Deep in the heart of North America, an extraordinary annual event unfolds high above the ground. As seasons change, a remarkable bird embarks on one of nature’s most peculiar journeys—a migration pattern that traces a massive spiral across the continent. The Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni) undertakes this incredible feat, traveling from its breeding grounds in North America to wintering territories in Argentina’s pampas grasslands. Unlike most migratory birds that follow relatively direct paths, these remarkable raptors travel in a counterclockwise spiral pattern that has fascinated ornithologists for decades. This unique migratory strategy represents one of the most distinctive and specialized movement patterns in the avian world, covering over 12,000 miles in a journey that showcases both the wonders of evolutionary adaptation and the remarkable navigational abilities of these birds.

The Spiral Migration Marvel

The Swainson’s Hawk performs what scientists call a “loop migration,” creating a giant spiral pattern that spans two continents. These birds travel south through the central United States and Mexico in the fall, continuing through Central America and along the eastern edge of the Andes Mountains to reach Argentina. What makes this journey truly remarkable is their return route—instead of retracing their steps, they fly northward along a more eastern path through central South America and up along the eastern side of Central America. This creates a massive counterclockwise loop that, when mapped, resembles a gigantic spiral stretching across the Americas. The entire round-trip journey covers approximately 12,000-14,000 miles, making it one of the longest migrations of any North American raptor species.

The Swainson’s Hawk Profile

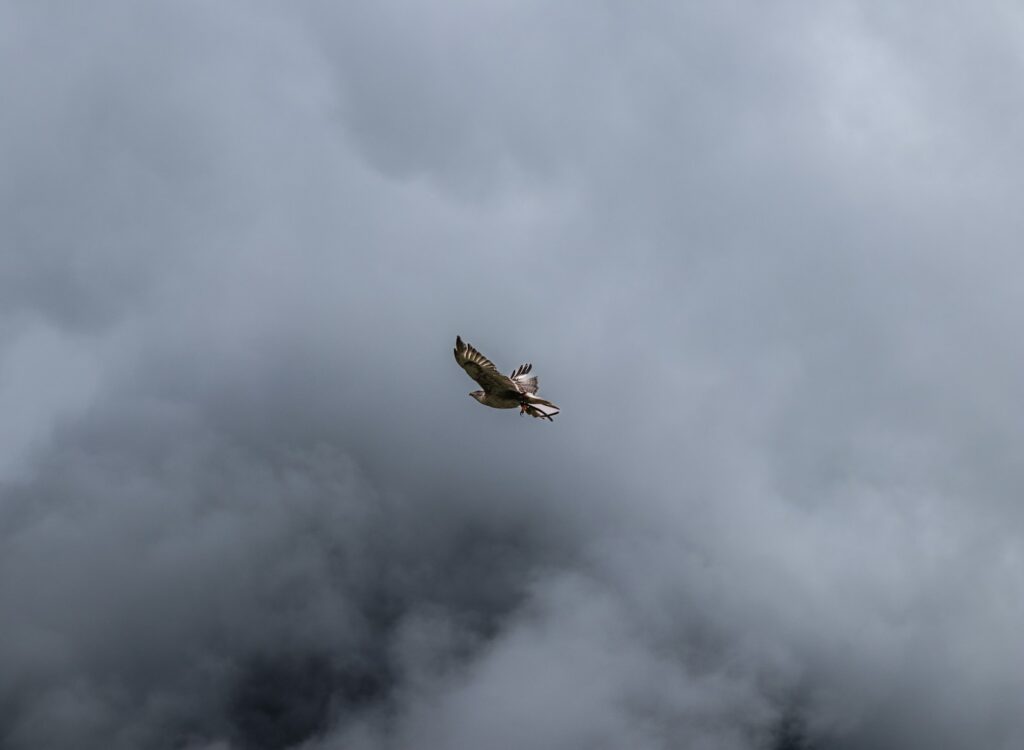

The Swainson’s Hawk is a medium-sized raptor with distinctive coloration and physical adaptations perfect for its migratory lifestyle. Adults typically weigh between 1.1 and 1.7 pounds with a wingspan reaching up to 4.5 feet, making them well-suited for long-distance soaring flight. They display remarkable plumage variation, with three main color morphs: light, rufous, and dark. The light morph features a white throat and belly contrasted with a dark bib and brown back, while the less common dark morph appears almost uniformly blackish-brown. Their relatively long, pointed wings optimize their ability to capture thermal updrafts during migration, allowing them to cover vast distances while expending minimal energy—a crucial adaptation for their extraordinary migratory journey.

