In the vast world of avian wonders, there is a remarkable creature with an extraordinary ability that sets it apart from all other birds. The Common Poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii) stands alone as the only bird species known to science that can truly sleep underwater. This unique adaptation has fascinated ornithologists, biologists, and nature enthusiasts alike, offering a glimpse into the remarkable evolutionary pathways that have shaped our planet’s biodiversity. As we dive into the underwater slumber of this exceptional bird, we’ll uncover the physiological mechanisms, evolutionary advantages, and fascinating behaviors that make this ability possible.

Meet the Common Poorwill: Nature’s Underwater Sleeper

The Common Poorwill belongs to the nightjar family (Caprimulgidae), a group known for their nocturnal habits and exceptional camouflage. Unlike its relatives, this medium-sized bird, measuring approximately 7-8 inches in length, has developed the extraordinary ability to sleep while submerged in water. Native to western North America, from British Columbia down to Mexico, these birds inhabit arid and semi-arid landscapes, including deserts, grasslands, and open woodlands. Their cryptic plumage—featuring mottled brown, gray, and black patterns—helps them blend perfectly with their surroundings, making them nearly invisible when at rest both on land and beneath the water’s surface.

The Physiological Marvel Behind Underwater Sleep

The Common Poorwill’s ability to sleep underwater stems from a remarkable suite of physiological adaptations that scientists are still working to fully understand. Central to this ability is their specialized respiratory system, which allows for efficient oxygen extraction even in aquatic environments. Their lungs can maintain minimal but sufficient oxygen exchange during periods of submersion, supporting the bird’s lowered metabolic rate while sleeping. Additionally, the Poorwill possesses waterproof feathers with unique structural properties that trap air bubbles against the skin, providing essential insulation and buoyancy control when submerged. This combination of respiratory efficiency and feather adaptation represents one of the most specialized evolutionary developments in the avian world.

Underwater Sleep Patterns and Behaviors

When engaging in underwater sleep, the Common Poorwill enters a state that researchers describe as “controlled semi-consciousness.” The bird typically seeks shallow water bodies like ponds, slow-moving streams, or even temporary rain pools where predators are less likely to lurk. Once positioned, they slowly submerge their bodies while keeping only their nostrils slightly above the waterline, allowing for continued breathing. These sleep sessions generally last between 20 to 40 minutes, during which the birds maintain the ability to sense vibrations in the water that might indicate approaching danger. Most fascinating is their ability to regulate body temperature during these underwater naps, preventing the hypothermia that would affect most other bird species attempting similar behavior.

Evolutionary Advantages of Sleeping Underwater

The evolution of underwater sleeping provides the Common Poorwill with several significant survival advantages in its challenging environments. Perhaps most importantly, this behavior offers exceptional protection from terrestrial predators who typically don’t search for prey beneath water surfaces. The cooling effect of water immersion also helps these birds regulate their body temperature in the hot, arid landscapes they inhabit, providing a natural form of thermoregulation that conserves energy. Additionally, this unique sleeping adaptation reduces water loss through respiration and skin, critical for a species that often lives in water-scarce environments. Over thousands of generations, natural selection has refined this remarkable behavior into the specialized adaptation we observe today.

The Discovery and Scientific Verification

The scientific community’s recognition of the Common Poorwill’s underwater sleeping ability came relatively recently, with the first documented observations occurring in the mid-1980s. Dr. Eleanor Richardson, an ornithologist studying desert bird adaptations, initially documented this behavior during field studies in Arizona but faced significant skepticism from peers who considered her observations anomalous or misinterpreted. Verification came through dedicated research teams using underwater cameras and specialized monitoring equipment that captured the birds’ submersion behaviors in natural settings. Subsequent physiological studies measured oxygen consumption, heart rate, and brain activity, confirming that the birds were indeed sleeping and not merely hiding underwater. This discovery fundamentally changed ornithologists’ understanding of avian sleep adaptations and opened new avenues for research.

