During the Last Glacial Maximum approximately 20,000 years ago, North America presented a dramatically different landscape than the one we know today. Massive ice sheets covered much of the northern continent, fundamentally altering ecosystems and reshaping the distribution of wildlife. While mammals like woolly mammoths and saber-toothed cats often dominate our imagination of Ice Age fauna, the skies above this frozen wilderness were home to a remarkable diversity of avian species. These Ice Age birds not only survived but thrived in some of Earth’s most challenging conditions, developing fascinating adaptations and establishing ecological niches that offer valuable insights into evolutionary responses to climate change. From massive predatory birds that hunted megafauna to hardy arctic specialists that endured brutal conditions, the aerial inhabitants of glacial North America represent a captivating chapter in our planet’s biological history.

The Geological Canvas: North America During the Last Glacial Period

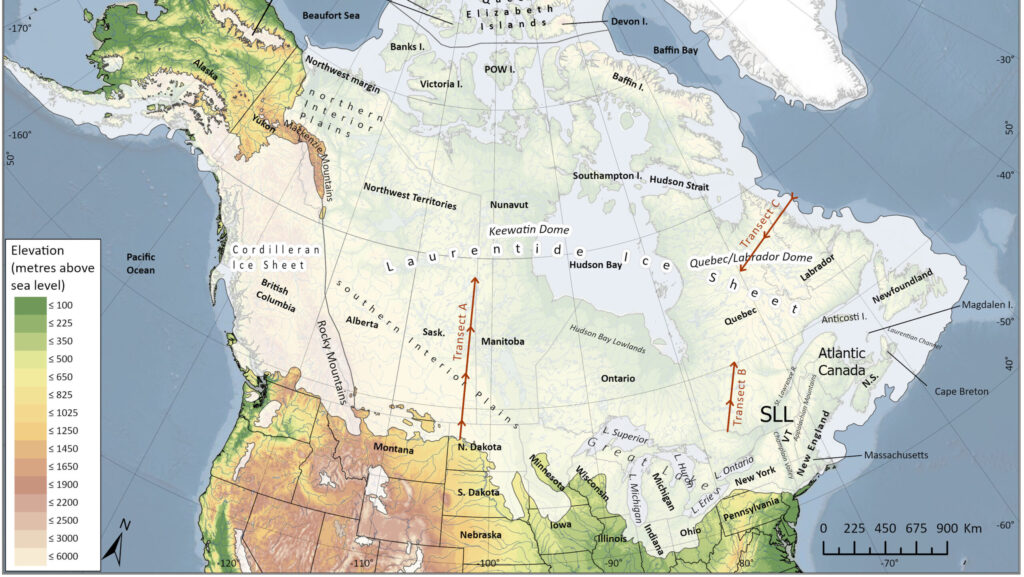

Between 110,000 and 11,700 years ago, North America experienced the Wisconsin glaciation, the most recent major glacial period that dramatically transformed the continent. At its peak around 20,000 years ago, massive ice sheets up to two miles thick covered nearly all of Canada and extended into the northern United States, creating a landscape of stark beauty and ecological extremes. South of these ice sheets stretched a mosaic of habitats including tundra, boreal forests, grasslands, and unique environments that have no modern analogs. Temperatures averaged 5-10°C colder than today, with even more dramatic cooling in northern regions. This geological and climatic reconfiguration created ecological pressures that drove unique adaptations and distributions among North America’s Ice Age birds, essentially turning the continent into a laboratory for evolutionary responses to extreme conditions.

Teratorns: The Mighty Hunters of Ancient Skies

Among the most impressive avian predators of Ice Age North America were the teratorns, massive birds with wingspans reaching up to 12 feet in the case of Teratornis merriami. These aerial giants belonged to the family Teratornithidae and combined features of both condors and storks, though recent evidence suggests they were more closely related to New World vultures. Unlike modern vultures, teratorns possessed strong feet and powerful beaks that enabled them to hunt live prey rather than merely scavenging. They likely soared above the Pleistocene landscapes of what is now California, Nevada, Florida, and Mexico, using their exceptional vision to spot small mammals, which they would seize and consume whole. The largest species, Teratornis incredibilis, may have possessed a wingspan approaching 16 feet, making it one of the largest flying birds in Earth’s history before its extinction at the end of the Pleistocene.

