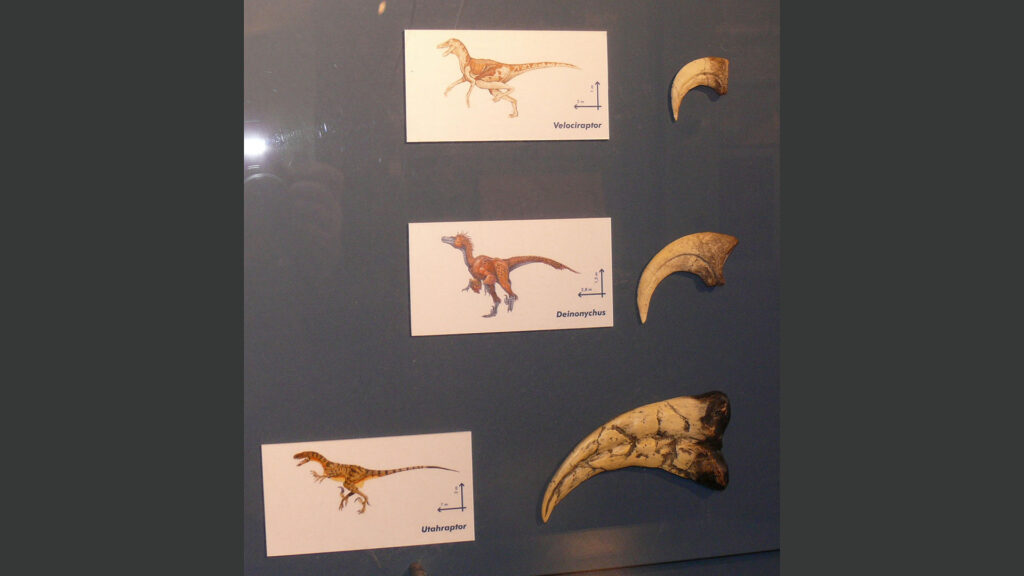

The enlarged sickle claw on Utahraptor’s second toe represents one of evolution’s most specialized killing adaptations among terrestrial predators. Unlike the claws of big cats or bears, this hypertrophied talon was kept raised off the ground during walking, preserving its sharpness for lethal strikes. Biomechanical studies suggest the claw could be deployed with tremendous force, capable of penetrating thick hide and inflicting catastrophic damage to internal organs. When hunting, Utahraptor likely used its weight and powerful hind limbs to leap onto prey, securing its position with forelimbs while the killing claws slashed repeatedly at vulnerable areas. This specialized weapon allowed Utahraptor to take down prey much larger than itself, including massive herbivores that might otherwise have been protected by their size alone. The claw’s curvature ensured that once embedded in flesh, it would be difficult to remove without causing additional trauma, making even a single strike potentially fatal.

Pack Hunting: Strength in Numbers

Perhaps most terrifying about Utahraptor was evidence suggesting these massive predators may have hunted in coordinated packs, similar to modern wolves but with vastly more lethal capabilities. A remarkable fossil find in Utah revealed multiple Utahraptor individuals of different ages preserved together, providing strong evidence for social behavior and potential pack dynamics. By hunting cooperatively, a Utahraptor pack could have successfully taken down prey many times the size of an individual raptor, including massive sauropods and heavily-armored herbivores. Pack hunting would have required significant intelligence and communication abilities, suggesting these dinosaurs possessed cognitive capabilities far beyond the simplistic “reptilian brain” concept once attributed to dinosaurs. The presence of family groups within these packs indicates a complex social structure that likely included parental care, teaching of hunting skills to juveniles, and potentially defined roles during hunts based on age and experience.