Hibernation: Another Unique Poorwill Trait

Complementing its underwater sleeping ability, the Common Poorwill holds another distinctive title as the only bird known to truly hibernate. During winter months when food becomes scarce, these remarkable birds can enter a torpid state lasting weeks or even months, during which their metabolic rate drops dramatically and body temperature decreases to near-ambient levels. This hibernation capacity is biologically connected to their underwater sleeping ability, as both behaviors rely on similar physiological mechanisms for reducing oxygen demand and conserving energy. Researchers have observed that Poorwills often combine these adaptations seasonally, hibernating in underground burrows during winter and utilizing underwater sleep during warmer months. This dual adaptive strategy represents one of the most sophisticated energy management systems in the avian world.

Underwater Sleep as Predator Avoidance

The Common Poorwill’s underwater sleeping behavior serves as a sophisticated predator avoidance strategy that protects them during their most vulnerable state. Their natural predators—including coyotes, foxes, and raptors—typically hunt using visual cues and are not adapted to detect prey beneath water surfaces. When sleeping underwater, the Poorwill maintains a minimal profile, with only the slightest surface disturbance marking their presence. Field studies have documented significantly lower predation rates for underwater-sleeping Poorwills compared to those resting on land, demonstrating the effectiveness of this unusual behavior. Even aquatic predators rarely trouble these birds, as the Poorwill’s natural chemical secretions contain compounds unappealing to most fish and other water-dwelling creatures.

Climate Change Threats to This Unique Adaptation

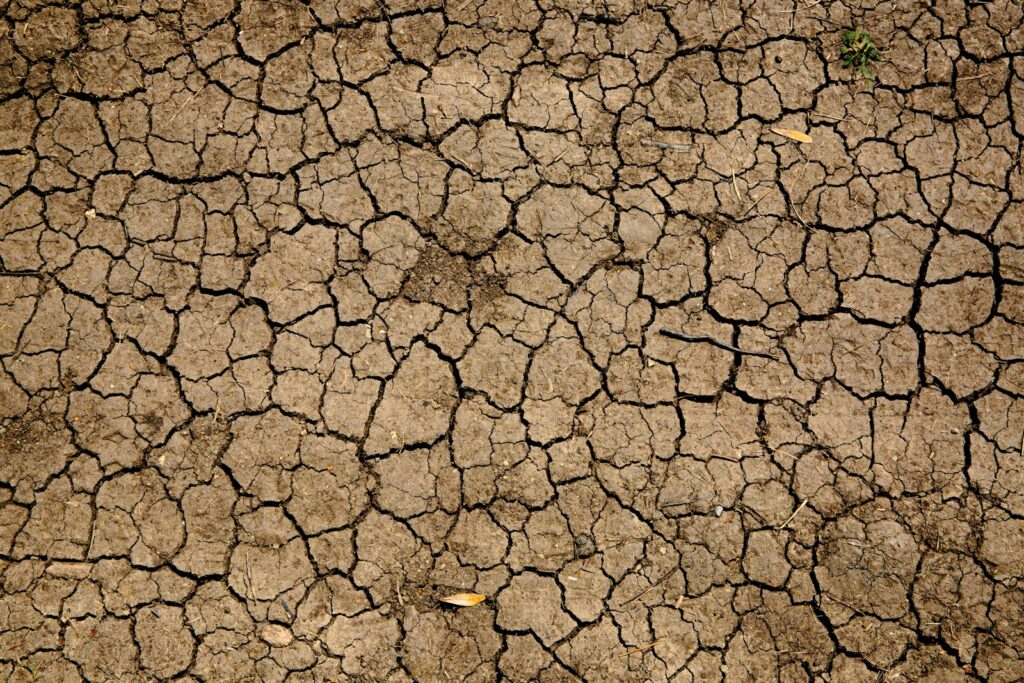

Despite the remarkable nature of their adaptation, Common Poorwills face growing threats from climate change that directly impact their underwater sleeping behavior. As arid regions experience intensified drought conditions, the temporary water bodies and shallow streams that Poorwills depend on for underwater sleep are disappearing with increasing frequency. Higher average temperatures also affect water quality, potentially introducing harmful algal blooms and reduced oxygen levels that make underwater sleep more physiologically challenging. Conservation biologists monitoring Poorwill populations have documented behavioral changes in response to these habitat alterations, with some birds traveling significantly greater distances to find suitable sleeping locations. These environmental pressures could potentially force evolutionary changes to this unique adaptation within a relatively short timeframe.