Titanis: The Terror Bird’s Last Stand

Though not capable of flight, no discussion of formidable Ice Age avians would be complete without mentioning Titanis walleri, North America’s only known terror bird. Standing over 8 feet tall with a massive hooked beak designed for tearing flesh, this flightless predator migrated into North America from South America during the Great American Interchange approximately 2.5 million years ago and survived until around 1.8 million years ago. Fossil evidence from Florida and Texas suggests these imposing birds were apex predators that could run at speeds approaching 40 mph, chasing down prey with their powerful legs before delivering killing blows with their axe-like beaks. Unlike their South American relatives that went extinct earlier, Titanis persisted into the early phases of North America’s Ice Age before disappearing, possibly due to competition with newly evolved mammalian carnivores or changing environmental conditions that disrupted their ecological niche.

California Condors: Ice Age Survivors

The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus), which narrowly escaped extinction in modern times, was once widespread across Ice Age North America, with fossil evidence suggesting a range extending from New York to California. During the Pleistocene, these massive scavengers with 9.5-foot wingspans played a crucial ecological role by cleaning up carcasses of megafauna including mammoths, ground sloths, and bison. Their robust bills evolved specifically to tear through the tough hides of large mammals, allowing them to access nutritious tissue that other scavengers couldn’t reach. Unlike many Pleistocene species, California condors managed to survive the end-of-Ice-Age extinction event that claimed most of North America’s megafauna, though their range contracted significantly as their primary food sources disappeared. Their persistence represents a remarkable case of partial adaptation to post-glacial conditions, making them living relics of the Ice Age that continue to soar above western landscapes.

Giant Eagles and Hawks: Aerial Predators of the Pleistocene

Ice Age North America hosted several species of eagles and hawks that dwarfed their modern counterparts in size and hunting capability. Woodward’s eagle (Amplibuteo woodwardi), discovered in California’s Rancho La Brea tar pits, possessed a wingspan estimated at 9 feet and likely specialized in hunting medium-sized mammals in open grasslands. The extinct giant hawk Buteogallus daggetti was approximately 30% larger than today’s red-tailed hawks and possessed especially powerful talons for capturing prey. These raptors evolved in ecosystems teeming with potential prey, from abundant waterfowl to small mammals that flourished in Ice Age grasslands and forests. Their hunting strategies likely involved soaring high above Pleistocene landscapes, using keen vision to spot movement below before diving at speeds exceeding 150 mph to capture prey. Most of these specialized aerial predators vanished during the end-Pleistocene extinction event, as climate change and human arrival disrupted the ecosystems they depended upon.

Snowy Owls and Arctic Specialists

The iconic snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus), with its striking white plumage and remarkable cold tolerance, expanded its range significantly during the Ice Age, following the southern advance of tundra habitats across North America. Fossil evidence indicates these arctic specialists once inhabited regions as far south as Mexico during glacial maximums, when their preferred open tundra habitat extended much farther south than it does today. Snowy owls evolved specialized adaptations for polar conditions, including heavily feathered feet that act as insulation against icy surfaces and remarkable metabolic efficiency that allows them to survive extreme cold. Their primary prey during the Ice Age would have included lemmings and other small mammals that thrived in the expanded tundra ecosystems. Unlike many Ice Age specialists, snowy owls successfully adapted to post-glacial conditions by retreating northward with their preferred habitat, demonstrating evolutionary flexibility that ensured their survival while many contemporary species perished.

La Brea’s Avian Treasures: Insights from Tar Pit Fossils

The La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles have preserved one of the world’s richest collections of Ice Age avian fossils, with over 120,000 bird specimens representing more than 140 species dating from 50,000 to 10,000 years ago. These remarkable preservations have allowed paleontologists to reconstruct detailed aspects of Pleistocene bird communities that would otherwise remain unknown. Among the most abundant birds in the La Brea collection are golden eagles, turkey vultures, and ravens, suggesting these species played important ecological roles in Ice Age ecosystems much as they do today. The tar pits have also yielded fossils of extinct species like the La Brea stork (Ciconia maltha) and numerous raptors that vanished during the end-Pleistocene extinction event. Careful analysis of these fossils, including stable isotope studies of preserved tissues, has allowed scientists to reconstruct ancient food webs and understand how avian communities responded to the climatic fluctuations that characterized the late Pleistocene in southern California.