Hunting Strategies: The Perfect Ambush Predator

Analysis of Utahraptor’s physical adaptations reveals a predator perfectly designed for ambush attacks rather than long-distance pursuit. Its robust build suggests tremendous explosive power but not necessarily marathon endurance, indicating a hunting style centered around surprise and overwhelming force. Utahraptor likely concealed itself using vegetation or terrain features before launching devastating attacks on unsuspecting prey from close range. Once contact was made, the predator would use its weight to unbalance larger prey while deploying its killing claws in precise, targeted strikes to vulnerable areas like the throat, belly, or flanks. The presence of binocular vision suggests excellent depth perception, crucial for timing these precision attacks and coordinating movements with pack members. This combination of stealth, power, and precision made Utahraptor a remarkably efficient predator capable of taking down animals many times its size with minimal risk to itself.

Utahraptor vs. Velociraptor: Size Isn’t Everything

While Utahraptor dwarfed its famous cousin Velociraptor in size, the two shared remarkably similar hunting adaptations and likely employed comparable predatory strategies. Velociraptor, standing roughly knee-high to a modern human, utilized the same basic toolkit: sharp teeth, grasping hands, and the signature enlarged killing claw on each foot. Both genera likely used their feathered forelimbs to maintain balance while attacking and to help control struggling prey during takedowns. The primary difference lay in their respective prey sizes, with Utahraptor capable of tackling much larger herbivores than its smaller relative. Despite popular depictions in film and media, the turkey-sized Velociraptor would have been no less deadly for its size, particularly when hunting in packs – it simply operated at a different scale than its enormous North American cousin. Both represented pinnacles of evolutionary design as predators, with Utahraptor essentially being a scaled-up version of the same successful hunting blueprint.

The Ecological Impact of a Super-Predator

Utahraptor’s presence as an apex predator would have significantly shaped the ecosystem it inhabited, influencing everything from prey behavior to plant distribution through trophic cascades. By controlling herbivore populations, these predators would have prevented overgrazing and maintained plant diversity throughout their range. The constant threat of raptor predation likely drove the evolution of defensive adaptations in contemporary herbivores, including the development of armor, herding behaviors, and increased size. Evidence suggests Utahraptor was particularly well-adapted to hunting in forested environments, indicating these ecosystems provided ideal hunting grounds where ambush tactics could be effectively employed. As one of the largest predators in its environment, Utahraptor occupied a niche similar to modern big cats, exerting top-down pressure that maintained ecological balance and biodiversity throughout the food web.

The Intelligence Factor: Brains Behind the Brawn

Recent research into dinosaur neuroanatomy suggests dromaeosaurids like Utahraptor possessed relatively large brains for their body size, with well-developed areas dedicated to sensory processing and motor coordination. This enhanced neural capacity would have supported the complex behaviors required for successful pack hunting, including communication, spatial awareness, and strategic thinking. Studies comparing raptor brain structures to modern birds indicate they likely possessed intelligence comparable to modern corvids (crows and ravens) or possibly even some primitive primates. This cognitive sophistication would have enabled Utahraptor to adapt hunting strategies to different prey and changing environmental conditions, giving them a significant advantage over less intelligent contemporaries. The enlarged cerebrum in raptor brains particularly suggests advanced problem-solving abilities that would have made them extraordinarily effective predators beyond their physical adaptations alone.

Recent Discoveries: Changing Our Understanding

Ongoing excavations at the “Utahraptor Ridge” site in eastern Utah continue to yield remarkable new insights into this prehistoric predator’s life and behavior. A massive block containing the remains of at least six Utahraptor individuals, possibly trapped in quicksand while hunting, has provided unprecedented data about their social structure and physical characteristics. New fossil evidence has confirmed the presence of quill knobs on Utahraptor’s forearms, definitively proving these predators possessed large, complex feathers similar to those of modern birds. Careful analysis of bone growth rings has revealed information about Utahraptor’s growth rate and lifespan, suggesting these animals grew rapidly in their early years before reaching sexual maturity at approximately 7-10 years of age. These discoveries continue to refine our understanding of dromaeosaurid evolution and behavior, painting an increasingly detailed picture of how these remarkable predators lived and hunted.