The Timing of the Spiral

The spiral migration of Swainson’s Hawks follows a strict seasonal schedule dictated by breeding cycles and food availability. These birds typically arrive at their North American breeding grounds between March and April, with populations spreading across the western United States and Canada’s prairie provinces. They remain in these northern territories throughout the summer breeding season, raising their young and taking advantage of abundant rodent populations. By late August and September, as temperatures begin to cool and prey becomes scarcer, the hawks gather in large flocks—sometimes numbering thousands—and commence their southward journey. They reach their Argentine wintering grounds by early November, where they’ll remain until beginning their northward spiral in February or March, perfectly timing their movements to match resource availability across two continents.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Spiral Migration

The spiral migration pattern demonstrated by Swainson’s Hawks represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that offers several significant advantages. By taking different routes southward and northward, these birds optimize their exposure to favorable wind patterns and thermal currents that differ seasonally, significantly reducing energy expenditure during long flights. This strategic routing also allows them to follow the most abundant food resources throughout their journey, tracking insect emergences and rodent populations that fluctuate in different regions at different times. Additionally, the spiral pattern reduces competition for food resources by preventing excessive concentration of birds in any single flyway. Perhaps most fascinating is how this migration strategy allows the hawks to avoid geographical barriers like the Gulf of Mexico at their widest points, minimizing dangerous over-water crossings that could prove fatal during adverse weather conditions.

Tracking the Spiral Through Modern Technology

Our understanding of the Swainson’s Hawk’s spiral migration has been revolutionized by advancements in tracking technology over recent decades. Early studies relied primarily on bird banding, which provided limited snapshots of these birds’ movements when bands were recovered. The introduction of satellite telemetry in the 1990s transformed our knowledge, allowing researchers to attach small transmitters to individual hawks and track their precise movements in real-time across continents. More recent technological innovations include lightweight GPS tags and geolocators that can record data for multiple years, revealing previously unknown details about migration routes, stopover locations, and travel speeds. These technologies have documented hawks traveling up to 124 miles per day during peak migration and confirmed that individual birds follow remarkably similar routes year after year, suggesting an innate navigation system guiding their spiral journey.

The Mystery of Navigation

How Swainson’s Hawks navigate their precise spiral migration route remains one of ornithology’s most fascinating questions. Scientists believe these birds employ multiple navigation techniques simultaneously to maintain their course across thousands of miles. They likely possess an innate magnetic compass that allows them to sense Earth’s magnetic field, providing constant directional information regardless of weather conditions. Visual landmarks play a crucial role as well, with the hawks following major mountain ranges, rivers, and coastlines that serve as consistent geographical signposts. Research suggests they may also navigate using celestial cues, orienting themselves by the position of the sun during day flights and star patterns during nocturnal migration segments. Perhaps most remarkably, evidence indicates that experienced adults pass migration knowledge to younger birds, creating a cultural transmission of route information that persists across generations.

The Social Dynamics of Spiral Migration

Unlike many bird species that migrate individually or in small family groups, Swainson’s Hawks undertake their spiral journey in large, loosely organized flocks that create an important social dimension to their migration. During peak migration periods, observers have documented “kettles” containing hundreds or even thousands of hawks spiraling upward on thermal currents before gliding south to the next thermal. These social groupings serve critical functions beyond companionship, as they significantly enhance migration efficiency and safety. Inexperienced birds, particularly first-year juveniles making their initial migration, benefit from the navigational knowledge of older, experienced hawks that have completed the journey previously. The flock structure also improves predator detection and provides collective intelligence for locating thermal updrafts and food resources, with successful hunting behaviors quickly spreading through the group as they travel together across two continents.

Feeding Strategies During the Great Spiral

The Swainson’s Hawk demonstrates remarkable dietary flexibility during its spiral migration, adapting its feeding strategies to match available prey across diverse ecosystems. While breeding in North America, these birds primarily hunt small mammals like ground squirrels, pocket gophers, and voles that thrive in prairie environments. As they begin their southward spiral, their diet shifts dramatically to focus on insects, particularly large grasshoppers, dragonflies, and emerging populations of migratory locusts and caterpillars. This dietary adaptation is most evident during their time in Argentina, where they become almost exclusively insectivorous, following and feeding on massive outbreaks of grasshoppers and locusts that occur in the pampas grasslands. Researchers have documented how these hawks will follow insect swarms across hundreds of miles, timing their movements to coincide with peak insect emergences that provide the caloric requirements necessary for their eventual northward return.