Giant Teratorn’s Hunting Techniques and Ecological Niche

Teratornis merriami, the best-known of the North American teratorns, employed hunting strategies unlike any bird alive today, combining elements of eagles, condors, and storks in its approach to securing prey. Biomechanical studies of its skull and neck structure suggest these birds could swallow prey as large as rabbits whole, unlike modern raptors that typically tear their food into manageable pieces. Their huge wings created efficient soaring capabilities that allowed them to patrol vast territories with minimal energy expenditure, much like modern condors. However, unlike condors, teratorns possessed strong feet capable of grasping prey, though not with the specialized killing power of eagles. Evidence suggests they occupied a unique ecological niche, feeding on small to medium-sized animals caught by surprise rather than chasing fast prey or scavenging exclusively. This specialized hunting approach may explain why teratorns could not adapt when end-Pleistocene climate change altered prey availability and distribution, leading to their extinction approximately 11,700 years ago.

Giant Condors and Vultures: The Cleanup Crew

Ice Age North America supported an impressive diversity of scavenging birds that played critical roles in recycling nutrients from the abundant megafauna that roamed the continent. Besides the still-extant California condor, now-extinct species like Breagyps clarki (with a wingspan of approximately 10 feet) and the western vulture (Coragyps occidentalis) formed an efficient cleanup crew that quickly located and processed animal remains. These scavengers possessed specialized adaptations including exceptional soaring abilities that allowed them to cover vast territories while expending minimal energy, and powerful digestive systems capable of neutralizing dangerous bacteria in decomposing carcasses. They likely established complex social hierarchies at carcass sites, with larger species dominating feeding opportunities over smaller vultures and condors. The abundance of these scavengers during the Pleistocene reflected the remarkable productivity of Ice Age ecosystems, which supported dense populations of large mammals whose remains provided reliable food sources. When most megafauna disappeared around 11,700 years ago, many of these specialized scavengers lost their primary food source and subsequently went extinct.

Passenger Pigeons: From Ice Age Origins to Historic Abundance

The passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), which became notoriously extinct in 1914 due to human overhunting, actually evolved during the Pleistocene and adapted remarkably well to the changing conditions of post-glacial North America. Genetic and fossil evidence suggests this species developed its characteristic flocking behavior and nomadic lifestyle in response to the boom-and-bust cycles of forest resources during the climatic fluctuations of the late Ice Age. As glaciers retreated and deciduous forests expanded across eastern North America, passenger pigeons exploited the newly available habitat with unprecedented success, eventually forming the largest bird populations ever recorded, with flocks numbering in the billions. Their evolutionary strategy involved overwhelming predators through sheer numbers and tracking seasonal abundance of tree nuts and fruits across vast territories. Unlike many Ice Age specialists that couldn’t adapt to warming conditions, passenger pigeons thrived in the post-glacial world, demonstrating remarkable evolutionary flexibility. Ironically, their adaptation to post-Ice Age conditions was so successful that they became the continent’s most abundant bird before falling victim to industrial-scale hunting in the 19th century.

Waterfowl Adaptations in Glacial Environments

Ice Age North America featured numerous lakes, rivers, and wetlands along the margins of glaciers and in seasonally thawed regions, creating habitat for remarkably diverse waterfowl communities that evolved specialized adaptations for cold conditions. Fossil evidence from sites across the continent reveals extinct species of ducks, geese, and swans that possessed larger body sizes than their modern relatives, following Bergmann’s rule that animals in colder climates tend to be larger to conserve heat. Many Ice Age waterfowl developed enhanced insulation through denser feathering and increased subcutaneous fat, allowing them to swim in near-freezing waters that would rapidly incapacitate less-adapted birds. Their dietary flexibility was particularly important, with many species capable of switching between plant material, invertebrates, and small vertebrates depending on seasonal availability. Some species developed specialized bill morphologies for foraging in specific glacial habitats, such as shallow meltwater ponds or along the edges of ice sheets. While many specialized forms went extinct as glaciers retreated, others proved adaptable enough to evolve into the diverse waterfowl species that populate North America today.