Utahraptor in Popular Culture: Fact versus Fiction

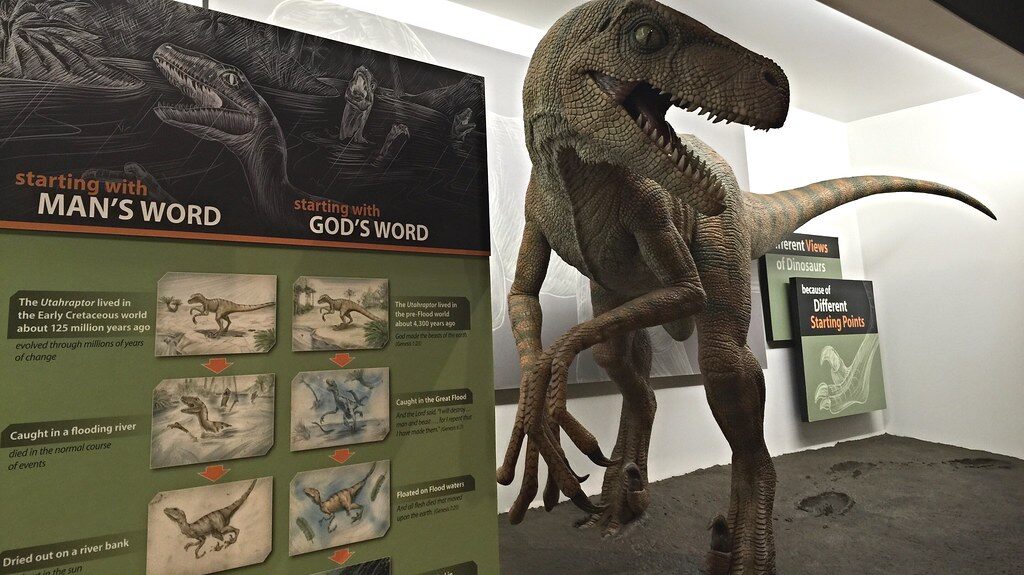

Despite its impressive credentials as one of history’s most formidable predators, Utahraptor has been relatively underrepresented in popular media compared to its smaller cousin Velociraptor. When depicted in documentaries and paleoart, Utahraptor has frequently been portrayed inaccurately, often shown without feathers or with anatomical features more consistent with other theropods. The raptors featured in the Jurassic Park franchise, while called “Velociraptors,” were actually sized closer to Utahraptor or Deinonychus, creating widespread public confusion about these distinct genera. Modern scientific illustrations now correctly depict Utahraptor as fully feathered, with plumage that may have included complex patterning and coloration used for camouflage or display. As paleontological knowledge continues to advance, representations in museums and educational media have become increasingly accurate, helping to replace outdated conceptions with scientifically informed visualizations of these remarkable predators.

Legacy of the Feathered Giants

The evolutionary innovations displayed by Utahraptor and other dromaeosaurids represent crucial stepping stones in the development of avian characteristics that would eventually lead to modern birds. The advanced feather structures, lightweight skeletal adaptations, and enhanced metabolic rates of these predators established the foundation for true flight that their descendants would later develop. Despite its extinction approximately 125 million years ago, Utahraptor’s genetic legacy continues in the more than 10,000 bird species alive today, which retain numerous anatomical and behavioral characteristics first developed in their raptor ancestors. The discovery and study of these feathered predators has fundamentally transformed our understanding of dinosaur-bird evolution, replacing the outdated notion of reptilian dinosaurs with a much more nuanced appreciation of their diversity and avian connections. In this way, Utahraptor stands not just as a fearsome prehistoric predator, but as a crucial evolutionary link that helps us understand the development of modern biodiversity.

Conclusion

As paleontological techniques continue to advance, our understanding of Utahraptor and its hunting behaviors grows increasingly sophisticated. What emerges is a picture of a supremely adapted predator that combined the raw power of a large carnivorous dinosaur with the precision and potentially the intelligence of avian hunters. Its legacy lives on not just in the fossil record but in the biological blueprint it helped establish – one that would eventually lead to the diverse avian predators that still fill our skies today. Far from being simply an oversized version of Velociraptor, Utahraptor represents a fascinating evolutionary experiment in scaling up the already successful raptor hunting model to tackle larger prey, leaving behind evidence of one of nature’s most perfect predatory designs.