Conservation Challenges Along the Spiral

The Swainson’s Hawk’s spiral migration exposes it to diverse conservation threats across multiple countries and ecosystems. In the 1990s, populations experienced a significant decline when thousands of hawks died in Argentina due to pesticide poisoning, particularly from monocrotophos used on agricultural fields where the birds foraged for insects. Habitat loss represents another significant challenge, as grasslands and prairies at both ends of their migration route face conversion to intensive agriculture, reducing suitable breeding and wintering habitat. Climate change poses perhaps the most complex threat, as it disrupts the synchronized timing between the hawks’ migration and the availability of their prey species, particularly insect populations that emerge based on temperature and rainfall patterns. Because their spiral route crosses multiple international boundaries, effective conservation requires coordinated efforts between the United States, Mexico, Central American nations, and Argentina to protect this remarkable migratory phenomenon.

Cultural Significance Across the Americas

The spectacular spiral migration of Swainson’s Hawks has embedded these birds in the cultural traditions of various communities along their extensive flyway. In parts of the western United States and Canada, local festivals celebrate the hawks’ spring arrival, marking the seasonal transition and historical importance of these birds to indigenous peoples who viewed their return as a sign of agricultural timing. Throughout Central America, particularly in locations where migration bottlenecks create dramatic concentrations of hawks, ecotourism has developed around migration viewing, bringing economic benefits to rural communities. In Argentina’s pampas region, the arrival of “aguiluchos langosteros” (grasshopper hawks) has traditionally been welcomed by farmers as natural pest control for locust populations that threaten crops. This shared cultural appreciation across multiple countries has helped foster international conservation efforts and public support for protecting the remarkable birds that connect continents through their spiral journey.

Similar Migration Patterns in Other Species

While the Swainson’s Hawk’s spiral migration is particularly pronounced, similar loop migration patterns appear in several other avian species, suggesting the evolutionary advantages of this strategy. The Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) populations that breed in North America often migrate along different routes in fall and spring, creating their own version of a migration loop. The Northern Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe), despite being a small songbird, performs an elliptical migration between Arctic breeding grounds and African wintering territories. Among butterflies, the Monarch (Danaus plexippus) demonstrates a multi-generational migration loop that spans multiple countries. Even within hawk species, the Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus) shows elements of loop migration, though less dramatically than its Swainson’s cousin. These parallel evolutionary developments across unrelated species highlight how spiral or loop migrations represent successful adaptations to seasonal resource availability and geographical barriers, emerging independently in multiple lineages.

Citizen Science and the Spiral

The dramatic nature of the Swainson’s Hawk’s spiral migration has made it an ideal focus for citizen science initiatives that engage the public in scientific research. Programs like HawkWatch International coordinate volunteer observers at key migration bottlenecks, collecting long-term data on hawk numbers, timing, and behavior that would be impossible for professional scientists to gather alone. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird platform enables casual birdwatchers to report Swainson’s Hawk sightings throughout the Americas, creating a comprehensive database that reveals migration timing and route variations. In Latin American countries, local conservation organizations train community monitors who track hawk movements and help protect stopover sites that are crucial for the birds’ successful migration. These citizen science efforts not only generate valuable scientific data but also build public appreciation for the hawks’ remarkable journey, creating grassroots advocacy for conservation measures across international boundaries.

The Future of the Spiral Migration

The continued existence of the Swainson’s Hawk’s spiral migration faces an uncertain future in a rapidly changing world. Climate change models predict shifting precipitation patterns that could fundamentally alter the grassland ecosystems these birds depend on at both ends of their migration. Agricultural intensification continues to transform landscapes along their route, though sustainable farming practices that reduce pesticide use offer hope for safer feeding grounds. Emerging research suggests these hawks do show some behavioral plasticity, with documented changes in migration timing and stopover locations in response to environmental conditions, indicating potential resilience to moderate changes. Conservation successes, including the international ban on monocrotophos pesticides following the Argentine poisoning events, demonstrate that coordinated conservation action can effectively address specific threats. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of this remarkable spiral migration through scientific study, our growing understanding creates opportunities for targeted conservation efforts that could ensure future generations witness this magnificent aerial spectacle connecting the Americas.

The spiral migration of the Swainson’s Hawk stands as one of nature’s most extraordinary phenomena—a continental-scale journey that connects ecosystems, cultures, and countries across the Americas. This remarkable adaptation represents the culmination of evolutionary processes that have finely tuned these birds to navigate vast distances with precision while maximizing their chances of survival. As we continue to study their journey through increasingly sophisticated tracking technologies, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for the intricate connections that bind our natural world together. The future of this magnificent spiral migration now depends largely on human choices—whether we can preserve the habitats, reduce the threats, and maintain the environmental conditions necessary for these birds to continue their ancient journey. In protecting the Swainson’s Hawk and its remarkable migration pattern, we ultimately protect a living emblem of wilderness that transcends borders and reminds us of the breathtaking complexity and resilience of life on Earth.