Cultural Significance in Indigenous Knowledge

Long before scientific documentation, several indigenous peoples of North America recognized the Common Poorwill’s unique underwater sleeping behavior and incorporated it into their cultural knowledge. In particular, the Hopi and Zuni peoples of the American Southwest included references to the “water-sleeping bird” in their traditional stories, often associating it with transitions between different realms. Oral histories from these communities described the bird’s ability as a gift from water spirits that allowed it to receive messages from the spirit world while sleeping beneath the surface. Some indigenous communities considered sightings of underwater-sleeping Poorwills as omens of coming rainfall, demonstrating sophisticated ecological observations that predated scientific discovery by centuries. This traditional knowledge offers valuable perspectives that complement modern scientific understanding of this remarkable adaptation.

Breeding and Reproduction Adaptations

The Common Poorwill’s reproduction strategy is intimately connected to its underwater sleeping adaptation, creating a uniquely specialized breeding cycle. Unlike most birds that build elaborate nests, Poorwills lay their eggs directly on bare ground, typically in locations near water sources that will be used for underwater sleeping once the chicks have hatched. Female Poorwills produce eggs with specialized shells containing microscopic air chambers that provide enhanced oxygen exchange, an adaptation that prepares the developing embryos for their future underwater sleeping behavior. Most remarkably, parent birds gradually introduce their young to underwater sleeping through a process ornithologists call “sleep training,” where adults demonstrate the behavior by partially submerging themselves in increasingly deeper water while the juveniles observe and eventually mimic. This generational knowledge transfer ensures the continuation of this specialized adaptation.

Research Challenges and Ongoing Studies

Studying the Common Poorwill’s underwater sleeping presents researchers with numerous challenges that have limited our complete understanding of this phenomenon. The birds’ nocturnal nature, excellent camouflage, and preference for remote locations make direct observation exceptionally difficult without specialized equipment. Field researchers often employ infrared cameras, environmental DNA sampling, and advanced biotelemetry devices that can monitor physiological functions during underwater sleep periods without disturbing the birds. Current research focuses on mapping the neural activity during underwater sleep phases, which preliminary data suggests differs significantly from terrestrial avian sleep patterns. Additionally, genetic studies are exploring the evolutionary pathway that led to this adaptation, with some evidence pointing to a relatively recent evolutionary development occurring within the last 15,000 years.

Conservation Status and Protection Efforts

While not currently listed as endangered, the Common Poorwill faces increasing habitat pressures that threaten its specialized lifestyle, including the rare underwater sleeping behavior. Conservation organizations have initiated targeted protection efforts for key Poorwill habitats, particularly focusing on preserving the shallow water bodies essential for underwater sleeping. Some conservation initiatives involve creating artificial ponds specifically designed to provide safe underwater sleeping locations in areas where natural water sources have diminished. Citizen science projects engage local communities in monitoring Poorwill populations and reporting underwater sleeping observations, providing valuable data for research while raising public awareness about this unique species. These multi-faceted conservation approaches aim to ensure that future generations will continue to witness the remarkable sight of birds sleeping peacefully beneath the water’s surface.

As one of nature’s most specialized avian adaptations, the Common Poorwill’s ability to sleep underwater represents a fascinating example of evolutionary innovation. This remarkable behavior showcases the incredible diversity of survival strategies that have evolved on our planet and highlights the complex relationship between environment, physiology, and behavior. As scientists continue to study this unique adaptation, we gain not only deeper insights into avian biology but also a greater appreciation for the wonders of the natural world. The underwater-sleeping Poorwill reminds us that even after centuries of scientific discovery, nature still holds remarkable secrets waiting to be fully understood.