Climate Change and Avian Migration Patterns

The dramatic climate fluctuations of the late Pleistocene profoundly influenced the development of bird migration patterns that persist in modified form today. As glaciers advanced and retreated multiple times during the Ice Age, birds developed behavioral adaptations to track habitable conditions and food resources across changing landscapes. Many species established north-south migration routes that followed the seasonal retreat and advance of glacial conditions, with breeding territories expanding northward during summer thaws and concentrating southward during winter freezes. Fossil evidence from different latitudes suggests that species now considered permanent residents in particular regions were often migratory during the Ice Age, as seasonal extremes made year-round occupation of northern territories impossible. The evolution of these complex migratory behaviors involved remarkable navigational abilities, including celestial orientation, magnetic field sensitivity, and landscape memory that allowed birds to travel thousands of miles between seasonal habitats. As North America warmed following the end of the Pleistocene, many species adjusted their migratory routes or became sedentary in newly hospitable regions, while others maintained traditional pathways that had proven successful for thousands of generations.

The End-Pleistocene Extinction Event and Avian Survivors

Approximately 11,700 years ago, North America experienced a profound extinction event that eliminated roughly 70% of its large mammal species, yet birds showed a notably different pattern of extinction and survival. While specialized avian megafauna like teratorns and certain eagles disappeared, the majority of bird species successfully navigated the challenging transition from glacial to interglacial conditions. This differential survival rate likely reflects several advantages birds possessed, including mobility that allowed rapid range shifts in response to changing habitats, dietary flexibility that permitted adaptation to new food resources, and relatively efficient metabolisms that required less food than similarly-sized mammals. The bird species that struggled most were those with highly specialized feeding strategies dependent on megafauna, such as certain vultures and condors that had evolved to process large carcasses. Genetic studies of surviving lineages suggest many experienced population bottlenecks during this transition period but managed to recover as new ecological opportunities emerged in the warming landscape. The survivors of this extinction filter went on to diversify into the bird communities that populate North America today, carrying adaptations forged during the Ice Age in their genes and behaviors.

Modern Discoveries and Research Methods

Our understanding of Ice Age avian communities has been revolutionized in recent decades by advances in research technologies and methodologies. DNA analysis of preserved tissues from tar pits and permafrost has allowed scientists to reconstruct evolutionary relationships between extinct and modern species with unprecedented precision, revealing surprising connections and divergences. High-resolution CT scanning of fossils has enabled detailed studies of flight mechanics and feeding adaptations without damaging irreplaceable specimens. Stable isotope analysis of preserved feathers and bones has provided insights into diets and migration patterns of Ice Age birds by examining chemical signatures that reflect what they ate and where they lived. Climate modeling paired with ecological niche analysis has allowed researchers to create detailed reconstructions of potential habitats and distributions of various species throughout the climate fluctuations of the late Pleistocene. These technological advances continue to yield new discoveries, with several previously unknown Ice Age bird species identified in the past decade alone, suggesting our understanding of North America’s glacial avifauna remains incomplete despite significant progress.

Conclusion

The birds that soared above Ice Age North America represent a remarkable chapter in evolutionary history, demonstrating nature’s resilience and adaptability in the face of extreme environmental challenges. From massive teratorns that hunted across Pleistocene plains to hardy arctic specialists that thrived in glacial conditions, these avian species developed specialized adaptations that allowed them to exploit the unique ecological niches of a world dramatically different from our own. While many specialized forms disappeared during the warming transition at the end of the Pleistocene, others successfully adapted to changing conditions, contributing genetic and behavioral traits to modern bird populations. By studying these ancient avian communities, scientists gain valuable insights into how birds respond to climate change—lessons that take on renewed relevance as today’s bird populations face anthropogenic warming at rates far exceeding those experienced during the natural conclusion of the Ice Age. The story of North America’s glacial birds reminds us that our current avian diversity represents just the latest chapter in an ongoing evolutionary narrative shaped by environmental change and biological resilience.